CHEAT SHEET

- Threatened misappropriation. An employer can seek injunctive relief before misappropriation of its trade secrets if it can prove a former employee’s intent to wrongfully acquire, use, or disclose said information.

- Prove it. To prove threatened misappropriation, an employer must demonstrate that the former employee had possession of trade secrets, more than a generalized understanding of them, and threatened through words or actions to disclose them.

- Inevitable disclosure. Depending on the jurisdiction, a former employee’s knowledge of trade secrets and the inevitability that he may use them in his new position with a competitor can be grounds for threatened misappropriation.

- What’s the secret? An injunction is more likely when the trade secrets in dispute are specific, technical, contemporary, critical to business, durable, and are capable of being remembered.

Many companies consider trade secrets the “crown jewels” of the organization. Without trade secrets, the fundamentals of their business can be compromised, as recent headlines have confirmed. But what if companies could stop trade secret theft before it happens?

The law does not require that an employer await an actual misappropriation of its trade secrets before seeking injunctive relief. Both the Uniform Trade Secrets Act (UTSA) and the Defend Trade Secrets Act (DTSA) provide that a court may enjoin “threatened” as well as “actual” misappropriation. While “misappropriation” is defined under both the UTSA and the DTSA, the word “threatened” is not. A threat is an express or implied declaration of intent to injure the person, property, or rights of another. Thus, threatened misappropriation under both the UTSA and DTSA can be understood as an express or implied declaration of intent to wrongfully acquire, use, or disclose another’s trade secret.

Inferring intent is difficult, particularly when an employee abruptly resigns to start a new business, join a competitor, or pursue another business opportunity. One rarely knows with certainty what information the departing individual is planning to take. Portable storage devices and email have only heightened this anxiety. Documents that in years past would have been packed into a searchable box or briefcase can now slip the bounds of a business with the push of a button. Non-competes, non-solicitation, and non-disclosure agreements incentivize departing individuals to resist the urge to take confidential information but they are just promises that assure nothing other than consequences for wrongdoing, which many people are willing to risk for the chance to unjustly enrich themselves. Thus, notwithstanding a departing individual’s contracts, sincere goodbyes, and assurances that all confidential and proprietary information has remained in place, the ease by which information can be removed from a business today necessitates no less than “trust but verify” suspicion.

It is rare for a person to declare his intention to misappropriate his former employer’s trade secrets. That threat must ordinarily be inferred from events, behavior, and other circumstances proximate to the employee’s resignation.

It can include the identity of the new employer, the nature of the former employee’s new job, the former employee’s candor about his future plans, the trade secrets he had access to during employment; the nature and importance of particular trade secrets at risk; the manner in which the former employee resigned, and the former employee’s handling of the former employer’s confidential information at or around the time of his resignation. What is particularly baffling, especially where suspicion of wrongdoing is palpable, but proof of actual misappropriation is absent, is understanding what facts suffice to move “suspected” misappropriation into the realm of actionable “threatened” misappropriation. Is mere knowledge of a former employer’s trade secrets coupled with taking a similar position with a direct competitor enough? Or does there need to be proof of wrongdoing or bad faith, such as after-hour downloads copied onto a flash drive or emailed to a personal email account? How much evidence suffices to obtain an injunction to prevent what is believed to be an impending misappropriation? This article seeks to explain how courts assess misappropriation and how in-house counsel can prepare for the departure of an employee who has access to the company’s “crown jewels.”

Threatened misappropriation

Judicial definitions of threatened misappropriation

Given the absence of a statutory definition, courts have sought to define threatened misappropriation both by what it is and what it is not, with due concern for the impact that a finding of threatened misappropriation could have on competition. Threatened misappropriation requires showing more than mere possession of a properly acquired trade secret. There also must be a showing that the former employee has more than a generalized knowledge of the former employer’s trade secrets. Merely suspecting or fearing injury is not enough to earn an injunction. There must be a substantial threat to the company. A trade secret will not be protected by the extraordinary remedy of an injunction on mere suspicion.

Thus, notwithstanding a departing individual’s contracts, sincere goodbyes, and assurances that all confidential and proprietary information has remained in place, the ease by which information can be removed from a business today necessitates no less than “trust but verify” suspicion.

Exactly what evidence may be enough to prove threatened misappropriation can be gleaned from several cases. The former employee must threaten — through words or actions — to disclose trade secrets. As stated earlier, it’s highly unlikely that the former employee would state his or her intentions to disclose trade secrets. A company should provide evidence indicating a lack of candor or willingness to misuse trade secrets to convince a court to order an injunction.

In Central Valley General Hospital v. Smith, a frequently cited case regarding the threshold evidence required to prove threatened misappropriation, three variants of threatened misappropriation were identified: (1) trade secrets remain in the possession of a defendant who actually misused or disclosed some of them in the past; (2) trade secrets are held by a defendant who intends to improperly use or disclose them; and (3) a defendant possesses trade secrets and wrongly refuses to return them after a demand for their return has been made.

