CHEAT SHEET

- Holistic review. View your contract review process in a holistic way that incorporates a business mindset, a storyline of how the contract fits into the relationship between contracting parties, and the changing business environment.

- Mindset. Use a flexible framework to review contracts against business risks and rewards, like potential disputes, regulatory regimes, and internal finances.

- Storyline. Place your contract review within the context of real-world relationship-building from engagement to marriage to the break-up.

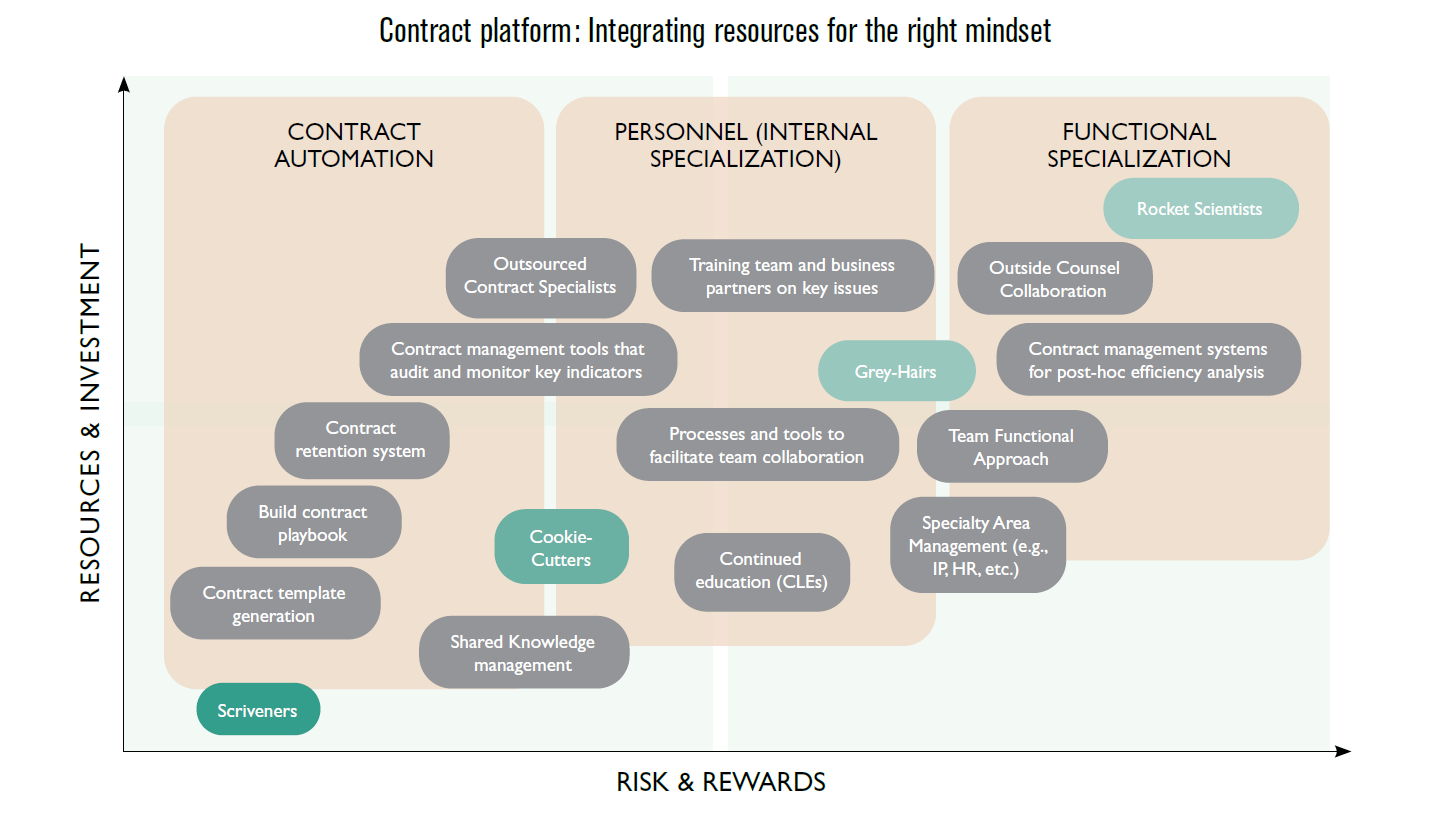

- Platform. Develop strategies for a contract platform that considers contract automation, personnel, and function specialization.

