It’s now clear that the COVID pandemic is not a short-term disruption; it has upended the “norms” of not only business operations but also how organizations must think about employee health and privacy. In-house counsel are often tasked with assisting stakeholders (or more often, on our own) with developing practices to reduce the spread of the virus to our constituents. As more government authorities are issuing health guidance that includes monitoring people in order to operate, such as temperature checks, required quarantines, contact tracing, or all of the above, in-house counsel must also consider the implications for our businesses. These requirements lead us to the intersection of technology, privacy laws, and employee (or customer) rights under those laws and how organizations use and store biometric data.

This article will provide an overview of biometric data, including how it is currently addressed under United States privacy laws. We will also provide questions and suggestions to assist other in-house counsel with advising their organizations in the new COVID-19-driven workplace.

What is biometric data?

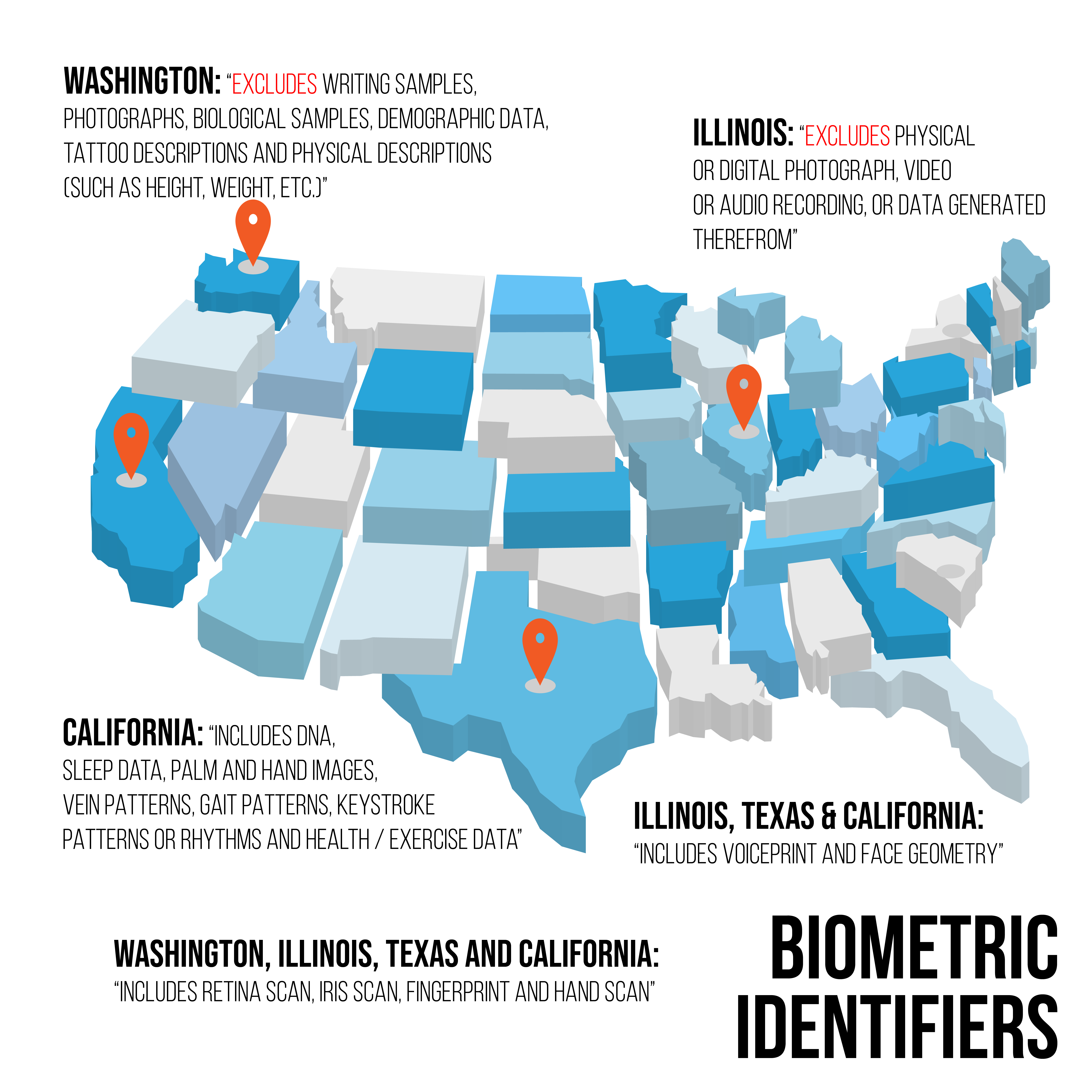

Biometric data comprises physical or mental characteristics that can identify a person. This data falls into two buckets: physiological and behavioral. When we think of biometric data, we often think of what is in the physiological bucket — fingerprints, DNA, retinal scans, facial image, etc. — all data that pertains to an individual’s body. However, behavioral data, such as patterns in keystrokes, gait, signature, and voice are also considered within the “biometric” sphere. All of these, regardless of bucket, can be used to identify a person.