Applying the inevitable disclosure doctrine to threatened misappropriation

In addition to the three variants identified in Central Hudson, some courts have identified the inevitable disclosure doctrine as a potential fourth type of threatened misappropriation. Under the inevitable disclosure doctrine, which predates but re-emerged in the 7th Circuit’s decision in PepsiCo., Inc. v. Redmond a court, in the absence of a non-compete, may nevertheless enjoin a former employee with knowledge of his former employer’s trade secrets from working for his former employer’s competitor if his new job duties will “inevitably” cause the former employee to rely on his knowledge of the former employer’s trade secrets.

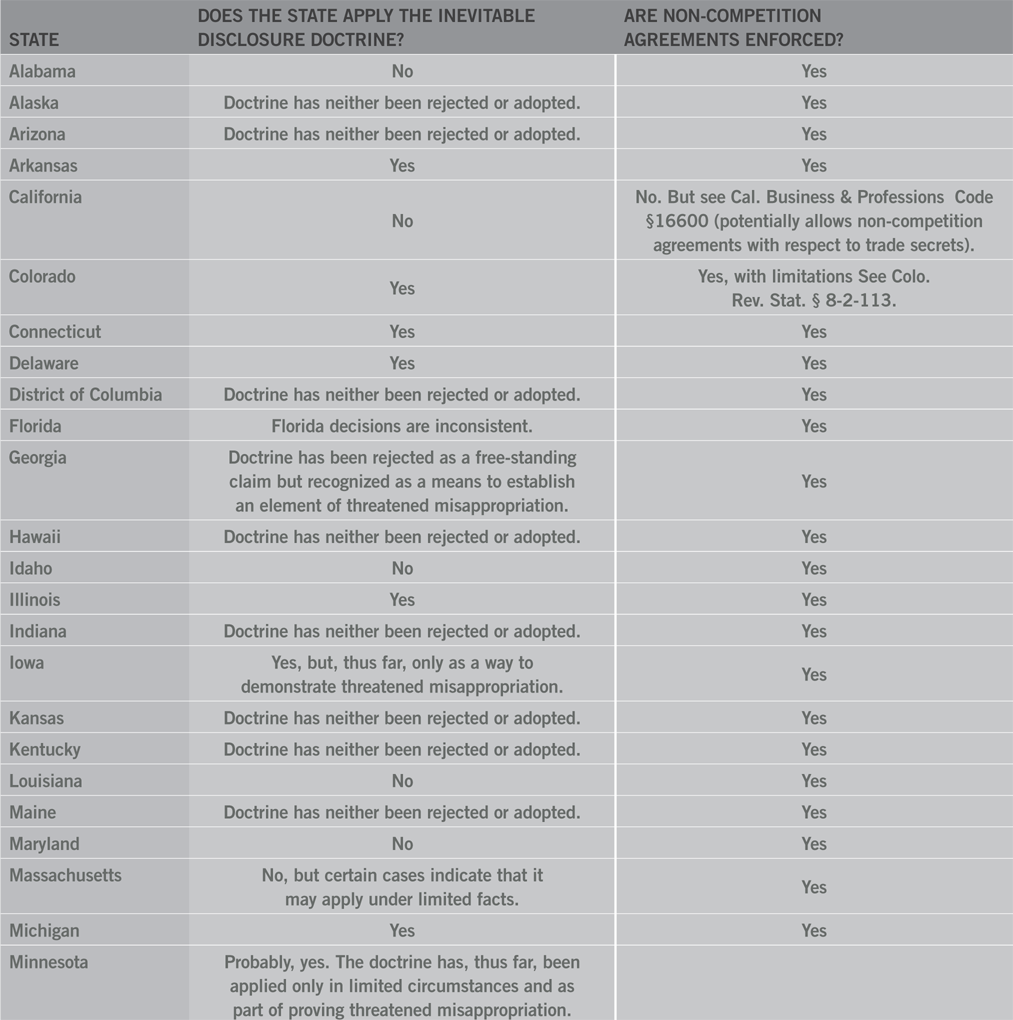

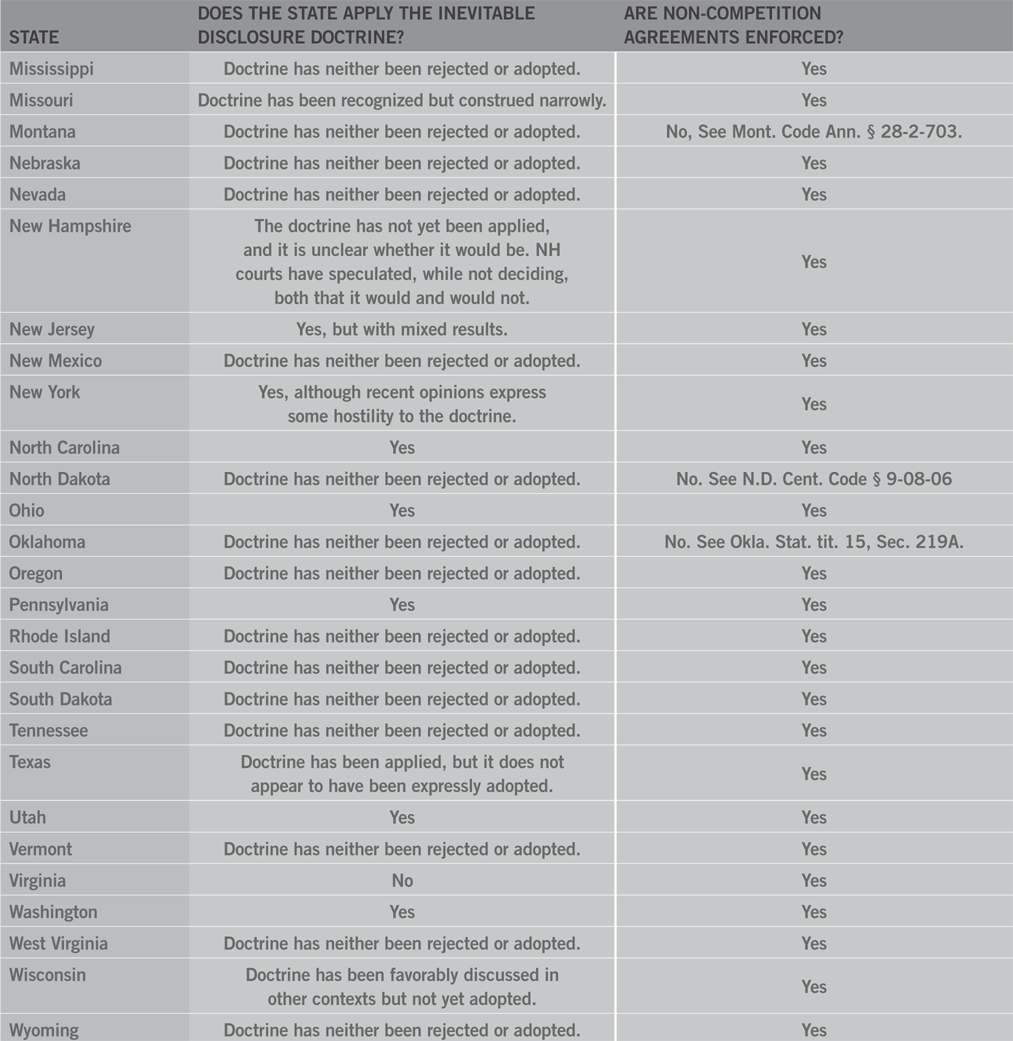

Several courts have questioned whether inevitable disclosure and threatened misappropriation are one and the same or two different theories of recovery. Regardless, the doctrine has not found uniform acceptance because it is premised upon an employee’s knowledge of trade secrets rather than his intention to misuse them and because it operates as an after-the-fact non-compete without a pre-requisite finding of wrongdoing. While the UTSA is silent on the issue of inevitable disclosure, the DTSA seems to expressly prohibit it, providing that a court may not “...prevent a person from entering into an employment relationship, and that conditions placed on such employment shall be based on evidence of threatened misappropriation and not merely on the information the person knows.” In addition, a number of courts have expressly rejected the doctrine altogether, whether as a type of threatened misappropriation or as an independent remedy. Thus, whether inevitable disclosure will have applicability in any given case will depend on the jurisdiction where the case is brought and the statute that it is brought under.