In an increasingly complex in-house legal world, amidst shifting organizational, legal, and technological approaches, one fundamental task remains for in-house lawyers: Manage the backbone of their organization’s relationships — contracts — in a strategic and efficient way. Traditionally, managing contracts was an individual and esoteric art, where lawyers or contracting specialists relied on training and experience to individually review and assess contracts on a case-by-case basis. For business clients, this was a mysterious process, subject to the whims of the lawyer reviewing the contract. Today, as with any business function in an increasingly data-driven and accessible world, the legal task of reviewing your enterprise’s contracts can be more systematic, objective, and effective, provided that legal department leaders can understand, assess, and strategize about their contracts on a macro-level — and adapt accordingly.

Corporate counsel’s measuring stick for success is not how many hours they can bill for their services, but how efficiently they can provide such service, while reducing “overhead” cost in the company’s performance and managing business risks.

Across industries and departments, businesses integrate automation and technology into operations, with promising results. Companies see higher efficiency and greater employee productivity. And employees, when properly utilized, don’t spend their days on repetitive tasks, but instead evaluate the “big picture” and perform more judgment-intensive, intellectually rigorous tasks. This has led small to large in-house legal departments as well as technology and consulting service providers to build and provide contracting tools and automated approaches. With the advent of artificial intelligence (AI) in contract management looming large, lawyers face the possibility of technology and machine-learning automating large portions of contract review and management. However, perceiving the forest from the trees and the exceptions to an algorithm’s rules will require competent, strategic lawyers.

By viewing contract review in a holistic way, your contract review team can improve outcomes. Our unique paradigm incorporates:

- Mindset: A flexible framework to review individual contracts against business specific risks and perspectives;

- Storyline: Context incorporating the real-world relationship-building between contracting parties, including the “contract engagement, marriage, and break-up”;

- Platform: Strategies for how to build effective principles for your in-house legal department to address your contracts in today’s rapidly changing world.

This new paradigm will give you a framework to improve how your team views risk/reward decisions, team resources, contract management principles, and overall contract management systems.

Contract mindset

Often, in-house legal departments — no matter the size — must wear more “hats” than firm lawyers. By contrast, a firm lawyer specializing in an area of the law may wear only one of these hats for most of her career. In-house lawyers, who must understand all aspects of their company’s business and its business relationships, may need to take into account the risks and rewards found in a multitude of areas that a contract reviewing specialist may not appreciate, such as potential disputes, compliance, business risks, regulatory regimes, operational implementation, internal finances, and communications; these factors undoubtedly complicate and may be ignored in traditional contract management. Corporate counsel’s measuring stick for success is not how many hours they can bill for their services, but how efficiently they can provide such service while reducing “overhead” cost in the company’s performance and managing business risks. The in-house lawyer must strategize and spend her time, assets, and effort where she can drive growth for the company. The firm transactional lawyer also has the luxury — or annoyance — of walking away from the results of the agreement once it is finalized. The corporate counsel, on the other hand, sits in an office next door to the chief operating officer executing the contract requirements, and eats lunch across from the salesperson attempting to meet minimums outlined therein. Thus, the firm lawyer leaves right after the engagement, and the in-house counsel stays for the entire marriage.

Each individual business relationship embodied in a contract has a different risk and reward metric associated with it. A billion-dollar merger requires a different approach from the approach used to renew an often-used, off-the-shelf software license. If a lawyer is able to assess the risk and reward of various contracts, the lawyer should adopt a mindset appropriate for the contract’s risk and reward level. An automated system may not appreciate the right “mindset” during review, whether that is by taking into account dollar volume, reputational value, or personal dynamics of the contract and parties. The mindset of contract review may be analogized on a spectrum that describes skill categories of lawyers, such as a “scrivener,” “cookie-cutter,” “grey-hair,” and “rocket scientist.” Not every agreement requires flying to the moon; a software license renewal may simply require updating the terms to reflect any changes, which is scrivener-level work.

Appropriate contract review by in-house counsel requires a variety of approaches to deal with the various types of contracts they review. Different skill levels and mindsets are appropriate for different types of transactions:

- “Scriveners” have minimal legal background or risk analysis experience. Their involvement includes transcribing terms of discussions or negotiations between business partners.

- “Cookie-cutters” are builders and users of the contract playbook or a legal forms database. They rely on encoding experience into standardized procedures that can be applied at a relatively low cost.

