CHEAT SHEET

- Assessments. Depending on their objectivity, arbitrator assessments can improve the quantity and quality of information about arbitrators.

- Arbitratorintelligence.org. This nonprofit venture is collecting quantitative feedback from counsel and other users through surveys about key features of arbitrator decision making, such as case management, evidence taking and awards.

- The arbitrator preappointment interview. This is another opportunity for corporate counsel to obtain information and perform due diligence on the quality and capability of a potential arbitrator.

- Party-appointed arbitrator on tripartite arbitration panels. There are critics who believe the unilateral selection of party arbitrators endangers the integrity of the arbitral process. The resolution of this issue may influence how arbitrators are selected in the future.

Major corporations’ use of binding arbitration to resolve commercial disputes has reached a critical juncture. Recent surveys of corporate counsel reveal a lack of satisfaction with commercial arbitration. One significant concern is corporate counsel’s apparent lack of confidence in, and disappointment with, US and international commercial arbitrators. For those who support binding arbitration, this trend is troublesome given that one key advantage of domestic and international commercial arbitration is the possibility for conflicting parties to participate in the selection of an arbitrator (which some would argue is one of the most important decisions in the arbitral process). This article focuses on a few of the more significant concerns from the perspective of corporate counsel in selecting an arbitrator for commercial arbitrations. It relies on four leading surveys of domestic and international dispute resolution practices used by major corporations. It also highlights potential ways to overcome these concerns and, therefore, create a more positive and satisfactory experience with the arbitral process.

US dispute resolution practices by Fortune 1000 corporations were first documented in a 1997 survey and again in 2011 by Cornell University’s Scheinman Institute on Conflict Resolution, the Straus Institute for Dispute Resolution at Pepperdine University School of Law and the International Institute for Conflict Prevention & Resolution. The 2011 survey results were compared with the results of the 1997 survey to identify key trends in corporate dispute resolution practices and obtain current information on practices not widely used at the time of the first survey. Over 600 Fortune 1000 corporate counsel were surveyed in 1997, and 368 were surveyed in 2011.

Similarly, international corporate dispute resolution practices were documented by Queen Mary University of London and the global law firm White & Case by collecting questionnaires from 136 in-house counsel in 2010 (2010 Queen Mary/White & Case Survey) and 710 in-house counsel, private practitioners and arbitrators in 2012 (2012 Queen Mary/White & Case Survey).

The responses of corporate counsel to questions about the selection of arbitrators in domestic and international commercial arbitrations are of particular interest. For domestic commercial arbitrations, a third (34.2 percent) of Fortune 1000 corporate counsel in 2011 revealed a “lack of confidence in third party neutrals” to justify their decision to avoid arbitration. The percentage was even higher in 1997 (48.3 percent). Nearly half of Fortune 1000 corporate counsel were concerned that arbitrators may not follow the law or rules in commercial arbitrations (48.6 percent in 1997 versus 44.1 percent in 2011). Half of respondents also expressed the concern that an arbitrator might issue a compromise outcome, also known as a split-the-baby award (49.7 percent in 1997 and 47 percent in 2011).

