CHEAT SHEET

- Red teaming. Adaptable to many contexts and always customized to a particular organization, red teaming is a strategy to expose weaknesses and threats – and reduce risk – through alternative thinking.

- International teams. Assembling an international red team will require effective use of technology, translations, and cultural competency. The team should operate independently, resist groupthink, and maintain records of thought processes and final results.

- Exercises. When seeking to anticipate and avoid business crises, explore potential crises on a macro level, map stakeholders, and test a crisis management plan or policy for weakness.

- Regulations. Consider the data protection and privacy laws and discovery requirements in your jurisdictions when developing policies to mitigate risk.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact businesses, demonstrating the ramifications of a global crisis, companies need to identify new and creative tactics to stay ahead of the next catastrophe. Anticipatory strategies help a business not only foresee a crisis, but to achieve the optimal goal of successful crisis management: avoiding the crisis altogether.

This article explores how businesses may adapt a modern crisis anticipation strategy to the international setting. Red teaming, a set of tactics originally developed by the intelligence community, and later adopted and modified in the military and cybersecurity spheres, has inherently nationalist roots. However, a novel application of these tried-and-true approaches to identifying potential threats and assessing impending crises in the international setting results in a toolbox of strategies for multinational businesses seeking to refine their approach to crisis management. The challenges unique to crises that cross borders, including privacy and cybersecurity communication concerns, will also be explored. ACC

A brief history of red teaming

Red teaming garnered media attention in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks when the then-director of central intelligence created the CIA’s “Red Cell.” The Red Cell was a group assembled to think contrarily about national security in order to challenge and improve the agency and its analyses of intelligence. Today, the Red Cell is credited with thwarting numerous attempted terrorist attacks against the United States through the use of red team strategies.

Red team exercises are frequently implemented by militaries throughout the world. The red team strategy has also been adapted to the cybersecurity sphere, informing how penetration testing (PEN testing) and similar drills are implemented, in order to identify weaknesses in cybersecurity platforms.

Defining red teaming

There are as many definitions of red teaming as there are red team strategies to explore and apply when hoping to identify and avoid potential future crises. The University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies’ Red Team Handbook: The Army’s Guide to Making Better Decisions provides a workable explanation: “Red Teaming is a flexible cognitive approach to thinking and planning that is specifically tailored to each organization and each situation.” Red teaming “is conducted by skilled practitioners normally working under charter from organization leadership” using “structured tools and techniques to help us ask better questions, challenge explicit and implicit assumptions, expose information we might otherwise have missed, and develop alternatives we might not have realized exist.”

In practice, red teaming finds weaknesses and identifies threats. Red teaming is a process by which independent and culturally sensitive alternative thinking is encouraged from a variety of perspectives to challenge assumptions. The end result aims to reduce risks, and identify and maximize opportunities. Red teaming presents an array of thought paradigms to encourage brainstorming, resulting in extensive and creative assessments of threats. Red team strategies are always bespoke to a particular organization and a particular situation. They are versatile, and when considered pragmatically, adaptable to the international setting.

International red teaming: A novel approach

While red team strategies are ripe for application in a multinational context, certain adjustments should be made to maximize productivity across culturally distinct geographies.

Teamwork across borders

Red team results are only as strong as the assembled team. Assembly of a broad-based team is key when looking to assess and avoid existential business disasters. The red team should include in-house members from various corporate departments (legal, marketing, corporate security, human resources, and information technology), in addition to members from the company’s outside counsel, consultants, and vendors (legal counsel, forensic, and IT support). In-house members bring an understanding of the company’s policies and priorities to the team, while external members increase value by diversifying the red team’s perspectives and various areas of expertise.

Assembling an international red team is predictably more complex than gathering a group in a single location for a strategy session. Technology will be paramount in the red team’s ability to work, and ideally, all members should participate via video conference. Materials necessary to the red team’s tasks — drafts of policies or relevant media coverage — should be awaiting each member in their respective locales. When inviting a variety of perspectives across borders, be prepared to involve translators to facilitate communication and translate documents that may become important to the red team’s work.

