CHEAT SHEET

- Speeding up litigation. The amendments to the FRCP should drive speed in early case assessment and overall case management.

- Making discovery proportional. The change to Rule 26 makes discovery proportional to the needs and stakes of the case and gives the court enforcement power to enforce this.

- Bringing litigation up to speed. Changes to Rule 37 reflect the importance of electronic discovery in today’s legal environment.

- More to come. Wording may change but the true test of the new rules will be in the interpretation of the courts as these issues are litigated.

Imagine a former employee files gender-based harassment and discrimination claims against your company in federal court. The plaintiff claims a series of former supervisors harassed him and that the company discriminated against him. After some initial document production, the plaintiff moved to compel additional documents, including the personnel records of those who allegedly harassed him and also personnel records for all employees without protected characteristics at the company. As the defendant, you object on a variety of reasons, including the broadness of the request and the privacy interests of other employees. Based upon the new proportionality standard, the court may well rule that the plaintiff would be entitled to the documents for the specifically named alleged harassers, and the specifically identified and limited comparable employees, because it would be relevant and proportional discovery to the plaintiff. However, it would be equally likely that the court would deny the motion to compel as to the other employees (e.g., non-harassing managers, HR representatives, etc.) because the relevance would be tangential and not proportional to the plaintiff. In-house counsel managing litigation should understand the recent amendments and the logic behind them.

The high points of the revised guidelines:

- Amendments became effective December 1, 2015, and apply to all pending proceedings and subsequently filed civil cases to the extent application is “just and practicable.”

- Advancement of timelines around service, scheduling orders, and certain discovery mechanisms to drive early case management and better manage delay.

- Revised Rule 26 focused on discovery being “proportional to the needs of the case,” with a focus on techniques for the same.

- With the increasing importance and growth of the world of electronically stored information, amendments focused on including reworked sanctions provisions relating to failures to preserve electronically stored information.

- Additional changes to reflect the federal courts’ experiences in e-discovery since the last round of amendments.

For many of us, it has been years since we took a wholesale deep dive into the annals of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP). Even the mention of delving into the minutiae of the FRCP harkens back to days outlining, Shepherdizing cases, and thumbing through the North Western Reporter. Erie Railroad anyone?

There have long been shifting sands in the land of “hows” with the FRCP — namely with the way litigation is conducted in federal court, and systemic changes in how business is conducted and records are kept. To that end, it was long overdue when the new amendments to the FRCP finally went into effect. Although reasonable minds may differ, many believe them to be the most significant changes to the rules of discovery ever implemented.

Getting a jumpstart on digesting these amendments is important to ensure your company’s litigation management processes, and that cost management procedures match the current state of the FRCP. This article summarizes the key changes from those amendments, which fall into three primary buckets: (1) driving speed in litigation and early case management, (2) infusing greater proportionality in the discovery process, and (3) changes focused on the shifting area of electronic discovery, and the preservation of electronically stored information (ESI).

Driving greater speed in litigation and early case management

A number of changes in the rules focus on driving speed in not only early case assessment, but also in overall case management. The changes center primarily on three rules: Rule 1, Rule 4, and Rule 16. These changes are highlighted below:

- Rule 1 – Scope and purpose: The changes to this rule sets the table for the changes relating to speed, making it clear that the parties, in addition to the courts, are expected to drive the “just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of every action and proceeding.”

- Rule 4 – Summons: The time limit to have the summons and complaint served on a defendant has been reduced from 120 days to 90 days after the plaintiff files the complaint. In addition, the rule has been amended to shift some burden to the defendant to reduce delay and expense in service by including the requirement that a US defendant who fails to return a waiver of service request from a US plaintiff pay the cost of that service.

- Rule 16 – Pretrial conferences, scheduling, management: The amendments shortened the time for a court to issue its scheduling order 90 days (or earlier) after service on the defendant, or 60 days after any defendant appeared. Previously, the timelines were 120 and 90 days, respectively. Additional changes indicate scheduling orders may include preservation and claw back agreements, while also directing parties to request a court conference in advance of engaging in motion practice on discovery disputes.

Infusing proportionality into the discovery process

The second significant area of focus of the amendments drives greater proportionality in the discovery process. These changes are evident in amendments to Rule 26 and Rule 34.

