Banner artwork by robin.ph / Shutterstock.com

Colm MacKernan, an international technology lawyer, sits with down with Veronica Pastor, deputy general counsel of ACC, to talk about the recent US Supreme Court Decision in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith et al. and its impact on artificial intelligence.

The Warhol decision

Veronica Pastor: Colm, you have an interesting legal background — you’ve represented clients in private practice in Europe, the United States, and Asia, and you’ve been General Counsel at ARM and Psion, two technology companies that have brought us everything, from the palmtop computer and the original memory card to the ubiquitous ARM chips used in every cell phone, tablet, most servers, Wi-Fi, and many laptops. Your law firm, Origin, has acted as house IP counsel to King.com, makers of Candy Crush, and TomTom, the creators of the personal navigation device. You arbitrate and litigate in the United States, Europe, and Asia, and manage local counsel in several jurisdictions. Recently we were talking about the Andy Warhol case before the US Supreme Court, and you mentioned that the issue, fair use, has a wide array of potential implications for intellectual property law and artificial intelligence, can you explain?

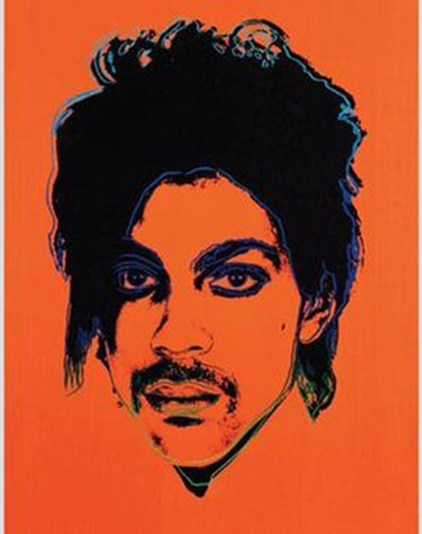

Colm MacKernan: Andy Warhol had, when alive, licensed a photo of Prince that Lynn Goldsmith had taken in 1981 and that had been used in numerous magazine illustrations. Warhol paid Goldsmith US$400 to use that photo to create a two-tone silk screen version to be used in a Vanity Fair article. He then also used it in his own prints. Decades later, Warhol is dead, and his foundation strikes a US$10,000 deal for Condé Nast to use the same Warhol prints in another magazine. At that point Goldsmith says no, that’s infringement, and the Warhol Foundation sues Goldsmith, seeking a declaratory judgment that it was fair use. They took it all the way to the US Supreme Court.

Pastor: The Warhol decision was about “fair use” — a defense to copyright infringement that really only exists in the United States. Copyright is based on the pretty universal notion that the author of an original work should have the exclusive right to profit from that work. In the United States that protection initially lasts for the life of the author plus 70 years. Copyright includes not just the right to own and control the primary work, like a novel, but also all derivative works, such as plays, films, etc. So, Shakespeare would have rights in West Side Story if he had not been dead for 400 years.

In the United States these rights are protected by Section 103 of the Copyright Act, and actual damages plus attorneys’ fees are often awarded, and there’s the possibility of statutory damages. There’s a similar defense in the United Kingdom called “fair dealing.” The rest of the world does not generally have this concept, but may consider it relevant to damages. So, what is “fair use” and how does it apply?

The Warhol decision was about "fair use" — a defense to copyright infringement that really only exists in the United States.

The nature of fair use

MacKernan: The fair use doctrine is a defense based on freedom of expression. It was codified in 1973 as Section 107 of the Copyright Act. In essence, fair use says that, in particular circumstances, you can use a copyrighted work if the purpose is teaching or research, commentary (including criticism and satire), or news reporting. In deciding whether a particular derivative work infringes copyright, the court will look at four factors:

- Purpose and character of the use;

- Nature of the copyrighted work

- Amount or substantiality of the portion used; and

- Effect of the use on the potential market for or value of the work.

There’s really no bright line defense of fair use. It’s very fact specific — and you need a lot of facts to fall your way.

The fair use doctrine is a defense based on freedom of expression.

Pastor: US law sets up a tension between derivative works and fair use: Derivative works are infringing, but sometimes, under certain circumstances, the derivate work is a “fair use” that doesn’t infringe. What does that have to do with AI and Andy Warhol?