When the red team convenes in an anticipatory capacity, scheduling will be no more difficult than selecting a time that is feasible across time zones. However, when the red team is called upon to help address an active and ongoing crisis, it is possible some members may be engaged at inopportune times or in the middle of the night. Communication about the expectations of the team upfront is essential to prepare the team for these realities. Red teams consistently address high-stakes issues, and support staff should be available in each location to support the red team members even when working during off-hours.

Culture’s role in a crisis

Culture plays a significant role in crisis response. Studies have shown that culture influences the way individuals respond to an emergency. When anticipating, managing, or recovering from a multinational crisis, cultural competency is an inherent part of the effort. Accordingly, the red team should be comprised of individuals representing the cultures present at the company, with understandings of various cultural needs and expectations that may be implicated in a catastrophe, to account for the interplay between culture and crisis. For example, if a majority of employees in a given jurisdiction or location identify with a particular culture, the norms and beliefs of this culture may influence their perspectives on accessibility to mental health counseling or treatment, or the national perception of a particular industry, which could play a role in a company’s crisis response actions depending on the nature and scale of the crisis.

When anticipating, managing, or recovering from a multinational crisis, cultural competency is an inherent part of the effort.

The jurisdiction’s familiarity with and acceptance of the US legal system, scope of relevant discovery, aggressiveness of certain proceedings, and application of jury awards or punitive damages can also impact the proposed response and the need for public relations/crisis communications. In some locations, too, face-to-face meetings might be needed to confirm plans of action, and questioning the decisions of a team leader will not be common or forthright. The importance placed on the expectation of personal privacy is also an issue that needs attention based on the different jurisdictions and varying privacy laws.

The red team should include members who understand these cultural perspectives, as well as cross-border laws and policies and the local legal environment to ensure crisis management and response plans are effective and culturally competent. The red team should be reminded that all policies or practices developed by the team must account for specific culture-related needs of the businesses’ employees and clients in the various geographies impacted by the potential catastrophe or the corresponding response plan.

If the red team identifies a need for better understanding of one culture or another in connection with its exercises, they may wish to invite the participation of a cultural broker — such as a community leader within the organization or in a given location who understands the community, and its norms and expectations. Cultural brokers may serve as a resource in terms of employee or client feedback regarding the company’s past responses to crises, and therefore serve as a resource regarding where the business may improve in the future. Cultural brokers may also shed light on the various expectations red team members may have for meetings, assignments, and how the team executes tasks.

Goalsetting in the international setting

Setting clear goals for each meeting of the red team is especially important when members are scattered across the globe. While the specific goals for any given red team will be bespoke to the organization that assembled the team and the situation, policy, or procedure to be analyzed, some general guidelines apply to all red team exercises:

- Operate independently. The red team cannot be influenced by forces outside the process, and management must “buy into” the red team’s process and results. Participants must be free of the restraints of organizational hierarchy, and team members from all ranks must be free to challenge ideas and reasoning without fear of retribution.

- Resist groupthink. Groupthink is the psychological phenomenon of making decisions as a group in order to prioritize conformity and harmony — at the expense of creativity. Groupthink is the enemy of red teaming, and team members should engage in individualized thinking to ensure the most comprehensive results in red team exercises.

- Records are key. The red team’s thought processes and final results should be meticulously recorded. This record will serve as one of the long-term benefits of the red team exercise.

The independence and teamwork of the red team is key.

When coordinating red team exercises across borders, directed by these guidelines, communication of goals in advance of meetings will be crucial and projecting the red team’s projects across the coming months is advisable. While the red team will certainly address large-scale, global threats to the business, it is wise to also task the team — and its members in various geographies — to consider the interplay of smaller-scale threats that may only affect certain locations. If this month’s red team exercise asks the team to narrow in on a crisis that may threaten a plant in one location (say, a CAT-5 hurricane and a plant located in North America), the team will benefit knowing next month’s exercise will dig into a potential threat at another of the company’s locations. Red team members may have valuable insight for smaller-scale threats to the business in other corners of the globe.