Even in courts where inevitable disclosure is not viable, the criteria that drives an “inevitable disclosure” analysis remain relevant to determining threatened misappropriation. Inevitable disclosure is driven by a former employee’s knowledge of his former employer’s trade secrets and the inevitability that he will use or disclose them in his new position without regard to whether he has an intent to misappropriate. In inevitable disclosure jurisdictions, courts ordinarily assess the likelihood of misuse without regard to whether the employee intends to do wrong. In non-inevitable disclosure jurisdictions, threatened misappropriation still requires an inquiry into the former employees knowledge and likelihood of use or disclosure of the former employer’s trade secrets. But there must also be attendant indications of wrongdoing, that is, indications of an impending wrongful use, or disclosure of the former employer’s trade secrets. Thus, even in non-inevitable disclosure jurisdictions, knowledge and inevitability of misuse of another’s trade secrets remain relevant to the determination of threatened misappropriation along with an inquiry into wrongful intent.

Assessing threatened misappropriation

The determination of knowledge, inevitability, and wrongful intent in threatened misappropriation cases is anything other than formulaic. There is no bright line against which a defendant’s conduct can be measured; rather, there are just descriptive standards such as “whether there is sufficient likelihood, or substantial threat” of misappropriation or whether there is a “...threat by a defendant to misuse trade secrets, manifested by words or conduct, where the evidence indicates imminent misuse.”