MacKernan: The nature of use — what it’s used for — and the extent of the taking has been sort of rolled together into a question: How “transformative” is the new work? This was what some commentators were predicting would be the “big deal” for AI in the Warhol case — that it would set out some bright line transformation standard that AIs like say, ChatGPT, could use to say, “Look, we’ve transformed enough so there is no infringement,” but in the end the decision was like the dog that didn’t bark.

Pastor: It didn’t bark?

MacKernan: No, it didn’t, because the Supreme Court judges didn’t have to take a general position. They issued a very fact-specific decision, focusing particularly on a key fact: the Warhol silk screen is competing with the original Goldsmith photo to be used for the same purpose, in the same way, in the same magazines. It’s a very fact-specific decision that didn’t focus on the question of transformation as a key factor. It talked about it, but it wasn’t the central factor. So, really, nothing new for AI, but that too is a big deal.

Pastor: Why?

Where is AI headed?

MacKernan: Because AI is heading in tricky directions. A few years ago, people in the AI community were fairly sanguine about the intellectual property issues AI created. Mostly, they were talking about what intellectual property rights a creator or an inventor might have in a work or invention where they had used AI to create something using defined sets of works, information, or knowledge — a fixed knowledge-base. That was simple. But things become complicated once you start thinking about where AI is going, for example using web-crawlers like Common Crawl to look at everything on the internet that doesn’t prohibit it and using a wide-open knowledge base.

Pastor: Hang on — you can stop web-crawlers surveying your website?

MacKernan: Yes, it’s one of those obscure things few people know using robots.txt, but you need to be careful or Google, Bing, DuckDuckGo, and other search engines might not return your web-pages in searches. The latest generative AIs are using web-crawlers that don’t restrict themselves. They look at potentially everything — photo libraries, JSTOR (which is almost every significant academic journal), patents, open-source software — and use that to answer questions and create things. Some of these sources have traditionally protected their materials with things like digital watermarks and copyright traps which the AI agents often remove or modify in works they create.

The latest generative AIs are using web-crawlers that don't restrict themselves.

But suppose I ask one of these AI agents to create a picture, says Holbein’s obsequious rendition of Henry VIII in the style of Andy Warhol — and I then sell copies. Is that infringing Warhol? The AI agent will have looked at many Warhol works to do this. How far can I go in copying Warhol’s style before I’m infringing and Warhol’s Foundation sues? Did the AI agent infringe or did I? Or was it my employer? What is copying a style and can that infringe?

AI vs. infringement

Pastor: Is this a current problem?

MacKernan: A couple of years ago the answer might have been no — but now it is — yes. The first lawsuits are already filed — Andersen v. Stability AI, in which artists have brought a class action lawsuit over an AI’s creation of works “in the style of” a certain artist and Getty Images v. Stability AI over AI’s use of photos in Getty’s huge photo-library to create works.

Meanwhile, a few weeks ago the European Union proposed new copyright protections against the same sort of uses of existing works to train AI agents, which led some of the AI companies to threaten to leave the European Union. But the content owners are really upset. They see the devastation of press-advertising revenues from web-content scraping and are determined to stop something similar from happening to them.

Pastor: And what about patents?

MacKernan: AI’s been used a lot for molecular modeling — directed carefully, it’s just an inventive tool, but not a co-inventor, at least in the United States and Europe. But, suppose I ask the AI agent in very general terms to design a molecule or a device for me that does something very specific, such as having a particular therapeutic effect. And the AI agent uses information it gathered from trawling through publications on say Scorpus, PubMed, ScienceDirect, or worse, the USPTO’s website or European Patent Office, or it creates some electronic solution based on IEEE Xplore. It’s not an inventor, but is its solution infringing, and how do I know?

Watch this space. First, remember infringement is different from creating and owning IP. Second, there are some new businesses proposing to use AI tools to search for infringement of the millions of patents in force. And then there’s AI-assisted software development, using millions of existing code patterns, which could create issues under both copyrights and patents. Using AI to create databases is problematic because European law protects databases as a form of IP. Using it to design clothing and other objects is tricky, because European Registered Design protection is much tougher than US Design Patents. And then, you have all the data protection issues…

Pastor: It looks like we are in for a bit of a wild ride, and one where the legal outcomes could be very different between the United States, Europe, and Asia. But those are topics for another day.