In the litigation or investigation context, consideration should be given to the discoverability of such exercises, application of self-critical analysis privilege, and how the analysis could be interpreted or misinterpreted outside of the company.

Red team exercises to apply across borders

Red team exercises are numerous and ever-emerging. Now equipped with an understanding of how red teaming should be modified to fit the international context, we propose three exercises to explore when seeking to anticipate and avoid business crises:

Signposts of change

This exercise explores potential crises on a macro level, by identifying warning signs that accompany business threats. The red team identifies a phenomenon the business would like to anticipate; creates a comprehensive list of activities, events, or other observable phenomena expected to precede the situation’s occurrence; and revises the list each time the situation occurs. This exercise feeds the business’ proverbial watchdog, supplying the company with a reference list from which to foresee future large-scale threats.

Stakeholder mapping

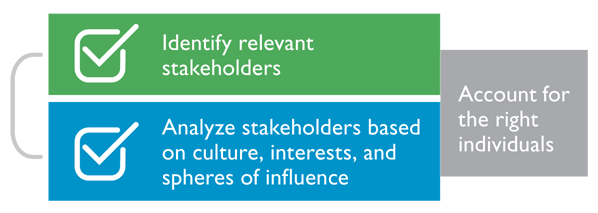

This exercise anticipates the interests, perceptions, and actions of various groups in complex scenarios, to ensure that plans or decisions are not sabotaged by a lack of appreciation of various perspectives. This method may be applied to test the vulnerabilities of crisis management plans developed by the red team. The red team identifies all relevant stakeholders who may be impacted by the crisis or the management plan, and then analyzes the individuals identified in terms of: culture, individualizes interests, and spheres of influence. Stakeholder mapping helps ensure crisis management plans account for all individuals within the business who are likely to be impacted by a crisis, and may identify potential assets to help support the plan.

Premortem analysis

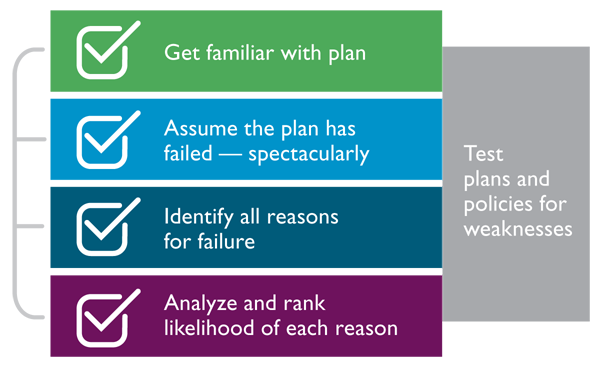

Premortem analysis is also used to test a crisis management plan or policy for weaknesses. The red team thoroughly familiarizes itself with the plan; assumes — for the sake of the exercise — that the plan has spectacularly failed; identifies all the reasons why the plan may have failed; and analyzes the likelihood of each reason. This exercise lets the red team revisit and revise the original plan or policy to avoid the reasons for failure identified in the premortem analysis.

In the litigation or investigation context, consideration should be given to the discoverability of such exercises, application of self-critical analysis privilege, and how the analysis could be interpreted or misinterpreted outside of the company. The self-critical analysis privilege may protect “protect the opinions and recommendations of corporate employees engaged in the process of critical self-evaluation of the company’s policies for the purpose of improving health and safety.” Notably, there is little authority addressing the discoverability of red team materials at this time.

Added complexities for managing an international crisis

When managing an active crisis or engaging a red team across borders to identify potential threats, remain mindful of the possibility of future litigation. In-house counsel should consider whether your jurisdiction is one of the current contracting parties to the Hague Convention of March 18, 1970 on the Taking of Evidence Abroad in Civil or Commercial Matters, and understand the process it sets out for facilitating cross-border transfers of data or documents via letters of requests exchanged by the requesting and receiving states. Remain aware that data protection and foreign privacy laws may compound the complexity of discovery — particularly eDiscovery.