- “Grey-hairs” apply judgment gained from prior experience to tailor the contract to the relationship’s needs. Thus, they take a form and add a bit of value by combining their understanding with the current needs in that situation. This may be viewed as traditional “lawyering” despite the fact that there are no metrics to measure the success of one’s “grey hair.”

- “Rocket scientists” innovate, develop, and apply theoretical and empirical tools to tackle rare, new, or complex problems. Company acquisitions or complex, large joint ventures, may not only require the most skilled of lawyers, but teams of lawyers or creative solutions more rarely faced by the client.

Contract reviewers must recognize his or her mindset — which may be based upon his or her legal training, skills, or experience — when confronting a contract to review. Does the mindset match the transaction at hand appropriately? If not, does your contract review system drive your team members to approach the particular transaction with the right mindset?

Contract storyline

A contract is first an arrangement and relationship; legal professionals often forget to treat their written agreement as a living relationship with depth and continuity rather than simply words in a medium. While lawyers often spend cycles nitpicking over the dispute resolution, indemnification, or damages provisions, we ask you to consider the percentage of your contracts that actually reach that point. How many of your contracts actually fail? For example, in a mid-sized company’s legal agreement database of 1,000 contracts, perhaps only a few disputes will materialize from those contracts. In-house lawyers are also familiar with the ever-present tension between lawyer and his client on the importance of the need for detailed “grey-haired” analysis. The typical businessperson hopes to quickly execute the contract to recognize the sale or commence the project, and then immediately files it away to never have to reference it again. Conversely, the in-house lawyer’s role is to agonize over that contract, its terms, the possibilities, the potential impacts.

Our legal industry is biased towards lawyers showing their worth through their thinking in written documents. So the more we can dicker over language and provisions, the better we demonstrate our experience and expertise. While it is certainly true that in-house counsel should and do try to avoid using “problematic” contract provisions, which has been the focus of legal education today (i.e., avoiding “pitfalls” in language that cases and judges have later interpreted after businesses cannot resolve the interpretation), this “yes/no” mechanism and drafting of language can eventually be automated. Further, we have to acknowledge that lawyers cannot predict with certainty what sorts of circumstances will give rise to successful implementation or controversy, which in turn may influence the weight, importance, or application of such language. Even somewhat sophisticated business clients understand that ADR and damages provisions only become an issue if something on the front-end or midstream goes awry. In a rosy world envisioned at the start of the engagement, every party will fulfill their obligations under the contract until the project is complete or the relationship renewed.

Our new perspective, the “contract storyline,” considers in-house counsel’s unique responsibility over not just contract terms, but the entire marriage or relationship between the parties. Generally, relationships are formed, operationalized, and then terminated or renewed. For the most part, the outside lawyer lives at either end of the contract storyline. On the other hand, the in-house counsel, with their office in or near the C-suite, may experience the deeper contract lifecycle, and lives with the issues that arise during operationalization.

The in-house lawyer lives throughout the engagement, marriage, and break-up within the contract storyline. On the front-end “engagement” phase, counsel designs, drafts, negotiates the approval of the contract, ensuring the agreement reflects the meeting of the minds. To differing degrees, outside transactional counsel witnesses or assists in this stage, based on the type of contract, risk, and skill-level of the in-house lawyer or lawyers, but they may or may not have the necessary mindset going into that review. During this phase, parties are also laser-focused on certain immediately relevant provisions, such as consideration deliveries, financial covenants, and work or product deliveries. One could argue that these provisions are far more important to the financial success of your client than the “break-up” provisions, such as governing law or venue, which may never come to bear. Consider if your contract management system captures this earlier-stage data in a meaningful way and whether your functional partners recognize your contributions to the company’s bottom line by catching items with business impact, as opposed to simply outlining potential risks.

During the marriage phase, each party and its agents must understand and be able to operationalize the contract, not only to avoid either inadvertent breach or performing more than the contract demands, but to ensure each party gets what they bargained for. These terms reflect the day-to-day operations of the contract, and where your company will start to experience when the contract does not accurately reflect the meeting of the minds. Marriage phase provisions include outlining who is obligated to perform, what is the obligation, by when must the obligation be performed, where will performance take place, how is the obligation to be performed, and the how much, when, and where money or goods will be transferred.

