In the fourth edition of his definitive guide to corporate culture, Organizational Culture and Leadership, Edgar Schein asserts that there are three levels to culture:

- Artifacts:

- Visible and touchable structures and processes; and,

- Observed behavior.

- Espoused beliefs and values:

- Ideals, goals, values, aspirations;

- Ideologies; and,

- Rationalizations.

- Basic underlying assumptions:

- Unconscious, taken for granted beliefs and values.

In Schein’s framework, basic underlying assumptions are the primary cultural driver in any organization. This observation has significant implications for those of us interested in building and sustaining strong ethical cultures in corporations. It suggests that our starting point should be to understand what our business leaders really think about pursuing an “ethical” business model.

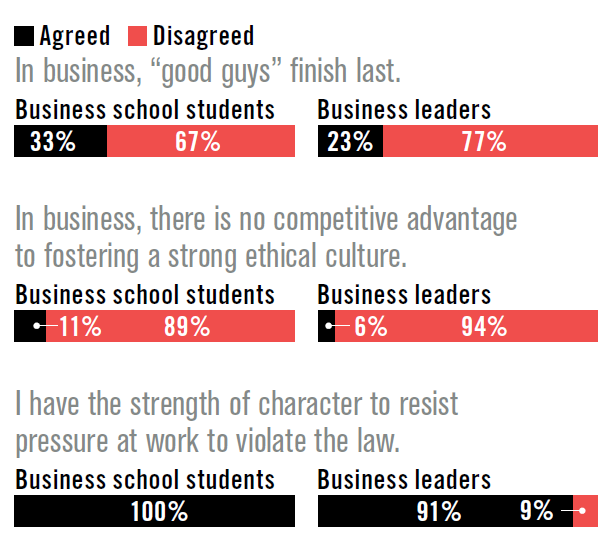

Recently, as a lead-in to a lecture entitled “Building and Sustaining a Strong Ethical Culture,” I used audience response devices to conduct an unscientific survey of business school students and business leaders to seek such an understanding. The results of these two surveys showed:

Given the relatively small sample size and the uncontrolled way I deployed these surveys, I don’t think it is appropriate to read too much into these results. However, they do provide significant food for thought. First, they reveal that a significant fraction of business professionals may believe that behaving ethically will put both them and their firms at a competitive disadvantage. When making important business decisions, those who share this belief may feel as though they must choose between an economic penalty for unethical behavior or breaking the rules to win. Despite such a belief, presumably, “ethical” business leaders would choose to play by the rules and forego perceived economic advantages of doing otherwise. However, beliefs evidenced in the fourth survey question might lead business leaders in the opposite direction.

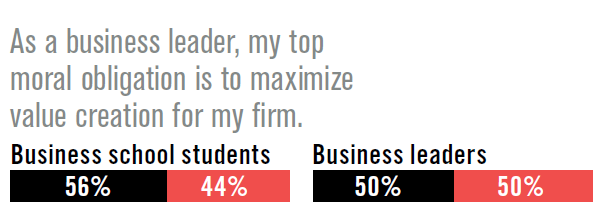

Over one half of those surveyed stated that their “top moral obligation” is to “maximize value creation” for their firm. Those who truly believe that value creation trumps all other moral obligations may rationalize their use of unethical business practices to achieve financial targets. This mindset may be, and likely is, a root cause of many corporate scandals in which “good people” make bad decisions.

Second, the survey participants’ near unanimous belief that they have “the strength of character to resist workplace pressures to violate the law” reflects a widespread overconfidence. Numerous psychological studies have demonstrated that social pressures have a surprisingly large impact on individual behavior.

In light of these observations, the following are some thoughts about what we might do in an attempt to influence our business colleagues’ underlying assumptions about pursuing an ethical business model:

Make the business case for an ethical business model

When making the business case for an ethical business model, it is important to stipulate that cheaters can and do win — at least in the short term. Engaging in unethical business practices such as swindling customers, paying bribes, and colluding with competitors can, and often does, result in financial gain. Moreover, being “good” does not guarantee success. However, there is substantial data showing that firms with strong ethical cultures maximize their opportunities for achievement.

Help your business colleagues get their priorities straight

Take steps to help your business colleagues understand that their top moral obligation is not to “maximize value creation.” Conduct self-discovery workshops that showcase how moral obligations trump the obligation to turn a profit.

Sensitize your business leaders to the power of social pressures

Awareness is the best protection against our vulnerability to social pressures at work. Share the work of Milgram, Zimbardo, Ash, and others who have demonstrated that we are not as resistant to group pressure as we’d like to think. Conduct workshops where business leaders define ethical lines and strategize how they will resist pressures to violate shared standards.

Don’t expect quick results. At the conclusion of my lecture, I made my best pitch for pursuing an ethical business model then re-polled the students and business professionals. The results were not encouraging. I failed to make any headway with the business school students and only changed a few minds with the business leaders.

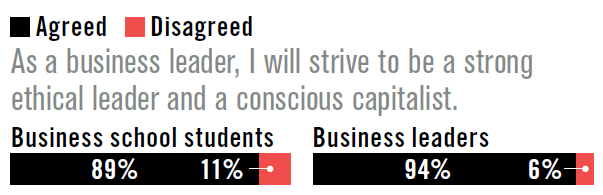

However, I did see one glimmer of hope in the last survey question.

If such sentiments are this widespread, our job in advocating ethical business practices may not be as difficult as we might fear.