Even without invoking Latin, lawyers have a fount of uncommon phrases to baffle our clients, ranging from the rule against perpetuities and attractive nuisances to the statute of frauds and usufructuary interests. Fortunately, few of these terms of art appear in the agreements that in-house counsel need to explain to clients on a daily basis.

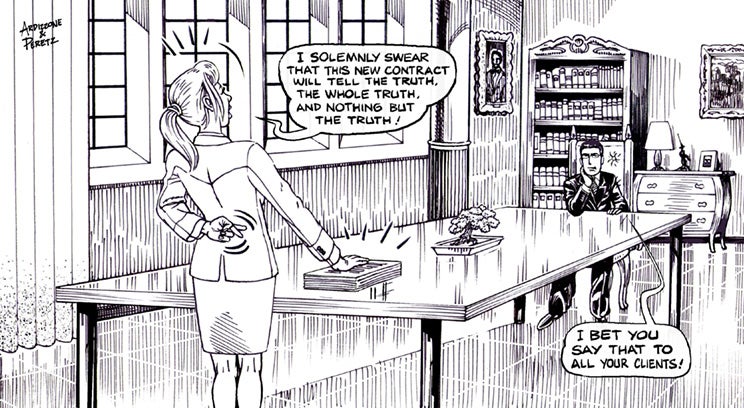

By contrast, you cannot run away from the integration clause if you’re an in-house attorney, and it is likely equally baffling to your clients. Laypeople often wonder why we should care about a clause that seems to state: “This Agreement is the agreement.” Isn’t that another example of lawyers restating the obvious?

As in-house counsel, we need to educate our clients that the presence or absence of an integration clause can have significant impacts on our business operations.

Aren’t integration clauses something we covered in calculus?

Indeed an integration clause (sometimes called a merger clause) is an important part of the calculus in developing a contract to document the relationship between two or more parties. The integration clause typically states that the agreement represents the complete and final agreement between the parties, and it supersedes any other agreements between the parties on the subject matter covered by the agreement.

Integration clauses are intended to facilitate a court (or other finder of fact) to interpret a contract to limit the evidence of the terms of the agreement to the four corners of the contract itself. One California court put it succinctly: “The purpose of an integration clause is to preclude the introduction of evidence which varies or contradicts the terms of the written instruments.”

A typical integration clause may look like this:

Except as specifically stated otherwise herein, this Agreement sets forth the entire understanding of the parties relating to the subject matter hereof, and all prior understandings, written or oral, are superseded by this Agreement. This Agreement may not be modified, amended, waived, or supplemented except as provided herein.

That sounds familiar. So familiar that we don’t give a second thought, like the train running outside the Blues Brothers’ apartment window:

Jake: How often does the train go by?

Elwood: So often that you won't even notice it.

Because it appears so frequently, in-house counsel and their clients often don’t consider when it might be inappropriate to include such a clause in agreement — or realize that an integration clause is missing.

Beware the hypnotic boilerplate

An important role for in-house counsel is supporting the procurement of supplies and services for your company. Unless your organization has significant buying power, such as the hiring of an individual contractor, the seller typically provides the first draft of the contract that will be used. You need to examine supplier agreements closely and ferret out any integration clauses that your clients ignore as “boilerplate.”

Before signing off an agreement with an integration clause, it’s time to scrutinize the deliverables promised by the supplier. Ask your client:

- Is the list of deliverables complete?

- Is it sufficiently detailed to ensure that the correct goods or services will be delivered?

- Are there acceptance criteria or standards applicable to the deliverables?

- Were there promises by the salesperson that are not documented in the agreement itself?

The presence of an integration clause without an adequate description of the deliverables opens the door for a supplier to over-promise during the sales phase and under-deliver during the execution phase of the agreement without many consequences.

It will be harder for you to argue that you should have received certain goods and services described in the sales process if they are not specified in the final agreement and both sides agree that the contract represents the entire agreement between the parties. One way to reduce this risk is to insist that sales and marketing materials of the supplier be incorporated as exhibits in the underlying agreement.

If the integration clause is contained in one of your own agreements with a client, you need to educate your operations and customer success team members about the presence of the clause and what it means. These team members are your frontline in handling clients’ requests, which may include demands beyond the scope of your agreement with the client.

Team members who interact with the client should have ready access to the client agreement and be able to explain to the client that the sum total of what was promised to the client is contained in the agreement. Clients generally also appreciate a pointer back to the signed agreement between the parties, rather than sorting through imperfect memories of past conversations.

