Behind-the-scenes

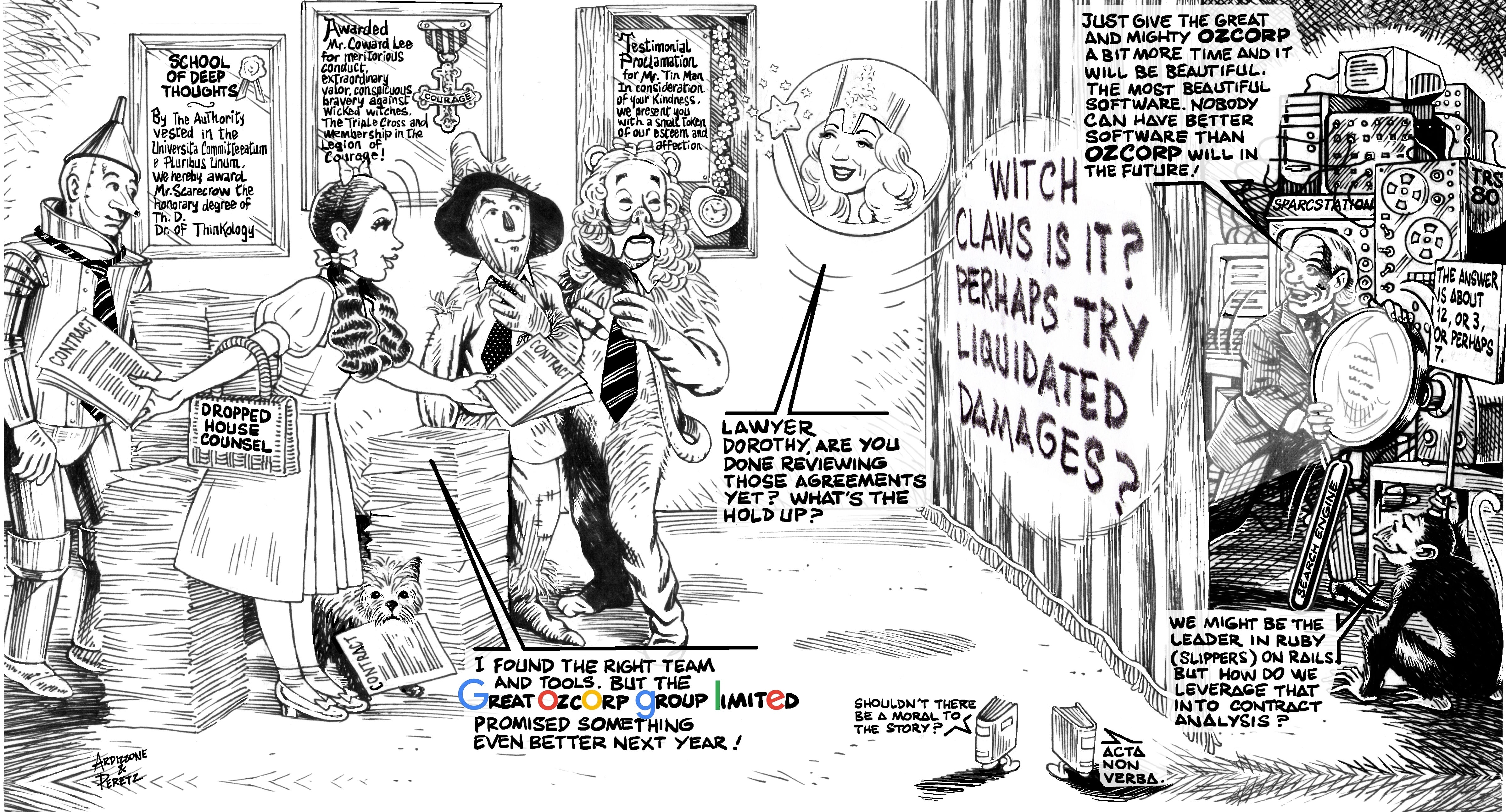

As GCs of high growth companies with limited legal headcount, we have seen the tremendous force multiplier that technology can bring to the law department. Unlike many software purchasers, however, we have also seen what goes on behind-the-scenes in tech sales because we have worked for companies that produce and sell enterprise software.

There is often a major disconnect between how technology is marketed and what is actually delivered. The goal of this article is to help you become a savvier consumer of technology for your law department.

The FUD problem

People who work in the software industry are familiar with a marketing tactic: FUD, or Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt.

In many industries, large players will do whatever it takes to keep out more innovative upstarts. The software field is no exception. A popular strategy for incumbents is to market the promise of forthcoming technology that does not quite exist, thereby sowing uncertainty and doubt in the mind of customers considering a competitive option and fear among would-be innovators. Often this strategy works perfectly for the incumbent, at the expense of the ever-waiting customer, who ultimately receives either a subpar product offering or perhaps something so soft that it should be named vaporware rather than software.