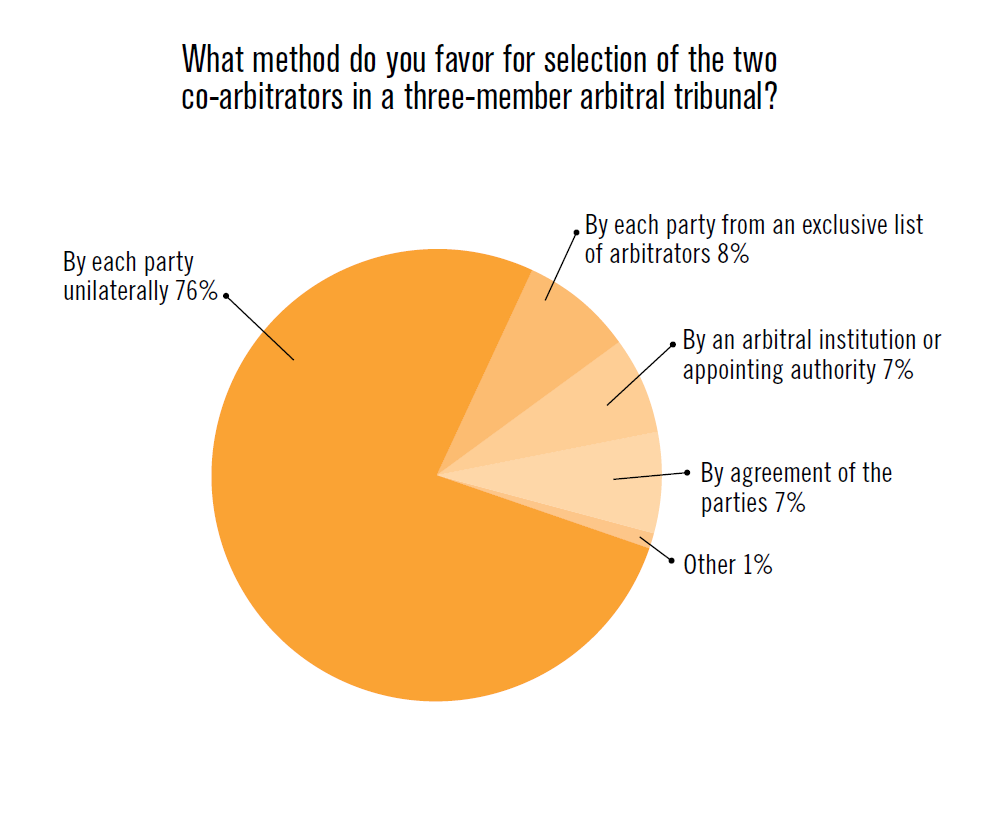

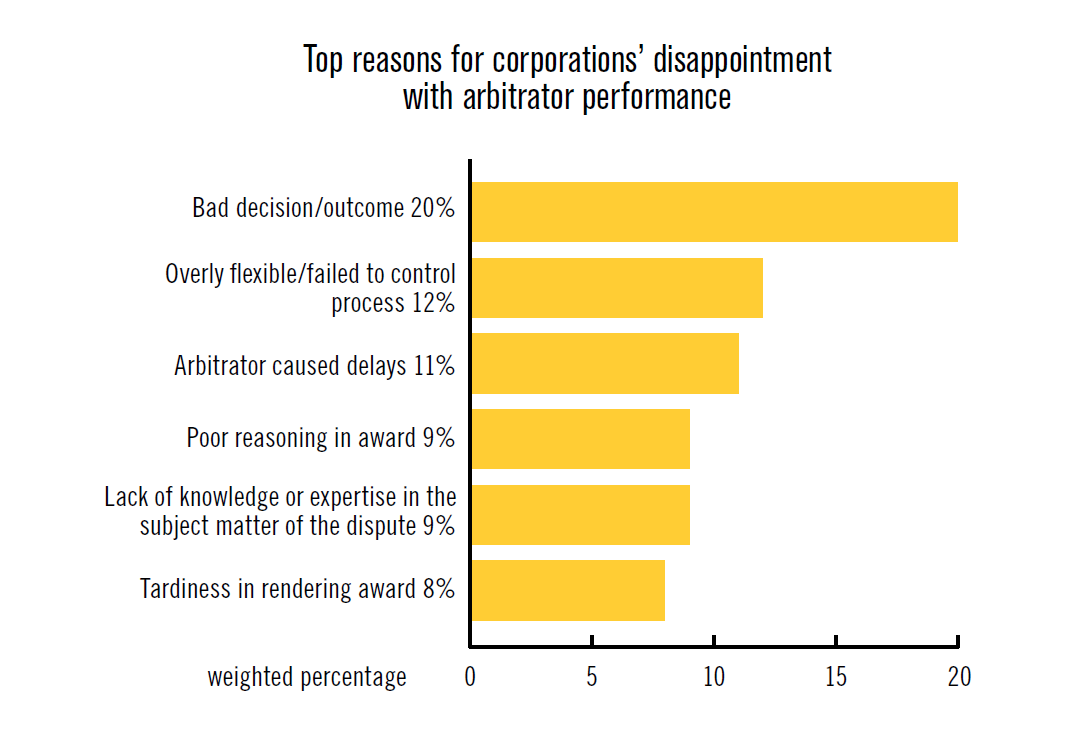

These results are similar to those surveyed on international commercial arbitration practices. In the 2010 Queen Mary/White & Case Survey, half of the respondents were disappointed with arbitrator performance. The top reason given was a “bad decision or outcome” followed by the arbitrator’s management of the arbitral process, that is, the arbitrator was excessively flexible or failed to control the process. Sixty-eight percent of respondents did not have sufficient information to make an informed selection of an arbitrator independent of input from external counsel. In 2012, respondents believed that arbitral tribunals unnecessarily split the baby in 17 percent of their cases. Additionally, a significant majority of respondents (76 percent) preferred the party selection appointment of two co-arbitrators in a three–arbitrator panel (tripartite panel). Although this is the current practice, some critics have called for an end to unilateral party appointments given the concern that a party appointed arbitrator may seize a quiet advantage for his or her party and upset the core arbitral benefits of impartiality and neutrality.