In this phase, in-house counsel lives the words they have put on the paper. The business teams should start to ask when revenues, royalties, and license fees, are delivered against the products sold or services delivered. This is also when in-house counsel experience risk day-to-day. As such, valuable contract management systems increase awareness towards monitoring and auditing, as opposed to simply creating and retaining contracts. Sophisticated contract management systems can account for not only when certain contracts will expire and need to be renewed, but also when payments are to be made, what interest must be charged for late payments, when deliveries are due, which obligations are key, and who is responsible for ensuring they are met. However, an artificial intelligence (AI) bot will not be able to advise a client on the value of their “reasonable best efforts” performance obligation or whether “good-faith” was observed during the performance. The lawyer’s real work, in the day of contract automation, may start to become helping clients manage the delivery of goods and services in accordance with the contract terms that a scrivener or AI bot has created. Knowing your own company’s business “storyline” may enlighten your priorities on what to focus on in the engagement phase and vice versa.

If and when the relationship nears a “break-up,” business partners come rushing to the lawyers. So, lawyers managing the contract management systems should understand the frequency, type, and impact of break-ups. Certain businesses will make their business on break-ups (e.g., insurance); others will hope a break-up never comes. But, imagine a world where in a future contract management platform, the legal department can anticipate and mitigate break-ups. Through proactive partnering with clients and then monitoring of performance, we can alert the client to potential risks, finance teams to accrue for it, prepare the right outside counsel in advance of the crisis. These elements can only be addressed with deeper understanding of your break-up provisions, scenarios, and experiences, which are ingrained in your storyline and addressed in the contract management cycle.

Arguably, for your legal departments to stay ahead of the curve, we should all strive to move our teams “up” within the mindset paradigm, from scriveners and cookie cutters to grey-hairs and rocket scientists, while applying our risk/reward counseling with a storyline view of our contracts. Remember that the varying nature of your industry or business may dictate that different elements of the mindset and storyline receive greater or lesser diligence and investment. You can and will demonstrate an enhanced value add by understanding your legal team and resources and your clients’ business relationships, and by effectively managing those contracts to impact those relationships.

Contract platform

After considering your legal team’s mindset, and your business’ storylines, the next logical consideration is designing a contract management system, or “contract platform,” to adequately address risk and rewards within relationships through contracts. Our experience at a mid-sized, but mature, global business with a small legal department, was to implement our “contract platform” through proactive cooperation between lawyers and business teams, team training, systematic approaches, and technology. undoubtedly, each legal department at companies of various sizes, will face different people, budget, and technology constraints. So, thinking about the mindset and storyline within your business should lead you to consider such topics as:

- Who performs reviews of what types of contracts?

- What mindsets are applied to those types of contracts?

- How are certain contracts and review methodologies implemented and segregated?

- How can common storyline topics and concerns be institutionalized and managed more efficiently while balancing risk appropriately?

Whether you are a legal team member serving a more functional role within a larger department, or a manager of the legal function with a macro view, it benefits your team to have adequately considered these mindset and storyline perspectives. Your goal should be then to design and evolve your contract management “platform” to address your business, develop your team, and manage resources within the legal function according to the needs of your business. In the future state of contract management, in spite of the client differences, lawyers will no longer be seen as just as scriveners. Lawyers need to be at least perceived as grey-haired partners knowledgeable of relevant contracts. But lawyers will be seen as far more than that if they become rocket scientists who devise the ideal contract platforms to efficiently and cost-effectively manage their legal contracting functions. If they don’t, they’ll run the risk that contract automation takes contracting generation and management away and they become less valued.

In order to avoid becoming obsolete, demonstrate your advanced thinking by discussing and devising the appropriate contract platform for your businesses. To properly design this platform, ask and continue to ask about the following:

Your goal should be then to design and evolve your contract management “platform” to address your business, develop your team, and manage resources within the legal function according to the needs of your business.

Types of contracts

What types of contracts most concern your business and your legal team? And how do these types of contracts relate practically to your business? By understanding the functioning purpose of types or categories of contracts, you can better understand the risk and business reward of those contracts. For example, which contracts generate revenue, which mitigate competition or risk, which might preserve or create an asset, in addition to what contract might create a liability.

Legal experience and skills

Once you understand that, you can start to devise a “mindset map,” plotting where types of contracts might be addressed by what resources you have in your departments. You might ask: Are the appropriate levels of legal experience and skill being applied to the right categories of contracts? For example, are your highly skilled lawyers working on contracts that are lower on the risk scale and could be automated? Are less skilled contract specialists getting opportunities to move into a “grey-haired” position for personal development?

Client relationships

From a time-based and continuum-based perspective, is your contract management system properly taking into account the elements of your storyline? Do you have checks and balances in place, for example, to audit or monitor performance, inform business clients of “break-up” risk, so that the legal department can bring value beyond contract language and execution?

