“Cultural and ethnic miscommunication and conflicts often arise because of our ignorance of different value priorities in different ethnic communities and cultures. [Unaware individuals] may attribute missteps to factors (e.g., personality flaws) other than cultural level factors.”

- Professor Stella Ting-Toomey, Communicating Across Cultures

Cheat Sheet

- Understanding cultural nuances. Cultural and ethnic miscommunications and conflicts in the workplace are often due to a lack of awareness of the different value priorities across cultures.

- Developing cultural intelligence. Cultural intelligence is the ability to function and relate effectively in culturally diverse situations.

- Building up your leaders. Choosing culturally intelligent leaders and employees helps to build more diverse and inclusive teams.

- Continue evaluating. Consistent assessments on how well HR and teams are maintaining cultural intelligence are part of a sound DEI strategy.

“I don’t think they are interested,” a young manager seated next to me at a recent conference observed after discussing challenges in increasing Latino representation at senior management ranks. “I’ve had three job postings up and none have applied.”

At the same conference, I learned about the experiences of two young lawyers, both of them first-generation immigrants. Though hailing from opposite ends of the earth (Nigeria and Thailand), they both bemoaned the criticism they had received when planning two-week-long vacations back home. Questions about their reliability and commitment to their jobs arose.

When I returned to the office, I was chatting with a coworker who was griping about a very vocal colleague who stuck up for her team during a performance rating calibration meeting. “She was so aggressive,” my coworker said. “She’s an angry Black woman.”

These conversations underscore the importance of understanding cultural differences and how misunderstandings can play out in the workplace in harmful ways.

What is culture?

According to Geert Hofstede, a Dutch social psychologist whose work includes groundbreaking theories on culture and cultural dimension, culture is “the collective programming of the mind distinguishing the members of one group or category of people from others.”

According to Hofstede, differences between national cultures can be measured on six axes, with each culture receiving a score between one and 100 on each axis. This is known as the six dimensions model of national culture.

Subsequent scholars then divided the world into geographic areas, or “country clusters” and identified which attributes are predominant in each area. For example, “Anglo” is one cultural area, comprising of Great Britain, Canada, the United States, and Australia. Arab, Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Confucian Asia are some other examples of country clusters.

Subsequent scholars have increased the number of axes to 10 and expanded the use of this tool to cross-cultural interactions within a nation and to consider diversity within cultures.

While there are various iterations of this scale, below is a summary of the dimensions of culture (oversimplified for purposes of brevity) drawn from Hofstede and the work of The Cultural Intelligence Center (CQC).

10 axes of culture

Individualism to Collectivism

A culture that ranks low on this axis values independence, autonomy of the individual, and self-reliance. At the other end is Collectivism, where, according to Hofstede, one’s place in life is determined “socially.” The CQC describes it as “an emphasis on group goals and personal relationships.”

Traditionally, over 70 percent of the world has emphasized collectivist values.

Cooperative to Competitive

In societies that are Cooperative, competing is not acceptable, and nurturing and caring are valued. In Competitive societies, assertiveness and wealth are valued, and people are judged based on their degree of ambition and achievement.

Low Uncertainty Avoidance to High Uncertainty Avoidance

According to Hofstede, this dimension relates to “a society’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity.” This is not about risk avoidance or the role of rules. Rather, Hofstede explains, “It has to do with anxiety and distrust in the face of the unknown, and conversely, with a wish to have fixed habits and rituals, and to know the truth.” The CQC describes it as having an “emphasis on planning and predictability.”

In High Uncertainty Avoidance cultures, security is assured through a rigid code of behavior and beliefs, and there is little tolerance for unorthodox ideas. Hofstede explains cultures that score low on this axis are “defined by more relaxed attitudes and unstructured environments with a tolerance for change and risk taking.” The CQC says societies with Low Uncertainty Avoidance place an “emphasis on flexibility and adaptability.”

Low Power Distance to High Power Distance

Hofstede says that this dimension measures “the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations and institutions (like the family) accept and expect that power is distributed unequally.”

The CQC explains individuals who score high on this axis believe “superiors make decisions” and “differences in statuses” are emphasized, whereas individuals from cultures that score lower on this axis focus on “equality and shared decision-making.”

Short-term Orientation to Long-term Orientation

This dimension measures the relationship between change and the past. According to the CQC, long-term oriented individuals value preparation for the future. They believe in persistence and sacrifice. In a short-term-oriented culture, the focus is on immediate outcomes. Quick results are expected.