How states regulate biometric data use

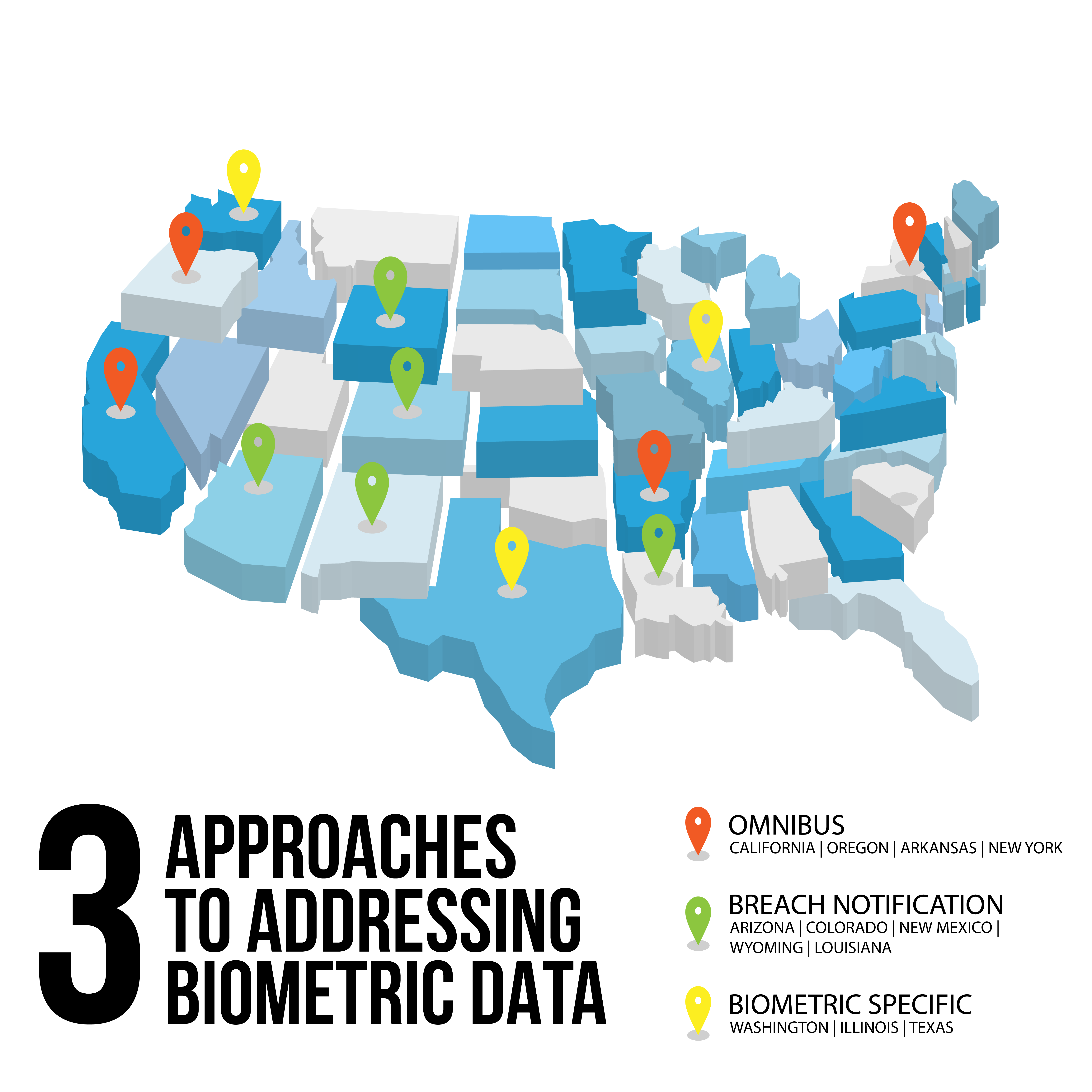

In the United States, laws governing biometric data are typically found at the state level, although some states have yet to pass laws that regulate biometric data. How these states have approached regulating biometric data varies. The approaches fall within three categories:

- The omnibus approach: including biometric data in the state’s law governing personal information;

- The biometric data specific approach: passing a law that specifically addresses biometric data, and not folding it into a general privacy law; or

- The augmented breach notification approach: adding biometric data as information that, if impacted in a data breach, could require notification to affected individuals.

Adding another layer of complexity, each state that does regulate biometric data defines it somewhat differently.

It is quite difficult to track applicable privacy laws and biometric requirements and keep up with the frequent changes, especially for companies that have operations in more than one state.