The determination of knowledge, inevitability, and wrongful intent in threatened misappropriation cases is anything other than formulaic.

As a result, courts must take each case on its own facts and make subjective judgments based on surrounding circumstances, often involving the following key variables: (1) the nature of the trade secrets at issue; (2) defendant’s knowledge and/or degree of access to the information; (3) defendant’s behavior indicative of a wrongful intent to acquire, use, or disclose the trade secrets at issue; (4) the former employer’s behavior; (5) the new employer’s behavior; (6) the degree of competition between the former and new employer; (7) similarities and differences between the former employee’s new and old positions; and (8) the nature of the equitable relief being requested.

The nature of the trade secrets

Courts often commence their analysis of threatened misappropriation by examining the characteristics of the trade secrets at issue. Courts are generally less inclined to find threatened misappropriation where the trade secrets in dispute are: (1) fragile or ephemeral, (2) transitory; (3) aged or obsolete; (4) elementary and obvious; (5) not timely, sensitive, strategic and/or technical information; (6) granular and difficult to memorize, or (7) general business information. Courts also consider the degree to which the trade secrets are specified or described in the litigation, generally disfavoring generic or categorical descriptions in favor of those that are specific. The importance of the trade secrets to the plaintiff’s business is also an important variable. A threat of harm is more likely to be found where the trade secrets in dispute are critical to the plaintiff’s business, e.g., a detailed process for keeping baked goods fresh versus aged sales information. In gauging the importance of a trade secret, some courts consider the nature of the likely harm that can befall a plaintiff in the event of the trade secret’s actual misappropriation, e.g., lost market share, lost customers. Generally, an injunction is more likely when the trade secrets in dispute are more specifically described, are technical in nature, have contemporary value, are important to the plaintiff’s business, are of extended durability, and are capable of being remembered.

The defendant’s knowledge and access to the trade secrets

In weighing the threat of misappropriation, courts also consider the former employee’s historical access to and knowledge of the former employer’s trade secrets. Courts do this by evaluating the former employee’s seniority, the extent to which he had a need for and used his former employer’s trade secrets in his prior position, his role in their development, and his recollection of them. A defendant’s generalized knowledge of a plaintiff’s trade secrets will not support a finding of threatened misappropriation. Nor will a showing of mere knowledge or mere possession of trade secrets, particularly where the defendant’s original acquisition of the trade secrets was authorized. Likewise, granular information that is difficult to memorize is more likely to weigh against a finding of threatened misappropriation, even in the case of a former senior employee who had at-will access to that information. Therefore, the risk of an injunction is greater in cases involving senior, leadership level employees of long tenure who regularly used or who helped developed the trade secrets at issue, provided the information at issue is capable of being remembered.

Defendant’s behavior

Manner of resignation

In assessing threatened misappropriation, courts appear to give considerable weight to the manner in which a defendant resigns. As a single criterion, resignations that are abrupt and without notice weigh significantly against a defendant. A lack of candor, whether by false statement or concealment, about the defendant’s future employment, particularly when the new position violates an existing employment agreement, also weighs heavily against a defendant. This is especially so when by reason of the defendant’s lack of candor, the former employer acts to its disadvantage either by continuing to disseminate trade secret information to the defendant or as in the case of CPI Card Group, Inc. v. Dwyer, the former employer agreed to renegotiate the defendant’s non-compete after the defendant misled the former employer to believe that he had not made future plans when, in fact, he had already accepted a new position in violation of his existing non-compete with the former employer’s competitor. Full and complete disclosure about future plans weighs significantly in favor of a defendant.

Candidates and new employees: Tips for vetting

The practical problems (and solutions) facing today’s in-house counsel and legal departments when trying to protect your company’s “crown jewels” require a clear understanding and review of existing nondisclosure agreements (NDAs), employment agreements, and other governing documents. This should be done not only by the legal department but also in conjunction with your HR department.

You should first inquire and thoroughly vet what prohibitions and restrictions you may be inheriting and what the “risk to reward” will be. Examples include:

- Determining a prospective employee’s scope of knowledge and access to a former employer’s trade secrets. Is this hiring an accident waiting to happen?

- Assessing degree of competition that the company has with the candidate/employee’s former employer. Is the former employer litigious? Does the former employer have a history of litigation on trade secret and employment matters?

- Having a good assessment of the scope and nature of former employer’s trade secrets. If competitive trade secrets are (inadvertently) obtained, what harm will inure to the former employer/competitor as a result of such misappropriation?

- Determining applicability of inevitable disclosure doctrine.

- Being mindful to avoid asking the candidate to perform any pre-employment tasks that are inconsistent with his duties of loyalty and confidentiality to his current employer. Mind the optics of the ask, even if the ask is innocent.