Being to Doing

This axis measures the extent to which a society prefers quality of life as opposed to proactively working towards goals. This is not about work-life balance. It relates more to where people in a society derive their energy from.

Those who value Being will enjoy a lack of things to do and just experiencing the moment. Those who value Doing will be more engaged with reaching certain goals, whether for business or pleasure.

High Context/Indirect to Low Context/Direct

In High Context/Indirect cultures, nonverbal communication, tone of voice, and the context of the communication are equally important. In Low Context/Direct societies, words alone carry the thought.

Universalism to Particularism

Cultures that value Universalism have strict rules that apply equally to everyone. In cultures that score high on Particularism, the standards vary based on the relationship.

Neutral/Non-expressive to Affective/Expressive

In Neutral/Non-expressive cultures, people hide their feelings and may be perceived as unemotional and uncaring. On the other end of the spectrum in Affective/Expressive, societies share feelings and value expressiveness.

Monochronic/Linear to Polychronic/Non-linear

In the Monochronic/Linear, people focus on one thing at a time. Time is valued and work and personal life are separated. In the Polychronic/Non-linear, there is an emphasis on multi-tasking, interruptions are accepted, and work and personal lives are blended.

Cultural axes applied to country contexts

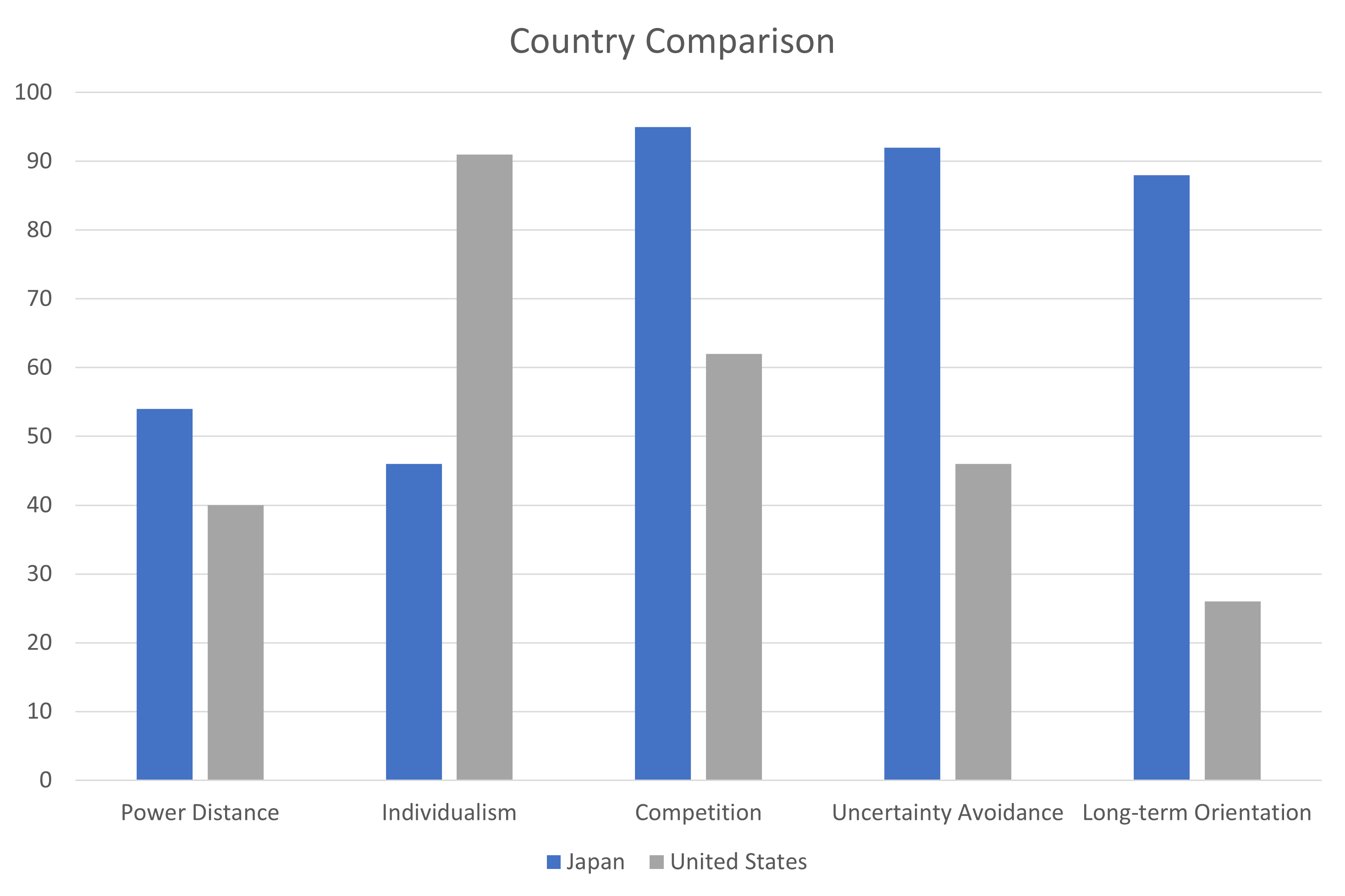

United States

In the United States, there is a dominant culture of every person for themself (91 on Individualism), superiors are accessible, and there is an emphasis on equality (40 on Power Distance).

In the dominant US culture, there is a focus on competition and achievement with winners and losers, and people live to work in order to earn more so they can show off their higher status (62 on Competition). In this dominant culture, new ideas are accepted, and freedom of expression is valued (46 on Uncertainty Avoidance), quick results are expected, and shareholders expect quarterly results (26 on Long-term Orientation).

Japan

In Japanese society, corporate decisions are frequently confirmed by successively higher members of the company (54 on Power Distance). Harmony of the group is valued more highly than individual expression (46 on Individualism).

A severe competitive drive creates a relentless pursuit of perfection and workaholism (95 on Competition). To maximize predictability, a lot of time and study ensues, and all risks are evaluated before a decision is made (92 on Uncertainty Avoidance).

In Japan, there is emphasis on investing in the future (spending, for example, on R&D even when the economy is down) based on the belief that the obligation is not to shareholders on a quarterly basis but over the long term and to the larger society (88 on Long-term Orientation).

People are individuals within a culture

This framework describes the predominant norms of a culture, based on empirical intercultural research. However, to avoid the perpetuation of stereotypes, it is important to remember there are individual and regional differences within every culture. Not every person in a particular culture has these exact values as there is diversity within cultures and among people.