The changes to Rule 26 are the most significant:

- Rule 26(b)(1) – The amendments add a requirement that discovery must be “proportional to the needs of the case, considering the importance of the issues at stake in the action, the amount in controversy, the parties’ relative access to relevant information, the parties’ resources, the importance of the discovery in resolving the issues, and whether the burden or expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit.” In addition, the amendment explains ”information within this scope of discovery need not be admissible to be discoverable.”

- Rule 26(c) – The amendments add clear language that empowers the court to allocate costs associated with discovery within the range of protective orders that a court may issue.

- Rule 26(d) – The amendments permit parties to issue Rule 34 requests for production 21 days after service of the summons and complaint. A Rule 26(f) discovery planning conference need not to have been held, however, the computation of time for responding to those rule 34 requests will be deemed served as of the occurrence of the Rule 26(f) conference (30 days subsequent).

The changes to Rule 34 reflect the revised timing on the ability to issue the requests, and the running of response times from the Rule 26(f) conference. Moreover, in rule 34(b)(2)C), the amended rule requires a party issuing objections to a document request to “state with specificity the grounds for objecting and if “any responsive materials are being withheld” on the basis of that objection.

Focus on changes driven by electronically stored information and e-discovery

The world of electronic discovery has exploded in the past 15 years. It is a critical focus area for litigators, for businesses, and for the courts. To that end, it is no surprise that the amendments place significant focus on shifting the FRCP’s nuances to reflect the federal courts’ experiences in that space since the last round of amendments.

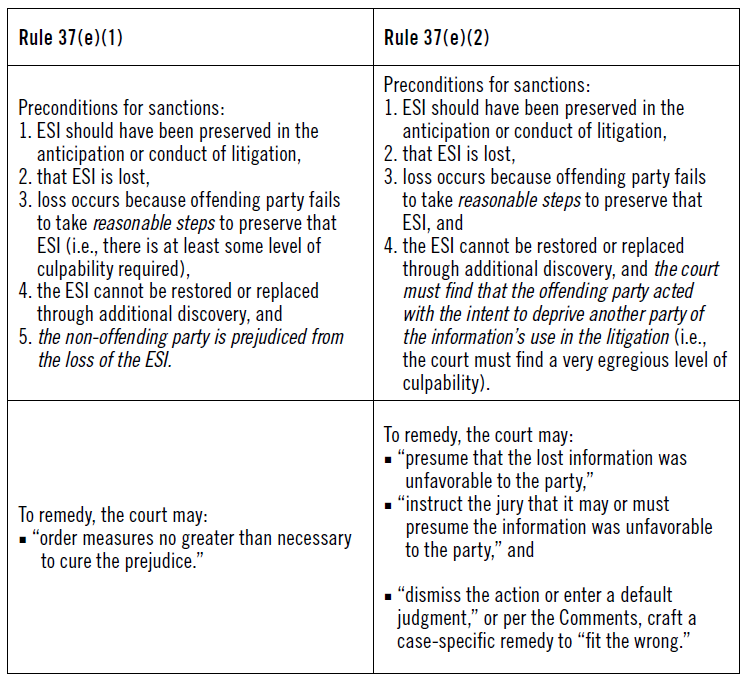

Rule 37 shows the most significant changes in this space. In addition to explicitly calling out the right to move to compel the production of documents, versus the right to inspect documents, significant changes focus on the new standard for imposing sanctions on a party who fails to preserve ESI. The below table summarizes Rule 37(e)’s amended sanctions’ preconditions and applicable remedies designed to drive consistency across courts in their response to e-discovery violations. Under that rule, there are two levels of sanctions, baseline sanctions under rule 37(e)(1), and severe sanctions under Rule 37(e)(2):

Final word or more to come?

As with any shift in procedural practice, these amendments are by no means the final word, and are likely the start of more to come. Although significant guidance is provided between the wording changes in the rules and the Committee notes, the devil will be in the details and the federal courts’ interpretation of how they will be applied to pending and future cases. No doubt the true meting out of the impact of these changes will be the interplay with each federal courts’ local rules and procedures, which are likely to vary from district to district as these issues are litigated.

However, given the scope and significance of these amendments, there is no doubt in-house counsel will need to proactively plan for how these changes will impact their companies’ litigation, and more importantly, their companies’ operations, data retention, and litigation hold processes. As the practicalities of these amendments come to fruition over the upcoming months, in-house counsel should stay attuned to key rulings and related trends from the federal courts’ rulings.