In reviewing these results, three concerns appear: First, corporate counsel are concerned about the quality and capability of arbitrators; second, they lack sufficient information about an arbitrator to make a knowledgeable selection; and third, respondents do not appear particularly concerned about the unilateral party selection of arbitrators, which, as some suggest, could endanger the integrity of the arbitral process. In response to these concerns, the first part of this article will explore various strategies for encouraging access to information about arbitrators and improving, overall, the perceived concern about the quality and capability of arbitrators. We will consider written feedback by parties in the form of a performance assessment; an online, nonprofit venture called arbitratorintelligence.org, which is increasing and equalizing access to critical information about arbitrators; and the practice of the arbitrator preappointment interview. The remainder of the article will then explore the lively debate about unilateral party appointments of co-arbitrators and whether such appointments can preserve the arbitral benefits of impartiality and neutrality. The outcome of this debate could shape how arbitrators are selected in the future.

Arbitrator assessments

It is not surprising that corporate counsel have complained about the lack of information about arbitrators. Except for a list of names and biographies, arbitration institutions provide very little information about arbitrator candidates. Users may also find information through word of mouth or professional websites, but again, this information is generally limited to curricula vitae. Given that it is nearly impossible to glean the predilections of arbitrators, biographies generally are insufficient to make one of the most important decisions in the arbitration process–arbitrator selection.

To increase information about arbitrator candidates, one suggestion is the completion of an assessment form by the parties describing the arbitrator’s performance and overall satisfaction with the arbitral process. According to Dr. Thomas J. Stipanowich, the William H. Webster chair in dispute resolution, professor of law and academic director of the Straus Institute for Dispute Resolution at Pepperdine University School of Law, the assessment “might contain information provided by the arbitrators themselves (including detailed information on breadth and depth of experience, case management philosophy, and list of previous arbitrations without the name of the parties), information provided by arbitral institutions for whom the arbitrator conducted cases (including resolution times, arbitration costs, and the role of the arbitrator), and feedback by parties regarding the arbitrator’s performance.” In the 2010 survey, corporate counsel were asked what could be done to improve information about arbitrators. Similarly, corporate counsel proposed, among other things, “a public rating system for arbitrators, published awards and published information about the enforcement of awards (if not protected by confidentiality), information available from institutions about arbitrators on request, more specific information about duration and costs, template CVs and an independent manual of available arbitrators.” Public rating systems already exist for lawyers (see avvo.com, for instance) and, given that many arbitrators are also lawyers, a similar rating or assessment tool would not be unfamiliar.

Could arbitrator assessments improve the quantity and quality of information about arbitrators? Potentially, but it will largely depend on the quality of the assessment, its overall objectivity and the number of assessments carried out on the potential arbitrator. Armed with this information, corporate counsel might feel more comfortable about the quality and capability of the arbitrator and, likewise, the quantity of information available to make a knowledgeable selection.

The nonprofit venture– arbitrator intelligence

One current strategy has been proposed by Catherine Rogers, a professor at Penn State Law and Queen Mary University of London, who recently launched Arbitrator Intelligence, www.arbitratorintelligence. org, a nonprofit venture that “aims to promote transparency, fairness, and accountability in the selection of international arbitrators by increasing and equalizing access to critical information about arbitrators and their decision making.” According to its website, Arbitrator Intelligence is collecting quantitative feedback from counsel and other users through surveys about key features of arbitrator decision making such as case management, evidence taking and awards. The project promotes itself as the first of its kind to aid a user in the arbitrator-selection process, as most information about arbitrators is developed through personal inquiries and by word of mouth. The first phase of the project collected 100 previously unpublished arbitrator awards. Subsequent phases seek to develop more information about arbitrators, including various forms of empirical data and feedback from parties. When last viewed, 878 awards (published and unpublished) had been contributed.