This cultural dimension structure was developed to facilitate communication across nations. But it could have applicability in the workplace, not only for those who manage global teams, but also for those who manage diverse teams within one broadly diverse nation, such as the United States.

Not every person in a particular culture has these exact values as there is diversity within cultures and among people.

Might a manager who understood, without defaulting to stereotypes, how to encourage a subordinate who was reticent to appear ambitious, be more effective in developing their diverse team?

Likewise, could a manager who recognized a strong commitment to family as indicative of loyalty instead of shirking responsibility, and who knew how to differentiate passion and enthusiasm from anger or a lack of composure, be more successful in managing their diverse team?

Cultural intelligence is foundational

The need to effectively communicate across cultural chasms has already been recognized in healthcare, where life and death may hinge on the ability to effectively communicate. Educators have begun to think about it as well.

Companies must, therefore, also consider the following: How can a manager of a diverse team really be effective without cultural intelligence?

When selecting managers, organizations should be measuring not only their technical competence in their assigned functional area but also their ability to effectively manage across differences. Where lacking, a plan should be implemented to develop this competency.

What is cultural intelligence?

According to the CQC, cultural intelligence (or CQ, a trademark of the CQC) is the capability to function and relate effectively in culturally diverse situations.

The Sage Handbook of Intercultural Competence lists five specific skills, cogently summarized on Wikipedia:

- Mindfulness. This refers to “the ability to be cognitively aware of how the communication and interaction is developing.”

- Cognitive flexibility. This refers to being open to new information and differing perspectives.

- Tolerance for ambiguity. This refers to “the ability to maintain focus in situations that are not clear rather than becoming anxious.” People with this skill seek to expand their understanding rather than defend their beliefs.

- Behavioral flexibility. This refers to “the ability to adapt and accommodate behaviors” of different cultures.

- Cross-cultural empathy. This includes the ability to connect on an emotional level and engage in active listening.

The CQC compresses these skills to four competencies:

- CQ Drive is the level of interest, persistence, and confidence in multicultural situations.

- CQ Knowledge is the level of understanding about how cultures are similar and different.

- CQ Strategy is the awareness and ability to plan for multicultural interactions.

- CQ Action is the ability to adapt when relating and working in multicultural contexts.

Proficiency in all four areas is necessary to be culturally intelligent.

Culturally intelligent managers

How can an employer tell if a candidate has CQ Drive or CQ Knowledge? Here are a few preliminary indicators to evaluate during the recruitment stage:

- Has the candidate demonstrated levels of CQ Drive or CQ Knowledge via their cross-cultural experiences?