Companies that wait for a promised future product from the giant incumbent are betting that the incumbent somehow possesses superior skills at solving problems due to its budget and the market share of its legacy offerings. A look behind the curtain often reveals this as pure fable. The larger the company, the more it typically struggles to innovate beyond incremental improvements to its core offerings. This reality is demonstrated by the incessant stream of acquisitions in the technology industry, where the large players need to reach outside their own company to win outside their core business.

Large companies need to buy upstarts to win in new product areas because everyone working at the large company knows that their only path to career advancement is to focus on the existing core offering. Look no further than the 225+ tombstones in the Google Graveyard to see what ultimately happens to new initiatives by big companies. By contrast, the startups are laser-focused on something new without the distractions of maintaining a legacy code base and a giant infrastructure of sales and marketing personnel clamoring for release 3.7.1 of the core product or service.

You see this dynamic play out regularly: Facebook buys Instagram, despite surely having enough engineers to make its own. Google buys Youtube, despite having a war chest to make its own online video service. Oracle buys Netsuite, despite having already built its own financial services offerings. And Salesforce buys Slack to get into companywide messaging. These acquisitions occur because large companies are often great at sales and marketing, not at innovating outside their core existing products.

The hidden cost of FUD is higher than you think

The next time you are told that you should wait on a key software purchase because some giant company will soon release its own version of the offering, be very skeptical. At best, you may (eventually) receive a subpar offering. Essentially, you are buying FUD at the same time your competitors may be embracing new technology that is on track to become the future industry standard.

As an in-house attorney, your foremost concern is to produce results for your clients right now. Waiting for a large software vendor to deliver something more substantive than vaporware can be a much higher cost than you would expect because you are wasting months, or possibly years, of time. The cost of missing an auto-renewal date on a contract can be exorbitant. A delay in sales due to a misplaced request for legal department assistance can result in a failure to hit revenue forecasts. All these costs accrue if you buy the promise of a future product instead of a solution that works right now.

“No one got fired for buying IBM”

This popular phrase has been parroted over the years by many individuals responsible for purchasing in large organizations. It suggests that there is both personal and professional comfort in working with “traditional,” “familiar,” and large organizations. In practice, the specialty of these large vendors is that they employ individuals whose primary sales strategy is to build long-standing personal relationships with buyers and, thus, make it difficult for customers to “betray” these well-known account managers by looking elsewhere for better products or solutions.

Comfort with your long-time account representative is not likely the best predictor of success when selecting new technology. In fact, falling into the trap of continuing to blindly rely on a large, slow-moving vendor is often more dangerous than working with an innovative, lesser known new entrant. The new entrant is betting on its product and technological expertise to earn its stripes, while the larger vendor is more likely offering a combination of older generation technology accompanied by a guilt trip if you bypass them.

A key advantage of working with innovators and newer software companies is that many adopt a “lean startup” philosophy of working tirelessly with key customers to ensure that their product meets the needs of early adopters through rapid-fire iterations tailored to customer needs. The new, focused vendor is more likely hell-bent on finding a solution that meets your immediate needs because they value your feedback and want to build reference accounts. The result for your organization can be a relatively quick and easy win, which is critical for high-performance organizations where it is the outcome (not the selection process nor the choice of software) that will dictate whether or not a software implementation is deemed successful.

And contrary to popular belief, people have, in fact, been fired for hiring IBM.

Show, not tell

With the creation of the worldwide web, we were all introduced to the concept of a hyperlink, which connects an image or text to something else. Long before the web, the technology industry has boasted of a near homonym: the Hype-link. The Hype-link is a strategy used by software vendors to promise an amazing future solution based on yet-to-be commercialized technology.

Those who invest in tech know that hype is often not matched with reality. Venture capital investor Peter Thiel observed that “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.” Remember the introduction of the Segway scooter? The Guardian recalls the hype at the time that it would revolutionize “urban transportation and design, reduce the West's overdependence on Middle East oil and have a more profound impact on humankind than the development of the personal computer.” In reality, we received a 120-pound machine most now know from its prominent role in the movie Mall Cop.

The latest Hype-link you will hear about is artificial intelligence (AI). Cumbersome enterprise systems that relied on countless hours of expert human effort to use successfully are promising that adding AI to the system will magically make it effortless. In the legal sphere, we hear this tale about contract management systems, which historically have been empty databases that require attorneys to read every agreement, find the key terms, and type them into the contract management database to make it useful. Now vendors of these empty databases promise that their magical AI has made their systems automatic.

Could it be true? Fortunately, there is a way to find out: Ask for a trial. Demand that anyone claiming that they have added AI to their system give you a trial, using your own documents (not a canned demo), so you can assess the result. You need not worry about the veracity of Hype-links if you run your own tests. The same AI Hype-link dynamics exist in the medical realm. “Artificial intelligence has been suffering from overhype since the 1970s and 80s,” said Steven Salzberg, a professor of biomedical engineering at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. “Be skeptical and ask to see some evidence. [Technology companies] need to do more than simply assert that it works.”