The arbitrator preappointment interview

The arbitrator preappointment interview is another opportunity for corporate counsel to obtain information and perform due diligence on the quality and capability of a potential arbitrator. The 2012 Queen Mary/White & Case Survey considered the appropriateness of preappointment interviews, and 86 percent of respondents regarded preappointment interviews with potential arbitrators to be appropriate or sometimes appropriate. As with hiring an employee, the preappointment interview aids in assessing an arbitrator’s background and experience, skills, personality, case management practices and views on the adherence to legal standards. The arbitrator preappointment interview depends largely on the cooperation of the potential arbitrator, and some arbitrators may refuse to grant one.

The more difficult issue for corporate counsel is not whether to use a preappointment interview but whether there are any limits on the types of questions that can be posed to an arbitrator candidate. There is little consensus on what questions should be permitted. In their article “Practical Guidelines for Interviewing, Selecting and Challenging Party-Appointed Arbitrators in International Commercial Arbitration,” Doak Bishop and Lucy Reed suggest the following useful questions and subjects for the preappointment interview: (1) the identities of the parties, counsel and witnesses; (2) the estimated timing and length of hearings; (3) a brief description of the general nature of the case sufficient to allow the candidate to determine whether he or she is competent to decide the dispute, has disclosures to make and has the time to devote to the matter; (4) the arbitrator’s background, qualifications and resume; (5) the arbitrator’s published articles and speeches; (6) any expert witness appearances of the arbitrator, including positions taken; (7) any prior service as an arbitrator, including decisions rendered (subject to any confidentiality requirements); (8) whether there is anything in the arbitrator’s background that would raise justifiable doubts as to his or her independence or impartiality and any disclosures that the arbitrator would need to make; (9) whether the arbitrator feels competent to determine the parties’ dispute and (10) the availability of the arbitrator (whether he or she can devote sufficient time and attention to the parties’ dispute in a timely manner).

One subject to consider in a preappointment interview is the arbitrator’s skill in case and hearing management. Arbitration has been criticized for its tendency to simulate a court case with a rising number of excessive disclosure requests and inappropriate motion practice that does little to support the key benefits of arbitration, such as improved efficiency and economy. Therefore, it is no surprise that an arbitrator’s failure to control the arbitral process is considered one of the top reasons a party is disappointed with an arbitrator’s performance. Complicating this matter further (at least in the United States), arbitrators are entitled to grant equitable relief under many US-based arbitration rules, and therefore “[t]he inclinations of prospective arbitrators are extremely important in gauging the extent to which a [potential arbitrator] may be inclined to look past legal technicalities and apply equitable concepts of fairness.” Given that counsel’s arbitration strategy and case presentation is strongly affected by an arbitrator’s views on procedural matters, the arbitrator preappointment interview is an invaluable opportunity.

In his article “Due Diligence in Arbitrator Selection, Using Interviews and Written ‘Voir Dire,’” Jeffrey P. Aiken suggests not only posing a series of written questions about case management to the arbitrator candidate but soliciting interviews with attorneys who have arbitrated before one or more of the potential arbitrators. Aiken includes a sample list of useful questions in his article; in general, counsel should elicit information about the arbitrator’s temperament, style and approach to decision making and the hearing. With respect to style, it would be useful to know if the arbitrator is laid back or proactive. For example, does the potential arbitrator engage with discovery issues only when requested to do so by one or both parties, or is he or she more likely to engage without a prompt? In terms of motions practice, does the arbitrator candidate entertain motions only where they present a reasonable possibility of streamlining or focusing the arbitration? With regard to the hearing, counsel might ask if the potential arbitrator examines witnesses or counsel and whether he or she requires strict adherence to witness and exhibit lists. In addition, one might ask whether written witness statements in lieu of oral testimony (common in international arbitrations) or other evidence presentation techniques were used to make the hearing more efficient.

Additionally, corporate counsel concerned with the time and cost of arbitration might select arbitrators who are committed to protocols or principles that promote efficiency and a cost-effective arbitration. The College of Commercial Arbitrators has published protocols for expeditious and cost-effective commercial arbitrations, and Professor Stipanowich has proposed arbitrator principles aimed at arbitrators committed to promoting efficiency in the arbitral process.