Most readers will be familiar with the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). The CCPA went into effect at the beginning of 2020 and includes biometric data in its definition of personal information. The CCPA defines biometric data very broadly to include:

“physiological, biological or behavioral characteristics, including … DNA[,] that can be used … to establish individual identity,” including “imagery of the iris, retina, fingerprint, face, hand, palm, vein patterns, and voice recordings, from which an identifier template, such as a faceprint, a minutiae template, or a voiceprint, can be extracted, and keystroke patterns or rhythms, gait patterns or rhythms, and sleep, health, or exercise data that contain identifying information.”

There are no specific requirements for the collection, use, or disclosure of biometric data under CCPA. Instead, the disclosure requirements and consumer rights provided under CCPA apply to biometric data the same way they do to other personal information held by companies of the requisite size.

The CCPA is primarily enforced by the California Attorney General. However, there is a private right of action in some circumstances: “subject to an unauthorized access and exfiltration, theft, or disclosure as a result of the business’s violation of the duty to implement and maintain reasonable security procedures.”

In addition, the California AG has recently released regulations governing the CCPA. At present the CCPA does not apply to employers and the data kept on employees or so-called “business to business” data, although this exception is scheduled to expire on January 1, 2023.

Perhaps the most well-known biometric law — and certainly the one that has led to the most litigation — is Illinois’s Biometric Information Privacy Act (or BIPA). BIPA provides that a private entity cannot collect biometric identifiers unless it provides disclosure to the subject that biometric identifiers are being collected, why they are being collected, how long the data will be retained, and whether the private entity received a written consent from the subject. BIPA also provides for a private right of action for its violation, with statutory or actual damages, as well as attorney’s fees and costs.

In January 2019, the Illinois Supreme Court in Rosenbach v. Six Flags Entertainment Corp. held that a violation of BIPA’s notice requirements was sufficient injury for an individual to have standing to sue under the statute and an individual does not need to demonstrate actual harm. Although the Illinois legislature is considering an amendment that would remove BIPA’s private right of action, it has yet to adopt any such change.

Later in 2019, the 9th Circuit held that it would follow the Illinois Supreme Court’s holding in determining that a federal plaintiff suing under BIPA would be able to allege sufficient harm to meet the Article III standards for a case or controversy. Earlier this year, the 7th Circuit made a similar holding to the 9th Circuit in a matter brought by an employee challenging her employer’s requirement that employees establish an account using their fingerprints in order to make purchases from its cashless cafeteria.

Washington and Texas are the other states that have specifically addressed biometric identifiers in their statutes. Washington’s biometric data law excludes physical or digital photographs, video or audio recordings, or data generated from such recordings. It also exempts government agencies, financial institutions covered by the Graham-Leach-Bliley Act, along with activities subject to Heath Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Washington chose to have its law enforced by its State Attorney General’s Office and not to permit individuals a private right of action.

Moreover, like most privacy statutes, notice and consent are required for the lawful collection and use of biometric data. In spring 2020, Washington also enacted a law that limits state or local law enforcement’s use of facial recognition technology. To justify its use of these tools, law enforcement agencies must demonstrate that adequate testing of facial recognition technology occurred along with requiring law enforcement to provide notice of use to its citizenry (and to any defendants where used on them).

Critically, law enforcement must obtain a warrant prior to the collection of biometric data.

Texas takes a different approach to biometric data use and oversight. Texas prohibits the capture of an individual’s biometric identifiers for a commercial purpose unless the individual has been provided with notice first and then also consents. Texas law also limits the sale or disclosure of an individual’s biometric data except under limited circumstances, which includes disclosure to the individual first.

The statute also requires organizations be able to demonstrate that they have instituted an appropriate level of security for any data collected along with a mandatory destruction period. Like Washington State, Texas’ biometric law is enforced by its State Attorney General.

Data breach notifications

Although most states do not have specific laws to address the collection and use of biometric data, many have included biometric data among the data types covered under their respective data breach notification laws. In addition, some states are expanding their requirements so that organizations also must be able to demonstrate that they have sufficient data security practices that protect the integrity and confidentiality of data in their possession or control. These requirements also include biometric data in the definition of personal information.

Hitting the moving target

With this patchwork quilt of legal requirements, what is a good way forward?

First, what are your organization’s operational requirements? Does it need to reopen offices? If so, are on-site employees necessary to continue operations? Or can employees work from home? If onsite employees are required, are all of them required at the same time? Will customers be allowed in the organization’s facilities? Is your sales team required to be at customer sites? Will sales team be permitted to travel?