Foreign laws may impose restrictions on collection, review, and dissemination of personal data. There may be special implications regarding the accessibility of comingled data available to employees in different parts of the world. Partnering with the expertise of outside counsel may enhance this analysis, as familiarity with the EU’s Directive on Data Protection, Japan’s Act on the Protection of Personal Information (PIPA), and other regulations applicable to a cross-border dispute is essential. For example, some provisions of Japan’s PIPA may apply to conduct taking place outside of Japan, including businesses located outside of Japan that handle “personal information” acquired during the course of providing goods or services to residents in Japan. In such circumstances where a business located outside of Japan obtains “personal information” (say, though a website online question form), this acquisition of data may be deemed to take place within Japan, thereby falling subject to the requirements of Japan’s PIPA. Partnering with external counsel thoroughly familiar with such data privacy regulations is the best means by which to avoid running afoul of these provisions.

Signposts of change

Stakeholder mapping

Premortem analysis

Be aware that tensions may exist between US discovery requirements and these foreign data privacy laws. When balancing these requirements, counsel may “(1) identify the cross-border data sources that apply to the matter; (2) diligently research applicable laws that apply to these sources; and (3) confer with specialized privacy counsel how best to preserve data from these sources in compliance with the law.”

Strategize early on to develop comprehensive discovery and privacy policies to help balance these competing considerations. Be prepared to work closely with the IT department to understand the accessibility of data involved, and where such data are maintained. Whether the company’s foreign data are “easily accessible” to its US counterparts lies at the heart of this analysis and understanding where servers are located may help preempt demands for foreign data.

Conclusion

With modest modifications, risk assessment and red team exercises enable a business to forecast and avoid crises. While not all catastrophes may be avoided, striving to identify problems before they arise and taking action early will best position a company to prepare for and respond to a crisis with global implications.

ACC EXTRAS ON… Multinational organization risks

ACC Docket

The Real Game of Risk: International Sanctions (June 2020).

Avoid Employment Litigation (May 2019).

How In-house Counsel Can Help Their Organizations Navigate Global Uncertainty (Oct. 2019).

ACC HAS MORE MATERIAL ON THIS SUBJECT ON OUR WEBSITE. VISIT WWW.ACC.COM, WHERE YOU CAN BROWSE OUR RESOURCES BY PRACTICE AREA OR SEARCH BY KEYWORD.

References

See Bryce G. Hoffman, How Your Business Can Conquer the Competition by Challenging Everything (2017), at 34-36.

See U.S. Department of Defense, Red Teaming, Past and Present – Case Studies: Field Marshal Slim in Burma, T.R. Lawrence in World War I, Operation Iraqi Freedom, Decision-Making Theory, Challenging Organization’s Thinking (2017) (study examining historical and contemporary uses of red teaming).

See, e.g., Charles Y. Yang, “Demystifying Japanese Management Practices.” Harvard Business Review (Nov. 1984); Ben L. Kedia, Anada Mukherji, “Global Managers: Developing a Mindset for Global Perspectives.” Journal of World Business (Vol. 34, 1999); Robert T. Moran, Philip Robert Harris, Sarah Virgilia Moran. Managing Cultural Differences: Leadership Skills and Strategies for Working in a Global World (8th ed. 2011).

See David Gallop, Chris Willy and John Bischoff. “How to Catch a Black Swan: Measuring the Benefits of the Premortem Technique for Risk Identification.” Journal of Enterprise Transformation (Vol. 6, 2016).

In re Block Island Fishing, Inc., 323 F.Supp.3d 158, 160 D. Mass. 2018).

See Michael C. Zogby and Yodi S. Hailemariam, Doing Discovery in Japan? Ganbatte! Privacy, Propriety and Preparation, Law Technology News, at 2 (Mar. 6, 2018).

Practical In-House Approaches for Cross-Border Discovery & Data Protection, The Sedona Conference, Vol. 17, No. 1, at 410 (2016).

See International Principles on Discovery, Disclosure & Data Protection in Civil Litigation (Transitional Edition), The Sedona Conference, at 6-7 (Jan. 2017).