Above all, parties want good judgment in an arbitrator, and according to Reed this requires both art and science. The art “lies in intuiting whether and when witnesses are telling the truth, in perceiving the human stories underlying a business dispute, in crafting an award with the right reasoning and the right amount of reasoning. The science of arbitral decision-making lies in rigorously assessing the evidence, methodically finding the relevant material facts, identifying the governing law, applying that law to the facts, and … steadfastly resisting the preconceptions and premature judgments to which we are all prone” (emphasis added). Arbitrators are, after all, human, and even highly experienced adjudicators are subject to preconceptions and cognitive biases (for example, the anchoring effect, hindsight bias, cultural effects and extremeness aversion). Could the prehearing appointment interview serve to probe a potential arbitrator about his or her ability to resist cognitive biases? Expanding the preappointment interview into a potential arbitrator’s personal background would be seen by many, particularly arbitrators, as inappropriate. But, if permitted, a social scientist (or jury consultants) could help counsel “bring an understanding of human nature and ability to discern likely reactions which can be a useful additional input into the process of considering prospective arbitrators.” However, as one scholar has commented, “implicit bias, such as subconscious, cognitive or cultural bias, is extremely difficult to prove and should not be the concern of law.”

Party-appointed arbitrators on tripartite arbitration panels

The final section of this article concerns the ongoing debate about commitment or assimilation/confirmation bias by party-appointed arbitrators on tripartite arbitration panels. Respondents, including corporate counsel, in the 2012 Queen Mary/White & Case Survey overwhelmingly preferred unilateral appointment of co-arbitrators on tripartite arbitration panels. Yet there are critics who believe the unilateral selection of party arbitrators endangers the integrity of the arbitral process. The resolution of this issue may influence how arbitrators are selected in the future and, curtailing this freedom, could influence whether corporate counsel choose commercial arbitration over other forms of dispute resolution.

Jan Paulsson, the Michael Klein Distinguished Scholar Chair at the University of Miami School of Law, is critical of the unilateral party-appointment selection process. According to Paulsson, the appointment of unilaterals creates a moral hazard because the “insistence on a ‘right’ to name ‘one’s own’ arbitrator has more to do with the hope that the nominee will share one’s own prejudices rather than both sides’ values.” Martin Hunter sums up the issue nicely: “[W]hat I am really looking for in a party-nominated arbitrator is someone with the maximum predisposition towards my client, but with the minimum appearance of bias.” Given that the neutrality and impartiality of arbitrators are foundations of the arbitral process, this issue begs clarification.

What is the reason for corporate counsel’s overwhelming desire to select an arbitrator on tripartite panels? Is it because a party-appointed arbitrator might share their view of the merits of the case and persuade the two other arbitrators? Or is it because the parties lack trust in the ability of the arbitral institution to choose qualified and capable arbitrators for them? Or are other issues at stake?

One option is to ask the arbitrators if they feel constrained or biased. The CCA/Strauss Institute surveyed arbitrators on this issue and others. The finding: “[T]he great majority of experienced arbitrators (88.9 percent) perceive that at least some arbitrators selected unilaterally by a party will be predisposed toward the party that appointed them. A sizable amount of respondents — 27.3 percent — believe this happens at least half the time.” These results should give one pause.

Paulsson proposes a default rule where the neutral arbitral institution appoints the arbitrators whenever the parties are unable to either jointly nominate the entire tribunal or expressly stipulate to unilateral appointments. Paulsson makes two other suggestions: (1) joint selection by the parties of the presiding arbitrator and letting him or her choose the two co-arbitrators in a tripartite panel or (2) the opportunity to veto the opposing party’s unilateral appointment. There are other options, too: The parties could unilaterally identify potential arbitrators to the arbitral institution for inclusion in a list that is offered to the parties (which removes reliance on the arbitral institution’s list of arbitrators), then proceed to a blind appointment process; or the parties could jointly conduct interviews of potential arbitrators identified from a list prepared by the arbitral institution that is compiled using the preferences and needs of both parties; or each party develops a list and chooses an arbitrator from the opposing party’s list of potential arbitrators. There are numerous possibilities. Nevertheless, the above survey results and criticisms of the party-appointment process by Paulsson and others suggest that this is an area of real concern for parties in both domestic and international arbitrations.