- Be mindful to not impart competitive information to the candidate which, if not reported by the candidate to his current employer, can later be argued as evidence of his disloyalty, lack of trustworthiness, and intent to misappropriate.

Pre-employment interactions with new employer

Courts considering threatened misappropriation also sometimes consider a defendant’s pre-resignation interactions with his future employer. For instance, in Xantrex Technology, Inc. v. Advanced Energy Industries, Inc., the new employer, during an interview, informed the defendant of its intent to introduce a new product that would directly compete against the former employer, which the defendant conceded concerned him as the former employer’s then-current employee. The court weighed this fact against the defendant noting, “He [the defendant] did not disclose the existence of this new competitor or its product to Xantrex.” The Xantrex court also gave weight to the fact that the defendant had prepared several pre-employment product design and market analyses

for the new employer, which the court viewed both as an indication of the defendant’s willingness to use the former employer’s trade secrets and proof of his recall of them. As another example, in Radiant Global Logistics, Inc. v. Fustenau, the court, in granting a preliminary injunction for threatened misappropriation, noted the defendant’s pre-employment efforts to help the new employer select a new office location and “going so far as installing Formica countertops and selecting carpets — all allegedly after his [plaintiff/former employer’s] work hours.” The takeaway from these cases is that pre-employment interactions with the new employer that fall short of actual misappropriation but hint of disloyalty will be weighed in favor of a finding of threatened harm.

Departure from ordinary usage of former employer’s confidential information

In the absence of proof of actual wrongful retention, use, or disclosure of trade secrets, all of the following activities by a defendant involving the former employer’s confidential information at or about the time of his departure have been weighed by courts in assessing threatened misappropriation: (1) unusual after-hours access of former employer’s premises and computer files; (2) simultaneously accessing multiple confidential documents; (3) downloading and/or printing large volumes of confidential information; (4) emailing former employer’s confidential documents to a personal email account; (5) use of portable storage devices; (6) wiping, deleting, or reformatting files on personal devices such as laptops and phones; and (7) altering or deleting a former employer’s records.

However, while suspicious conduct is probative of a former employee’s intent, it by no means guarantees a result. Courts have declined threatened misappropriation injunctions despite suspicious conduct where: (1) there was an absence of evidence that former employer’s trade secrets were actually improperly retained, used, or disclosed; (2) the defendant’s acquisition of the former employer’s trade secrets occurred during employment, was authorized, and there was no contractual obligation requiring their return; (3) where defendant destroyed or returned the former employer’s trade secret information to affirmatively avoid its misuse; (4) where the defendant gave assurances that he would not use or had no need for the former employer’s trade secrets in his new position, and (5) where the defendant remains bound by a formal non-disclosure agreement, of which there is no evidence of a violation.

Impose trade secret barriers: 10 contractual do’s and don’ts

- Avoid indemnification provisions and joint defense agreements. Take measures to avoid providing the candidate/employee with any opportunity to seek “safe harbor” when they leave or to incentivize the candidate/employee to take the risk of getting involved with threatened misappropriation.

- Consider incorporating inevitable disclosure language into the employment agreement to prohibit or restrict subsequent employment in a competitive environment.

- Clearly define and delineate the type of information that the company considers trade secret as well as employer’s ownership of all previously existing and employee created intellectual property (IP) and be very clear on what the company owns or claims rights to and what constitutes the employee’s general knowledge and experience.

- Consider contractually obligating the new employee to inform a future new employer of existing NDAs, the duty to protect trade secrets and provide language that permits you, the employer, to contact the new employer or follow up to ensure that this is being done.

- Set expectations (or incentives) that if the employee resigns honestly with appropriate notice that there will be benefits to the employee. On the other hand, you should avoid employment incentives that motivate (by bonus, spiffs, non-meritorious advancement) your employee to misappropriate trade secrets and other information or documentation.

- Consider directives prohibiting use of the former employer’s trade secrets as well as directives to existing employees to refrain from soliciting trade secret information from the new employee. The “new kid” wants to show off what they have, and the existing team members are anxious to find it out what knowledge the new employee has or may have brought with them.

- Once you have assured yourself that such trade secrets are protected, if requested, you can assure the former employer that its trade secrets will be protected.

- Specifically delineate written policies requiring the handling of confidential information during employment and upon resignation. These polices need to be developed and implemented with input from legal, HR, and compliance. Be on the lookout for employee actions that would cause the company to terminate the employee on other grounds and set the company up for a claim of wrongful termination. This puts into play a claim by the employee to seek redress from noncompete or nondisclosure/confidentiality provisions and further blur the lines between “threatened” and “actual” misappropriation.