- Has the candidate spent time immersing themselves in a different culture, such as studying or volunteering abroad?

- Did the candidate grow up in or does the candidate currently live in a multicultural neighborhood?

- Does the candidate have hobbies that reflect a diverse mindset or expose them to different communities?

- Is the candidate multilingual?

Other data points may suggest more developed skills in CQ Action or CQ Strategy:

- Are the high potentials in their group demographically diverse?

- Are retention stats of all demographic groups they manage comparable?

- Who are they developing and sponsoring?

- Do their subordinates feel heard?

- Do those subordinates feel comfortable bringing their whole selves to work?

To assess the presence of a more developed CQ Action or CQ Strategy, consider asking candidates for a time when they had to adapt to a new project/boss/cultural context, such as following the merger of two divisions. Assess how they planned for the new situation and what adaptations they needed to make in order to succeed.

Interested in measuring your cultural intelligence? Receive a complimentary CQ analysis.

Finally, there are assessments of CQ, such as the assessments offered by CQC. The Intercultural Adjustment Potential Scale (ICAPS) and the Multicultural Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) are other options that have received good reviews. Read "Assessing Cross-Cultural Competence: A Review of Available Tests" by David Matsumoto and Hyisung C. Hwang in the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology for more information.

How do we develop culturally intelligent managers?

The good news is cultural competency is dynamic. While it’s not something you can master as there are too many cultures, the skills can be measured and developed.

We can develop a mindset of awareness of our own world views and humility from recognizing the limitations of those views. We can develop a curiosity about the perceptions and experiences of others, which creates empathy. We can offer opportunities to learn about other cultures and require training on cross-cultural communication.

We can promote reverse mentoring and include proficiency in these skills as a prerequisite to promotion to people leader roles. We can move from ethno-centrism, where we believe our culture is superior and evaluate other cultures based on our own standards, to ethno-relativism, where we appreciate that our culture is just one of many cultures and work to understand and accommodate those other cultures.

Does this framework promote stereotyping?

It may be tempting to say because a person has roots in a certain culture, they will think and behave in a certain way. But it is important to remember many people, regardless of ethnicity, reflect an individualized blend of dominant culture values while still retaining significant aspects of other cultural groups.

Accordingly, this framework is most helpful in promoting ethno-relativism and should not be seen as a simplistic diagnosis of how others may view the world. Knowing that differences exist and when they might be present can help us identify if a cultural disconnect is at play and impacting an interaction.

It’s important to understand that these dimensions — and the places and culture groups where they are more commonly found — are the start of the exploration, not the end. For that reason, a culturally competent manager must continue to evaluate people as they are.

Are we unfairly assessing employees against the dominant culture norm?

A second compelling question is this: Do our own HR processes unintentionally disadvantage employees whose cultural values do not reflect the dominant norms? For example, within the United States, most corporate cultures likely reflect the dominant Anglo culture.

Using that context for reference, consider the following:

How do we evaluate performance?

- Are employees from a culture that values High Power Distance (the Anglo culture values Low Power Distance) seen as not contributing, even disengaged when perhaps they are being respectful?

- Do individual sales goals or forced rankings motivate employees who share the Anglo value of Competitiveness and Individualism but disadvantage employees from a culture where Cooperation and Collectivism are more important?

- Are employees from cultures with High Uncertainty Avoidance (Anglo culture is Low Uncertainty Avoidance) seen as lacking initiative or stuck in their ways when they are being careful?

- Are employees from Polychronic/Non-linear cultures seen as wasting time and lacking focus on their assignments when they interrupt their work to acknowledge others?

- Are employees from a High Context/Indirect communication style seen as poor communicators or even indecisive?

What about assessing leadership potential?

- Are employees from a culture of High Power Distance seen as lacking the ability to lead or to make independent decisions because they are more likely to defer to their superiors than to challenge the status quo?

- Are employees who have a Long-term Orientation seen as unable to pivot when in fact they are considering the long-range implications of a decision?

- Are employees with a cultural value of Affective/Expressive communication seen as lacking executive presence?

What about during investigations of internal matters?

- Are employees with a strong sense of Particularism (the Anglo culture values Universalism) more reticent to cooperate and perhaps seen as evasive, even dishonest, when perhaps they are struggling with the conflict between personal relationships and their obligations to their employer during an investigation?

- Or as another example, is it possible that employees from a culture valuing High Power Distance were raised to believe that their superiors are always right and, therefore, are uncomfortable questioning their actions. Might they prefer to find a way for their errant supervisor to save face?