Given that the debate about the unilateral appointment process cuts to the heart of the fundamental norm in commercial binding arbitration, that is, an independent and impartial tribunal, further discussion of this matter will likely continue within the arbitral community. At the root of this issue lie these fundamental questions: Is there a benefit if arbitrators owe equal loyalty to the parties, or is unilateral appointment necessary for the parties to trust the arbitral process and respect the award? Likewise, the debate concerning the efficacy of the arbitrator selection strategies will evolve over time and concern, in part, the following questions: Will the arbitral community limit or expand the nature and scope of questions posed to a potential arbitrator by the parties during an arbitral preappointment interview? Should those responses be recorded and shared with the opposing party? Will arbitrator assessments improve the quantity and quality of information used by counsel in selecting an arbitrator? It will be challenging to reach a consensus. Yet answers to these questions will help strengthen the role and perception of binding commercial arbitration particularly among disputing parties located in the United States. Likewise, it will help reinforce the aphorism about arbitration that the reputation and acceptability of the arbitral process depend on the quality of the arbitrators.

Further Reading

1 Stipanowich and Lamare, Living with “ADR”: Evolving Perceptions and Use of Mediation, Arbitration and Conflict Management in Fortune 1,000 Corporations, 19 Harv, Negotiation L. Rev. 1, 23, 26 (2013); Pepperdine University Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2013/16. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2221471 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2221471.

2 Queen Mary University of London & White & Case, 2010 International Arbitration Survey: Choices in International Arbitration, Introduction; Queen Mary University of London & White & Case, 2012 International Arbitration Survey: Current and Preferred Practices in the Arbitral Process, Introduction.

3 Stipanowich and Lamare, Living with ADR at 51 and 52.

4 Queen Mary University of London & White & Case, 2010 International Arbitration Survey: Choices in International Arbitration 26 and 27.

5 Queen Mary University of London & White & Case, 2012 International Arbitration Survey: Current and Preferred Practices in the Arbitral Process 5 and 38.

6 Jeffrey P. Aicken, Due Diligence in Arbitrator Selection: Using Interviews and Written “Voir Dire,” Dispute Resolution J., May/July 2009 at 30.

7 Thomas Stipanowich, Reflections on the State and Future of Commercial Arbitration: Challenges, Opportunities, Proposals (November 4, 2014), 55 and 56. Columbia American Review of International Arbitration, Forthcoming; Pepperdine University Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2014/29. Available at SSRN: ssrn.com/abstract=2519084.

8 Queen Mary University of London & White & Case, 2010 International Arbitration Survey at 28.

9 See www.arbitratorintelligence.org (last visited on March 18, 2015).

10 Queen Mary University of London & White & Case, 2012 International Arbitration Survey: Current and Preferred Practices in the Arbitral Process 6.

11 Doak Bishop and Lucy Reed, Practical Guidelines for Interviewing, Selecting and Challenging Party-Appointed Arbitrators in International Commercial Arbitration 47.

12 Aiken, Due Diligence in Arbitrator Selection: Using Interviews and Written “Voir Dire” at 31.

13 Id. at 32.

14 See Stipanowich, Reflections on the State and& Future of Commercial Arbitration; Challenges, Opportunities, Proposals at 81.

15 Lucy Reed, Arbitral Decision-Making: Art, Science or Sport?, The Kaplan Lecture 2012 2 – 3. A.

16 Edna Sussman, Arbitrator Decision Making: Unconscious Psychological Influences and What You Can Do about Them, 24 Am. Rev. of Int’l Arb. 487, 511 (2013).

17 Stavros Brekoulakis, Systemic Bias and the Institution of International Arbitration: A New Approach to Arbitral Decision-Making, 4 J. of International Dispute Settlement 553, 556 (2013).

18 Jan Paulsson, Must We Live with Unilaterals?, 1 ABA SIL Newsletter 1, 5 (2013).

19 J. Martin Hunter, Ethics of the International Arbitrator, 53 Arbitration 219, 223 (1987); cited in Bishop and Reed, Practical Guidelines for Interviewing, Selecting and Challenging Party-Appointed Arbitrators in International Commercial Arbitration at note 2.

20 Stipanowich, Reflections on the State and Future of Commercial Arbitration; Challenges, Opportunities, Proposals at 64.

21 Paulsson, Must We Live with Unilaterals? at 5 and 8.

22 Edna Sussman, The Debate: Unilateral Appointment of Arbitrators, 1 ABA SIL Newsletter 1, 3-4 (2013).

23 See Bishop and Reed, Practical Guidelines for Interviewing, Selecting and Challenging Party-Appointed Arbitrators in International Commercial Arbitration at 1 and note.