Conducting a test is necessary, but not sufficient. Make sure that any trial that you conduct of new technologies uses the types of inputs (e.g., contracts, motions) that are truly representative of your day-to-day routine. If you don’t test with a wide-range of realistic inputs, you cannot assess the validity of the Hype-link. And if the vendor claims that its technology works instantly and yields the right result, insist on seeing it perform instantly.

Sometimes 90 percent is not a passing grade

After you have actually seen a new technology in action and verified that it’s not vaporware, it’s time to determine your criteria for assessing the success of the technology. Remember that tasks you need to complete for work may have a different threshold for success than the criteria you might apply to personal activities. For example, if you are an amateur athlete and someone offered you a software engine that found 80 percent of the relevant sportswear deals online, that might be good enough for you because you otherwise miss all the great bargains. By comparison, in a corporate law department, handling only 80 percent of matters without an error is unlikely to meet expectations.

Consider even a higher sounding success score: 90 percent. Imagine that a vendor offers your law department AI technology that claims to perform a task previously reserved for attorneys. Even a score of 90 percent on such a task might be a failing grade if it means your office screws up one out of every 10 leases or client agreements.

It’s not essential that AI or other technologies must be 100 percent perfect before they are deployed. It is, however, essential that you take into account the human cost of filling the gaps where the technology fails. Because the humans in your law department are attorneys and paralegals, they are expensive. In evaluating software, even with claims of high accuracy or productivity, your tests should measure the human cost of addressing the software’s inadequacies. Even software that is 90 percent correct can result in exceedingly high labor costs when you cannot figure out where the errors are located.

Unless the vendor is employing attorneys to verify all the results stemming from its technology output, the burden for such verification and corrections will be coming out of your budget. To quantify this cost, make sure your tests of new systems are based on a large enough sample of representative matters or documents for you to mirror a true working scenario. Then measure how much human effort you need to verify the results and correct errors and multiply that by the expected future workload. Quite often the total cost of the technology plus human experts together (which together is the total cost of ownership) may be far higher than you imagined.

Diversity is good, as long as interfaces are compatible

Another trap for legal departments is relying on the larger organization to provide every possible technological solution. There are countless stories of law department leaders deciding to move forward with a solution that meets its pressing needs and being subsequently told to instead consider how an existing solution within the company could be or repurposed for the law department.

This happens more often than not and is merely an extension of some of the principles outlined above where a fear of making waves with a new solution might upset a personal relationship with an existing vendor’s account executive. It is rare that a single vendor can provide a best-of-breed solution for all challenges faced by an organization.

And while the law department should arguably look to other departments to see how their best practices could be adapted for the legal department, there are certain nuances and unique characteristics of legal department work that cannot be pigeon-holed into an existing piece of software.

Unfortunately, the results of forcing a round legal peg into the square hole of software from another department is often disappointing. Despite having identified a better software solution that could be implemented and operationalized in fairly short order due to its tailoring to legal department needs, law department leaders are usually put back into the cycle of working with an existing vendor with a less-targeted offering. This leads to many coordinating meetings between the legal department, the IT department, and the vendor where they cycle through previous disagreements before inevitably sticking to the old way of doing things since it’s easier than transitioning.

In lieu of focusing on buying all solutions from a particular vendor, law department leaders should be focused on compatibility and interoperability issues. The growing prevalence of “application programming interfaces” or APIs by multiple organizations reflects the growing recognition that high performance organizations will have multiple systems from different vendors.

It is critical for these organizations to have the ability to make calls against or integrate with the API of their existing vendors (including the one that may have already captured the organization). For example, if your organization uses SAP for billing and invoicing and Salesforce for customer relationship management, it is important that you ensure that the solution that is being procured for the law department has the right hooks to be able to connect to those systems for work that will impact the sales or billing teams.

Of course, it may be the case that the best solution for you does not have the necessary interfaces as of day one. It could, however, be on the product development roadmap a few months down the line. In this scenario, it is crucial that the vendor understand in advance all the data you would like to interconnect with other systems to ensure that the forthcoming interface is broad enough.

In the contractual negotiations with the vendor, it will be important to ensure that there are low-cost exit points or the payment of liquidated damages if the promised interfaces are not delivered as promised. For example, if a new vendor does not deliver an agreed-upon interface, the contract could include an obligation of the vendor to assist you in transitioning (at no cost or minimal cost) to another vendor and delivering any data that may have been ingested into the solution during implementation. The contract could also include payment to build some temporary workarounds if needed.

Use those legal (thinking) skills

As a lawyer, you have spent years developing an ability to ask the right questions and carefully assess whether the evidence supports the claim. When buying technology, the same skills apply. You don’t need to be a deep technical expert if you utilize your critical thinking skills to cut through the hype.

Like preparing for a trial or an important negotiation, develop your requirements and objectives in advance. Gather all of the materials and examples you need to run a realistic test. Make the vendors show actual results, rather than hearsay about gauzy scenes of an amazing future. Calculate the direct and consequential damages of waiting for vaporware to finally materialize. And remember that those attorney fees can be quite high.