If you need to address any client dissatisfaction with the terms of the contract, work with your customer success and operations team to help them document any proposed amendment to the agreement, which may integrate some aspects of the original agreement, while changing other aspects of it.

Shields up

Consider your organization’s longer term relationships, such as those with employees. It’s time to review those to determine which ones might be missing an integration clause. You might think an agreement with a key manager is up-to-date if it is reflected in an letter; however, this may be insufficient to overcome prior promises and oral communications to the employee if an integration clause is missing.

A tax preparation company discovered this when it sought to terminate a manager based on certain articles of employment that lacked “words of integration.” The company was unable to permit the employee’s introduction of contrary evidence, such as statements by the company that:

“We have never terminated a contract. We do not terminate contracts. Anybody who does a good job in the area will never be terminated. We do not change contracts.”

The court found the lack of an integration clause crucial in its determination that those prior statements were not superseded by the subsequent Articles of Employment. By contrast, proper use of an integration clause can effectively cancel negate the terms of a prior agreement.

A bank learned this the hard way when it updated a collateral agreement with a borrower and forgot to reference certain prior collateral in the new security agreement. The court found that, as a matter of law, prior security interests were superseded and replaced in their entirety by the new, more lax, security agreement that contained an integration clause.

Perhaps you are not sure when your organization will be able to deliver the products promised, but your salesperson has suggested potential completion dates to the client? It’s time to include an integration clause in your agreement with the client and be sure to not specify a particular delivery date.

The US First Circuit found that mere promises of delivering interoperable software by a particular date were not binding when the parties failed to include the date in agreement that contained an integration clause.

What would Harry Houdini, Esq. do?

What do we do if we belatedly discover an integration clause that hinders the court from a complete understanding of the agreement between the parties? How do we escape? The first question to ask is: Who wrote the contract? And did our side have any bargaining power? Courts such as the federal court in Delaware have given greater deference to integration clauses presented in a “formal written contract between sophisticated parties[.]”

By contrast, if there is an argument that your side was a less sophisticated party (at the time of contract signing) and the integration clause was contained in a contract of adhesion, you may have a better shot at arguing a lack of mutual understanding that the contract truly represented a shared belief that the contract contained the entire agreement between the parties.

Consider whether there has been a change to the contract after it was signed. While parol evidence may hinder the introduction of evidence that pre-existed execution of the agreement, there may be an opportunity to argue that a contract has been altered after execution or whether the contract itself makes reference to external documents that could have been legitimately altered or updated after execution of the agreement.

For example, an insurer in New York used this line of argument to convince a federal court to admit updated data sheets that were created after a contract had already been executed, despite an integration clause in the original agreement.

Muster your contemporaneous notes about contradictory promises that run contrary to the written agreement containing the integration clause. In California and many other states, courts may consider the language and completeness of the written agreement, whether the terms of any alleged oral agreement contradict those in writing, and whether the oral agreement might naturally be made as a separate agreement. A written agreement that is clearly incomplete might open the door for the introduction of additional evidence about the parties’ intentions beyond its four corners.

The unknown unknowns

Despite the presence of an integration clause, parol evidence may be introduced to prove fraud even if inconsistent with the terms of the contract. This is because, when fraud is present, it cannot be demonstrated that the parties had a meeting of the minds when entering into the agreement.

Thus, if the reason you want to introduce extrinsic evidence into a contract dispute where you are barred from doing so by an integration clause, consider whether there was a misrepresentation that influenced your party to sign the underlying agreement.

Statements that induced you to enter into the agreement that later proved to be fraudulent may serve as sufficient reason for the court to disregard an integration clause. For example, the presence of an integration clause in a chemical company’s contract was insufficient to bar litigation about alleged fraud based on, inter alia, product safety misrepresentations.

Another area where you may find pre-contractual fraud sufficient to override an integration clause is an examination of the actual expenses compared to those promised prior to signing the agreement. Some courts have held that a party who knew or should have known future expenses may have committed fraud if those expenses are understated during contract negotiations.

When making such a fraud allegation, remember that you need to demonstrate “more than proof of an unkept promise or mere failure of performance," and show “justifiable reliance on defendants' misrepresentation." Moreover, your reliance has to be reasonable and “cannot be established when a party simply fails to read an unambiguously-worded agreement.”

Take the lead

The next time you see an integration clause float by on your own templates or a counterparty’s agreements, it’s time to stop treating it as boilerplate. Ask your internal clients if the contract truly represents the entire understanding between your organization and the counterparty. And revisit your own agreements to explore where a timely placed integration clause could protect you down the road from prior agreements and meandering sales promises.