- Delineate written policies on the use of external storage devices and the transmission of company information. From a practical standpoint, with today’s ever-changing technology, this is difficult, but at least when you find out that the former employee did download trade secret information with the intent to transfer, your claims against both the former employee and new employer will have a basis for claiming knowledge and an intentional act. This can be accomplished by requiring that all creative work be done on your company’s computers. Written, acknowledged policies should state that no personal devices, email addresses, or equipment be used to create, store, or transfer work-product generated by the employee. Additionally, the company should implement steps to prevent the deletion or destruction of all work-product.

- Finally, it is important that the company document all misuse or violations of procedures, policies, or protocols involving trade secrets. Not only does this establish a “real time” record in the event of termination but preserves the company’s position (evidence for prosecution or defense) in the event of litigation or other adversarial proceeding.

Other behavior indicative of a former employee’s intent

In finding threatened misappropriation, courts have also considered a former employee’s: (1) refusal to return and to give assurances to protect confidential information; (2) past, pre-resignation misuse of a former employer’s confidential information; (3) conduct which violates existing non-competition, non- solicitation, and non-disclosure covenants; and (4) assertion of the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination and for otherwise refusing to give testimony on trade secret issues. A defendant’s stated intent to make derivative use of a former employer’s trade secrets, that is, to create from former employer’s trade secret information something that is new or different but nevertheless competitive with former employer’s service or product also weighs in favor of finding threatened misappropriation.

Former employer’s behavior

Courts considering whether to issue a threatened misappropriation injunction also evaluate the former employer’s behavior. A former employer’s failure to use written employment agreements has in several cases weighed against the issuance of an injunction. One court noted that “... [an injunction] would, in effect, afford [former employer] a covenant not to compete, something it could have bargained for but did not.” Another court of similar mindset, in denying a threatened misappropriation injunction under the inevitable disclosure doctrine, noted: “to recognize ‘inevitable disclosure’ in this case would allow the [former employer] the benefit of influencing [former employee’s] employment relationship with [new employer] even though [former employer]chose not to negotiate a restrictive covenant or confidentiality agreement…” Courts have also shown reluctance to issue threatened misappropriation injunctions where the former employer is using the litigation pretextually to gain leverage over the employee in order to retain him or where the litigation is belied by the former employer’s post-resignation treatment of the former employee as, for example, in one case where the former employer asked the defendant to remain employed notwithstanding full knowledge of the defendant’s new job being contested in the litigation. In addition, an employer’s failure in the past to sue other departing employees under circumstances akin to the defendant’s has also been cited as a factor in declining an injunction.

New employer’s behavior

The new employer’s behavior also is a significant factor in a court’s assessment of threatened misappropriation. The new employer’s willingness to take steps to protect the former employer’s trade secrets from improper disclosure or use is among the most important criteria weighing against the issuance of an injunction. Those steps include: (1) prohibiting the former employee from disclosing the former employer’s trade secrets; (2) prohibiting other employees from soliciting the former employee for former employer’s trade secrets; (3) phasing in or restricting job responsibilities to minimize the likelihood that former employee will use or disclose former employer’s trade secrets; and (4) giving the former employer assurances that its trade secrets will be respected and protected. A new employer’s failure to impose trade secret “barriers,” its knowledge and tolerance of former employee’s pre-resignation dishonesty, misleading or unethical conduct toward the former employer; its unwillingness to assure the former employer that its trade secrets will be respected; and its alignment with the former employee under a joint defense agreement in anticipation of litigation by the former employer all have been cited as reasons in support of a threatened misappropriation injunction.

Departing employees: 10 examples of exit protocol

The key to the successful protection of trade secrets is to make sure that if the employee came with nothing ... they leave with nothing. It is important that the company establish enforceable hurdles for the departing employee and that these hurdles be acknowledged in writing by the employee. You want to ferret out and prevent the employee (once they are gone) from claiming “The information is mine,” or “I needed the material or documents to work at home,” or “I forgot I had it.” The key is a thorough and pointed exit interview prior to the employee’s departure. Some basic examples are below.

- Make a formal demand for return of company equipment and information: “Please confirm and affirm that the following represents all company equipment, property and access that You (Employee) have or had access to during your employment with Company.” List out the specific property and access information.

- Inventory and photograph returned equipment

- Maintain a chain of custody of all company property

- Enforce no deletion/no destruction policy: “Please confirm that you have not copied, transferred, or deleted any company property, records, information, or trade secrets during your tenure with (Company).”

- Mandate return of equipment “as is” with all information intact.

- Inquire about company information on personal equipment: “Please certify by your signature below that you have not transferred any company records, correspondence, or other company property to a personal or other device or to any third party.”

- Inquire about whereabouts of company information. Have the employee be specific about where information is being stored.

- Inquire about all information employee is taking with him/her. The fact remains that the goal of the company and employer is to make sure that “the Employee came with nothing … and leaves with nothing.” The only thing that the employee should leave with is their general knowledge.

- Determine records employee has accessed or downloaded proximate to their resignation and have a company representative interview the Employee to establish the reasons for such access.