- Are employees who utilize a High Context/Indirect communication style not being heard by those who value Low Context/Direct Communication and, therefore, do not also consider nonverbal communication, tone of voice, and the context of the communication?

What about evaluating who is a team player?

- Are employees with a strong culture of Individualism seen as oppositional?

- Are employees who value Competition less likely to support DEI programs, not because they have discriminatory views but because they perceive the solution to the challenge in a different way? Or are they from a culture that values High Power Distance and might be uncomfortable rocking the boat?

While these questions were developed with the US cultural framework in mind, this analysis can also be applied to your organization’s country and cultural context.

This is not to suggest corporate expectations must change, rather that there is a need to better understand how corporate culture may be impacting some employees more than others. We need to develop strategies to account for this to ensure all voices are heard in a way that is respectful of culture.

There are entities, such as the CQC, which offer consultancies to assist organizations in assessing and tweaking their systems to mitigate the impact of cultural bias and certifications to assist HR leaders in developing this expertise in house.

This is not to suggest corporate expectations must change, rather that there is a need to better understand how corporate culture may be impacting some employees more than others.

At a minimum, we must do a better job at introducing our values, because we cannot assume that they are universally shared. We need to do a better job of explaining the why behind our values with a context that will resonate with employees in other cultures.

If equity means giving each employee what they require to succeed, as distinct from simply treating all employees in the same way, understanding how cultural values may impact the outcomes of HR processes is equity at its core.

Assess scenarios with a cultural lens

In the beginning of this article, we described three scenarios:

- A company where the Latino population was perceived as not actively seeking promotion;

- A scenario in which recent immigrants were being criticized for taking extended vacations; and

- An incident in which a manager criticized an impassioned African American coworker.

Each of these scenarios reflected a cultural challenge where cross-cultural fluency was necessary to avoid misunderstandings.

Assessing scenario one

Our company offers the opportunity for reverse mentorship, and I was recently paired with a young Latina. Troubled by the conversation I just had at the conference, I asked her whether she had any observations on why the representation of Latinos in senior management and executive leadership in US corporations generally lagged behind other demographics.

She pointed me to the "Latino Executive Manifesto" by Andres Tapia and Robert Rodriguez. Tapia and Rodriguez wrote in their book Autentico:

“Latinos must embrace ambition as an honorable intent. While maintaining humility we must not also be naive. No one is going to hand us opportunities if we are not openly seeking them. The community should celebrate those who demonstrate this ambition because we all benefit.”

She elaborated, observing that many Latinos are taught that too much ambition is a bad thing, that many in her community accepted their current position as inevitable, which, according to Hofstede are characteristics of cultures that have High Power Distance, such as Mexico.

An employee from such a culture should not be written off as disinterested in advancing. Rather there may need to be different development strategies. The current processes that require demonstration of ambition or even a requirement to publicize their desire for a promotion may not yield the diverse pipeline companies crave.

Assessing scenario two

Regarding the two lawyers who were labeled uncommitted to their jobs because of their travel plans to visit extended family in another country: Employees from Collectivist cultures are going to view family as paramount.

A manager from a different cultural viewpoint might not recognize this as a sign of loyalty or integrity, but it is. Managed sensitively, retention rates can be enhanced with this renewed perspective because such employees also tend to be loyal to their employers.

Assessing scenario three

And the “aggressive” coworker? Many Latin and Sub-Saharan cultures are Affective/Expressive cultures, and those values often present in African American and Latino communities in the United States.

But to a manager from a culture where Neutral/Non-expressive communication is the preferred mode, an individual using an expressive approach can be perceived as aggressive or perhaps even threatening when what is being expressed is passion or even enthusiasm. That passion or enthusiasm should be channeled — rather than silenced — if you want to maintain engagement.

Conclusion

If we value diversity of thought, if we value a global mindset, if we truly want to be inclusive and promote a sense of belonging, we must promote cultural intelligence as a necessary foundational skill at all levels of our organizations.

DEI, Esq. is comprised of in-house counsel who share a deep passion for diversity, equity, and inclusion. While the members, Jane Howard-Martin, Connie Almond, Olesja Cormney, Jennifer N. Jones, and Meyling Ly Ortiz, work as employment counsel at Toyota Motor North America, Inc., their views and the thought-leadership expressed are their own and not necessarily the views of their employer.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Linn Van Dyne and Tina Merry of the Cultural Intelligence Center for their input on this article. Please visit the Cultural Intelligence Center website to learn more about their programs, workshops, certifications, and multiple-languages assessments.