Once questions like these are considered, next look to what requirements are being imposed on your organization by government bodies. Is your organization required to participate in contact tracing? Or take temperatures? If there is no guidance, what does your organization believe is the best path forward? Will you screen the temperatures of people (employees or customers) entering your facilities? If so, then how will you do this? Will you record the temperature in association with a person’s name? This is not solely for employees. For example, airports and airlines are screening passengers for temperature. This inherently associates a person with a temperature.

Next, consider how the information collected will be recorded or stored. Will temperature be checked but not recorded? Will temperatures be recorded for the day or week and then discarded? Alternatively, will temperatures be maintained in an employee’s records? These are all possibilities depending on your industry and local requirements.

Whatever your requirements, creating a policy that explains the purpose for collection and a procedure governing the process is key. The development of both items will help the organization clarify for itself why this data is needed, for how long, and how it will be collected. If possible, we recommend involving key stakeholders such as human resources, marketing, information technology, and operations as each group may have insights or questions about the process. In any event, we strongly recommend not issuing these documents in a vacuum.

Common concerns

Question: Gloves and masks interfere with the tools that our organization uses to track employees’ hours and otherwise comply with its security access system. What is the potential impact if the organization begins to utilize a lower tech system? Is it facing potential compliance issues?

Organizations faced with these types of questions may first wish to consider why the practices were instituted prior to the current situation. Usually there is a necessary reason that will need to be addressed if the process is changed. Next, consider if the organization’s data deletion policies need to be modified? Will additional data be required? What will be done with data already collected? What data is the organization going to collect and whether/how will it store the new data? Does the organization have to delete it all? That would depend on why data is being kept. Are the organization’s policies and procedures sufficient to provide adequate notice and demonstrate reasonableness? Also, consider whether state laws may affect the answer, because some states require deletion of the data when it is no longer collected.

Question: The organization has biometric data from workers who may be on leave, furloughed, or temporarily laid off. Does the organization have additional obligations?

If an organization has furloughed or laid off personnel, it has biometric data that it may no longer require for the purpose that it was collected for (e.g., employment). An organization should review its existing policy to ensure that its data is deleted consistently with policy and guidelines. Critically, data privacy issues are not the only consideration. Other state laws may require that data be kept for longer. If so, then it is important that organizations also ensure that they are following industry-appropriate practices for storage, for example using encryption, and observing required deletions schedules.

Question: The organization would like to require employees to wear devices that track their location when they are not working on premises. What issues should the organization consider?

Geolocation data is not considered biometric information under most definitions; it certainly does not fit the definition at the beginning of this article. However, California law covers geolocation data, and other states have proposed or adopted legislation that includes geolocation data in the definition of personal information. Moreover, wearable devices may collect more than geolocation information, so it is imperative that the organization understand what information is being collected and where it is going. In most cases, an organization should determine early in its process the reason why a location-tracking device is needed and what it is hoping to achieve by creating this requirement. For example, should all employees be asked to comply or only those in a critical or highly regulated area of the organization’s operations? The organization will also need to consider whether its current policies and procedures (e.g., notice, retention, deletion) address this set of facts. Is the employee handbook sufficient? Is a supplemental policy required? The organization may wish to go beyond simply notifying employees and issue an FAQ explaining the new tool, the data being collected, and what the data will be used for going forward.

Question: The organization would like to track employees’ temperatures prior to entering our office space. What do privacy laws say about this practice?

Again, while much depends on the specifics of the laws in the organization’s state, most privacy laws focus on the storage of data. If the organization’s plan is to take each employee’s temperature for screening purposes (e.g., digital thermometer swipe), it could obtain an individual’s consent and not store data. This practice should be in compliance with privacy laws. However, some thermal devices also collect identifying information, such as facial geometry, or other employee specific information in conjunction with the temperature. If facial geometry information is being collected, the organization should also ensure that it is complying with applicable biometric privacy laws. Because temperature is a health-related piece of information, the organization may also be required to comply with laws governing privacy and security of health information.

6 suggestions for the way forward

As states “re-open” (or “re-close”) their economies, organizations (and their counsel) face truly unprecedented challenges that will impact the way they will operate going forward. Below are suggested practices to consider during this process:

- When considering a new practice, procedure, or data collection point, determine the justification for doing so and challenge that justification. For example, is the data to be collected necessary to meet a statutory requirement or is it an attempt by management to monitor workers? Is there a less intrusive option? If so, and it is not used, document management’s reasoning.

- Determine whether current security protocols are adequate. If not, either delay collection until adequate security controls are in place or document and implement a remediation process.

- Determine whether notice, policies, and procedures meet minimum requirements.

- Determine whether consent for collection and storage of biometric data is required under applicable law. Also consider whether consent must be obtained at every collection.

- Take steps to ensure that only parties who require access to data will have access.

- Is the organization using a vendor to store this data? If so, does the vendor have adequate safeguards in place to protect this data? Does this vendor sell or otherwise disclose the data for a purpose other than it was permitted by the organization?