- In connection with the departure, the company should forensically inspect employee’s electronic devices.

- Inquire and document the employee’s future plans.

- Document all misleading or deceptive conduct attendant to employee’s resignation.

- Obtain the employee’s affirmative written assurance that he/she will protect confidential information. While this is generally covered in the employment agreement or employee manual, a pitfall for many companies is a discrepancy in what is set forth in the agreement or manual and the actual practices/customs of the company. The wider the discrepancy, the better the employee’s defense to “threatened” or “actual” misappropriation. The best way to provide that this does not occur is to establish a written policy that “everything must be returned, and nothing can be taken,” and of course provide that the written policy supersedes any practices or customs that may arise.

Degree of competition between former and new employer

In assessing whether a former employee is likely to use a former employer’s trade secrets, courts also consider the nature of the competition between the new and former employer. The presumptive thinking is that the more directly competitive the two employers are, the more probable it is that the new employer will have the need and ability to use the former employer’s trade secrets and thus the increased likelihood that the former employee will use the former employer’s confidential information in his new position. However, the inquiry goes deeper than just classifying the former and new employers as direct versus indirect competitors or gauging the new employer’s need for the former employer’s trade secrets: “The focus should be whether the new employer can use the trade secret information to its benefit or to the detriment of the former employer.”

When assessing a trade secret’s potential benefit to a new employer and its detriment to an old employer, courts consider various factors including the similarities of the market in which the two employers operate. For example, in St. Jude Medical S.C. v. Janseen, the court declined to issue a threatened misappropriation injunction because despite the former and new employers being global direct competitors in the cardiac medical device industry, the former employee’s new and old positions were in different markets: “... the marketing strategies in Europe and the United States are ‘extremely different.’”

In addition, courts consider the new employer’s need for the former employer’s trade secrets. In Cardinal Health Staffing Network, Inc. v. Bowen, the court declined an injunction because the new employer, a direct competitor, had pre-existing relationships with some of the former employer’s customers, had devised its own business plan over a year before the former employee came aboard, and would have started its own business with or without the former employee. Courts also exam the comparability of the two employers products and services and the degree to which they are marketing to the same customers: “[Both employers] are in direct competition-they both sell comparable technology in the same markets. Indeed, both companies were on the short list of manufacturers under consideration by Sprint for a contract worth up to US$100,000,000 per year.” Other “competition” criteria include: (1) the new employer’s motivation to expand into the former employer’s product line; (2) differences in the two employer’s business models; (3) the transferability of the former employer’s trade secrets based on product design differences and (4) the degree to which they sell to differing industries or otherwise share customers.

As demonstrated by these cases, in assessing the degree of competition between a former and new employer, courts look beyond simple classifications of whether they are direct versus indirect competitors and carefully consider how the two employers compete against each other in the relevant market.

Similarity between new and former positions

The similarities between a defendant’s new and former jobs also are indicative of whether he is likely to misuse his former employer’s trade secrets. The inevitability or likelihood of misuse is assessed by considering the nature of the trade secrets at issue relative to the nature of the employee’s past and future work. A new position with identical or nearly identical job responsibilities with a direct competitor in substantially the same profession is more likely to result in a finding of threatened misappropriation, particularly in those courts applying the inevitable disclosure doctrine. However, the inquiry encompasses more than just a generic comparison of job responsibilities. Rather, the court must identify the specific trade secrets at issue; determine the extent to which they fall within or are embraced by the former employee’s new position; determine whether they are capable of being remembered by the former employee and whether, because of the former employee’s role in their development or prior use, the former employee’s past involvement with the trade secrets was so significant that he “... cannot but help consider them while performing duties for the [new employer].”

The new employer’s willingness to take steps to protect the former employer’s trade secrets from improper disclosure or use is among the most important criteria weighing against the issuance of an injunction.

For instance, in Del Monte Fresh Produce v. Dole Food Co., one of Del Monte’s highest-ranking executives and senior scientists resigned to take an executive level job with Del Monte’s global competitor, Dole. While there were some differences in the two positions, the court noted that some of the duties were the same or similar. While at Del Monte, the former employee had access to highly confidential information that involved all areas of the company’s business over which he had responsibility; however, his job was to oversee and audit, not hands on production. “This means that [the former employee’s] knowledge of formulas, processes, and techniques employed at Del Monte local farming operations was minimal. Additionally none of this work required him to formulate or apply specific processes, formulas or techniques...” The former employee also claimed minimal memory of Del Monte’s trade secrets, a claim corroborated by one of Del Monte’s trade secret experts who also “... could not remember or articulate specific proprietary protocols...” On these facts, the court declined to issue a threatened misappropriation injunction because “although [former employee] had thorough knowledge of the business ... he cannot remember this information with precision.”