By taking a holistic and comprehensive contract management approach, your legal department can practically apply a resource-based, risk/reward-based, and business-based approach to contract management. This could allow you to set your own metrics to collect on contract workload, quantify achievements, manage on-going performance and risk, and report those performance indicators as proof of value. For example, these perspectives may influence your investment and dedication to the following elements in your contract platform:

- Personnel and training to ensure a right-sized personnel resource approach for the right legal and business risks, while informing your development, advancement, and retention goals for your team with internal training based upon actual contract mindset and storyline perspectives;

- Tools and resources to acquire and allocate the right tools and technology (e.g., contract management software, forms databases, contract playbooks, etc.) and right use of outside vendors (e.g., law firm, LPOs, outsource vendors, research vendors, data management, and consulting firms, etc.) to the right levels of your platform;

- Customized knowledge management to develop your own customized knowledge management platform for your contract management system, whether this is well-designed shared drives amongst working teams, to internal corporate SharePoint systems, to third-party solutions with your design inputs and end-goals in mind; and

- Proper processes and procedures to better collaborate within your team, guide interactions with your client, communicate with individuals who play within the platform to ensure proper performance going forward through appropriate risk and business based auditing and monitoring based upon the right mindset, storyline driven data.

By walking through and understanding your company’s own unique contract mindsets, storylines, and potential components to your platform, in-house counsel in this new technology, data, and automation-driven environment, can ensure their thinking is well beyond the traditional, less-highly operating legal function. Demonstrating your understanding of macro-business issues and environments, and your ability to envision, design and drive to a future state of your department’s contract management platform, will demonstrate tangible, understandable, measurable value, in addition to potentially ensuring the actual success of contracts, as compared to the perceived painful time and efforts spent simply crafting and executing the agreement. This value should sit squarely within your company’s legal and contracting function, as these groups will be the best positioned to monitor this data and ensure the proper business function’s awareness of key performance indicators. Let’s all shift and progress our mindsets, understand our storylines, and create our new platforms. This should be the ultimate goal for your future contract management paradigm.

References

Sophie Gould, Legal Technology: Looking Past The Hype, 168 NLJ 7814, p18 (2018).

Symposium, The Changing Role and Nature of In-House and General Counsel: Delawyering the Corporation, 2012 WIS. L. REV. 305, 314 (2012). See also Michael Guihot, New Technology, The Death of The Big Law Monopoly and the Evolution of the Computer Professional, 20 N.C. J.L. & TECH. 405, 444 (2019); Jason G. Dykstra, Beyond the “Practice Ready” Buzz: Sifting Through the Disruption of the Legal Industry to Divine the Skills Needed By New Attorneys, 11 DREXEL L. REV. 149, 177 (2018).

George G. Triantis, Improving contract Quality: Modularity, Technology, and Innovation in contract Design, 18 STAN. J.L. BUS. & FIN. 177, 186 (2013).

Triantis, supra note 5, at 186.

Steven L. Schwarcz, To Make or to Buy: In-House Lawyering and Value Creation, 33 IOWA J. CORP. L. 497, 519 (2008).

The terms “cookie-cutter,” “greyhairs,” and “rocket-scientist” were first introduced in this context during a study of professional service firms in DAVID H. MAISTER, MANAGING THE PROFESSIONAL SERVICES FIRM 4 (1993). Maister’s framework is also developed in later work, including Ashish Nanda, Strategy and Positioning in Professional Service Firms, Harv. Bus. Sch. Case Study No, 9-904-060, 6-10 (2004).

DAVID H. MAISTER, MANAGING THE PROFESSIONAL SERVICES FIRM 4 (1993).

The idea for the contract storyline suggested to authors by Susan M. Chesler & Karen J. Sneddon, Once Upon A Transaction: Narrative Techniques and Drafting, 68 OKLA. L. REV. 263, 276 (2016).

Symposium, The Changing Role and Nature of In-house and General Counsel: Is the In-house Counsel Movement Going Global? A Preliminary Assessment of the Role of Internal Counsel in Emerging Economies, 2012 WIS. L. REV. 251, 295 (2012).

ACC EXTRAS ON… Contract management

ACC Docket

Top 10 Considerations When Implementing a Contracting Automation Tool in Asia-Pacific (Jan. 2020).

The Operational GC: Turn Your Contracts into Real, Day-to-Day Risk Mitigation (Nov. 2019).

Three Steps to Bolster Your Contract Management Process (Dec. 2018).