Banner artwork by sergomezlo / Shutterstock.com

Cheat Sheet

- Institute data disposition policies. Data retention is about more than privacy law. There are often other regulatory requirements — worldwide — as well as business needs.

- Beware of fines. Ignorance is not bliss — you could get hit with steep fines if you mishandle private data.

- Identify a team. Determine the critical business units and stakeholders who can weigh in your policy development.

- Clarify what constitutes a legitimate business need. For non-prescriptive rules such as business justification, following a documented, good-faith process demonstrates compliance and provides defensibility.

Worldwide, new and existing privacy regulations require that personal information be retained only as long as necessary for legitimate business need. To comply, organizations are developing data retention and disposition policies — which involve much more than privacy — to avoid conflicts while complying with non-privacy regulatory requirements. And more important than just a data retention policy, care and diligence practices need to be implemented and executed. In-house counsel must be aware of these issues in order to help the business implement these requirements.

Privacy requirements drive data minimization

Many jurisdictions have implemented data minimization laws: specific requirements to collect and maintain the minimum necessary personal information to achieve the business purpose.

Nearly all organizations create and retain personal information about individuals. Many organizations are business-to-consumer (B2C) and hold customer information, which these laws directly cover. However, some of the comprehensive privacy laws – the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) in the United States, and Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), to name but two – also cover the information about employees or other business-to-business (B2B) relationships. New and emerging privacy regulations restrict the retention of this personal information to “no longer than necessary” for a legitimate business need.

While many of these regulations have been active several years, retention and disposition requirements have generally not been meaningfully enforced. That, however, has been changing — quickly. In Europe, for example, companies are facing fines for keeping personal information too long.

Companies are facing fines for keeping personal information too long.

Many companies are also getting ready for California’s enforcement as its privacy rules come into effect. Furthermore, the US Federal Trade Commission has long encouraged and enforced data minimization through its recommendations and requirements. Note also that most privacy compliance regimes allow individuals to request that their information be deleted or erased. For those laws that cover employee information, employees and B2B representatives also enjoy these rights, which can exponentially increase the size and scale of risk.

Not following data retention time limits can result in hefty fines such as when the French data protection authority (CNIL) fined the economic interest group, Infogreffe, €250,000, for failure to comply with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) law requiring data be kept only for a period of time proportionate to the purpose of the processing.

Enforcement of data minimization principles is motivating companies to develop more involved oversight processes. Organizations, however, can use existing processes to appropriately manage the personal information lifecycle using the same tools as other information. What personal information to save, and for how long, should be addressed through the organization’s existing retention policies, both to demonstrate good faith efforts to comply with rules and to provide guidance to information technology (IT) departments and other groups on what they can save.

Watch out for logjams in developing data retention policies

Data retention policy making commonly stalls in many organizations.

Creating a data retention and deletion policy often gets bogged down through endless inputs and lack of consensus with multiple stakeholders. A mandate to “create a data retention policy” will likely result in a lot of meetings with very little forward movement without prior planning and a focus on the end result.

Creating a data retention and deletion policy often gets bogged down through endless inputs and lack of consensus with multiple stakeholders.

The root cause of getting stuck is that many data retention policies focus too narrowly on personal information disposition requirements that are not in sync with records retention compliance or business needs. Sometime organizations effectively “punt” on the issue by creating vague, watered-down, or ill-defined policies that may simply list hazy, non-prescriptive retention rules. These rules provide little guidance to employees about what to save and not save.

Furthermore, there is sometimes a tendency by privacy, legal, or compliance teams to “go it alone” and create a retention policy by themselves with little input or collaboration, and then hand it off to IT or business units to execute. There may be a policy, but it is unlikely it will be or can be followed, and the gap between what the organization says it will do in its policy and its lack of execution creates more risk than not having a retention policy at all.

Identify critical business units and stakeholders who can weigh in

First, therefore, identify critical business units within the organization, and then stakeholders within those business units who will be able to provide guidance and direction regarding what personal information the organization collects, and who will be empowered to make decisions regarding the appropriate retention of personal information.

In most organizations, these are different people within a business unit — usually a subject-matter expert and then also a director- or officer-level manager. The initial management buy-in must have a top-down approach to allocate the right resources and ensure that managers will allocate the necessary time commitment. These stakeholders will provide important feedback and, if appropriately armed with information about the risk that over-retention presents to the organization, will be champions for this effort throughout the company. These are the partners going forward.

Once in-house counsel identify the need to create or update a data retention and deletion policy/schedule, additional challenges remain, including things like management buy-in and balance among other strategic priorities, determining sufficiency of internal resources, and potentially budgetary constraints. Particularly in small legal departments, diverting staff from day-to-day legal needs may create business backlogs. There will be a similar stress on the IT team, which will be an integral part of the process. To the extent in-house counsel consider outside resources, note that such decisions need to fit within the company’s budgeting process. Once past these initial hurdles, in-house counsel must meet additional challenges in implementation.

Data retention policy v. records retention schedule requirements

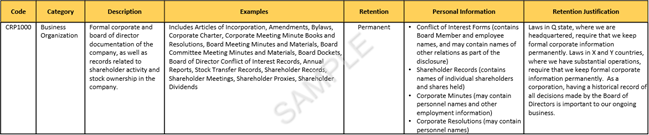

A policy is, at its core, simply a statement of what the organization does. Therefore, most organizations already have data retention policies in their records retention schedules. Policies (high-level statements) and schedules (detailed requirements) may be driven by different compliance targets, but both fundamentally seek to define what information should be saved and for how long.