Dole shows that mere historical access to trade secrets is insufficient. Merely taking a comparable job with a direct competitor is also not enough. What matters is the level of trade secret knowledge the former employee is bringing to the new employer, the degree to which he applied that knowledge day to day in his former position and the extent to which, by reason of his past use and involvement in the trade secrets, he will apply that knowledge in his new position. Further, it is critical that plaintiff describe the trade secrets at risk for the court with as much specificity as possible. The relevance and the weight to be given to the similarities between the new and former positions are illuminated by proof of the former employee’s memory or ability to remember the specific trade secrets he used day to day in his previous position. Only with that knowledge can a court gain insight into the inevitably or likelihood that a former employee will misuse his former employer’s trade secrets in his new position. Without such evidence, an argument asserting similarities between two jobs rings hollow.

The nature of the equitable relief being requested

Finally, the nature of the relief being requested also influences the likelihood of an injunction. The scope of provisional or permanent injunctive relief in threatened misappropriation cases has included prohibiting new employment altogether, placing restrictions on new employment; enforcing existing or newly fashioned non-compete, non-solicitation, and non-disclosure obligations; and ordering an defendant to account for trade secret information in his possession. In the absence of an enforceable non- compete, courts generally disdain prohibiting new employment, which the DTSA also expressly prohibits, permitting instead injunctions which restrict employment provided they are “based on evidence of threatened misappropriation” or which do not “... otherwise conflict with an applicable State law prohibiting restraints on the practice of a lawful profession, trade, or business ...”

The Maryland Court of Appeals, in LeJeune v. Coin Acceptors, in rejecting the inevitable disclosure doctrine as a form of threatened misappropriation, noted that in lieu of restricting employment a court fashioning a threatened misappropriation injunction should be thinking more narrowly: “Rather, the focus should be on precluding the disclosure of trade secrets.” As a general rule, the remedy for threatened misappropriation should be tied to the gravity of the circumstances. Seeking a “no employment” injunction should be reserved only for those cases with an existing non-compete or for UTSA cases where nothing less than a prohibition on employment will suffice.

There’s no need to wait for actual loss of trade secrets

Employers do not have to await the actual loss of their trade secrets before taking legal action against a departing employee who wishes to leave with more than the last paycheck. Both the UTSA and the DTSA permit courts to enjoin a former employee’s threatened misappropriation of trade secrets. That is, employers may seek to enjoin a former employer from wrongfully acquiring, using, or disclosing its trade secrets upon proof that falls short of proving actual misappropriation but nevertheless exposes a substantial threat of its imminent occurrence.

There is no bright line, however, that distinguishes an actionable threat from non-actionable suspicion. The judgment of whether a cognizable threat exists is made subjectively by courts, case to case, upon consideration of evidence directed to several key variables: the nature of the trade secrets at issue; the defendant’s knowledge and/or degree of access to the trade secrets at issue; behavior indicative of a defendant’s wrongful intent to misappropriate those trade secrets; the former employer’s behavior; the new employer’s behavior; the degree of competition between the former and new employer; the comparability of the former employee’s new and old positions; and the nature of the equitable relief being requested. From consideration of evidence directed to these factors, courts must decide whether there is a sufficient likelihood, or substantial threat of misappropriation. Upon making such a finding, a court may then fashion an equitable remedy which proportionally mitigates the threat of misappropriation without encroaching upon the former employee’s right to make a living through his general knowledge and experience.

References

162 Cal.App.4th 501 (Ct. App. 2008).

54 F3d. 1262 (7th Cir. 1995).

Bimbo Bakeries USA, Inc. v. Botticella, 613 F.3d 102, 114 (3d Cir. 2010).

FLIR Sys., Inc. v. Parrish, 174 Cal. App. 4th 1270, 1279, 95 Cal. Rptr. 3d 307, 316 (2009).

CPI Card Grp., Inc. v. Dwyer, 294 F. Supp. 3d 791 (D. Minn. 2018).

Cargill Inc. v. Kuan, No. 14-CV-2325-RM-MJW, 2014 WL 5336233, at *4 (D. Colo. Oct. 20, 2014).

LeJeune v. Coin Acceptors, 381 Md. 288,322, 349 A.2d 451,471 (2004).

Conley v. DSC Commc’ns Corp., No. 05-98-01051-CV, 1999 WL 89955, at *5 (Tex. App. Feb. 24, 1999).

H & R Block E. Tax Servs., Inc. v. Enchura, 122 F. Supp. 2d at 1075-1076.

18 U.S.C. § 1836(b)(3)(A)(i)(I) and (II).

ACC EXTRAS ON… Trade secrets

ACC Docket

Trade Secret Hygiene for Current Employees (Dec. 2019).

Best Practices to Protect Trade Secrets in Failed Acquisitions and Customer Relationships (Nov. 2019).

Securing Against Trade Secret Pitfalls and Dangers Arising from Employee Mobility Situations (Oct. 2019).