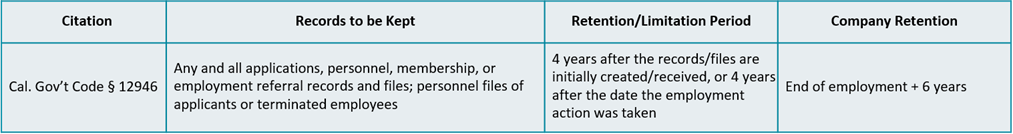

Records retention laws and regulations may require companies to retain records for a certain number of years, driven by literally thousands of record retention regulations. These requirements may override consumer deletion requests, even if the record in question contains personal information.

California’s requirement to retain employee records may create a perceived conflict with the CPRA’s requirement to retain information no longer than necessary. To resolve this, the human resources and privacy teams will have to work with the records management group and other stakeholders to identify the appropriate amount of time to retain employee records.

In many cases, including in the example above, the company’s business need for information is longer than the legally-mandated retention period – that is, the business utility of that information lasts longer than the legal utility. These examples are based on California law, but most privacy laws have similar requirements, resulting in similar potential conflicts with record retention requirements. From a practical perspective, the project team can expect to find pockets of resistance within the organization (especially for newly developed policies) defining the business need.

Data retention and disposition policies and strategies need to be synchronized with records retention requirements. Conflicts between the two can create non-compliance. As such, the most compliant, easiest, and smartest approach is to incorporate both into a single policy. Both sets of requirements aim to detail what information needs to be saved for how long. Putting them in a single document makes it easier.

Data retention and disposition policies and strategies need to be synchronized with records retention requirements.

The end result should not focus exclusively on legal and regulatory requirements. Rather, these policies also need to address business need and value. Good retention policies serve not only as legal statements, but also seek to achieve a reasonable consensus with business units and other stakeholders regarding what information needs to be maintained to run the business and what can and should be deleted (and when). Any deletion exercise depends on having this agreement. Failing to build this consensus at the beginning will force companies to revisit it every time they try and delete information.

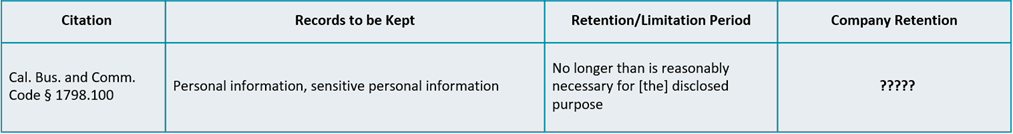

Most privacy laws require a business justification for retaining personal information. Unfortunately, there is no “bright line” rule or existing case law clearly indicating what constitutes a legitimate business need. Organizations should develop a process for determining and documenting business need. For non-prescriptive rules such as business justification, following a documented, good-faith process demonstrates compliance and provides defensibility.

Attributes for creating a schedule

Establish a privacy-enabled records retention schedule (or records-enabled data retention policy) that all departments know to follow.

Many organizations are updating their retention policies to address a larger set of requirements. To build a good, enforceable, compliant retention policy and schedule, the group’s efforts must:

- Include an inventory of all information types. A first step is identifying all the types of information across the organization. This inventory should span all media types including structured data in database systems, unstructured file content, semi-structured emails, social media, etc., as well as paper documents.

- Apply legal and regulatory retention requirements. From the larger inventory, based on the content and independent of media, determine the legal and regulatory requirements. This can include national, state/provincial, local, as well as industry-specific regulations. For organizations that operate across multiple countries, these requirements must be identified for each country. In general, where possible, create global retention categories and define local exceptions where necessary. Also consider explicitly calling out non-records.

- Determine business value. Companies can and should define retention based on business value. In other words, a company can declare something a record because it has business value even if there is no underlying regulatory requirement. Business value can include intellectual property, trade secrets, and operational needs.

- Address personal information. Identify which records and non-records contain personal information, and which privacy requirements may apply.

- Include disposition requirements. If regulations with maximum retention periods exist (for example, “Destroy after Two Years”), include these disposition requirements in your retention schedule.

- Identify legitimate business need. For retention of personal information, include a description of the legitimate business need for the retention as stated.

- Consider the need for legal holds. Companies facing or anticipating litigation or regulatory investigations have a duty to preserve that information. This duty to preserve usurps all records expiration or privacy disposition. Polices should acknowledge this responsibility.

- Obtain consensus with the business. Finally, continue to discuss the policy, business value, and retention requirements with business units and other key stakeholders, seeking to achieve reasonable retention periods.

Companies can and should define retention based on business value.

It’s worth the effort now to avoid complications later

Meeting data minimization requirements creates an additional complication on top of existing and often challenging records retention requirements. Avoid the temptation to create separate policies or to go it alone. Engage other stakeholders as well as business units. Keep the policies up to date. Developing compliant, balanced approaches in modern, easy-to-execute policies may take a little more effort at the beginning, but well-crafted policies make execution much easier, reduce downstream conflicts, and reduce or avoid disposition resistance from business units and employees. It is worth the effort to do it right.