CHEAT SHEET

- Why? Parties should first ask why they should include an indemnification provision and what goals they hope to achieve. This will guide the drafting process.

- Who? Once goals are determined, the next step is identifying what roles each party with play (indemnitor, indemnitee, or both) and who the provision is protecting.

- What? Narrow down what the possible harms, losses, and liabilities are, and what the extent of the indemnification will be.

- When and where? Indicate when the right to indemnification arises and when payment may be sought. Also be aware of which jurisdiction will govern the contract.

Indemnification provisions are commonplace in many energy industry contracts. Yet commonplace does not equate to simple or uniform. In fact, indemnification provisions often warrant a great deal of scrutiny.

The triggering of an indemnification provision can be a very costly endeavor. Additionally, though the basic idea of shifting the risk of loss or liability seems straightforward, indemnification provisions are more complex than they may initially appear. Anticipating how an indemnification provision might be triggered and how its language may be interpreted is vital.

Given its importance and complexity, great care must be taken when drafting an indemnification provision. Parties should consider the five W’s and one H — who, what, when, where, why, and how — as they draft indemnification provisions in energy contracts.

In the simplest of terms, the indemnitee is the party who will receive payment or the benefit of payment if the indemnification provision is triggered. The indemnitor is the party who must make that payment.

Who

Who are the indemnitee and indemnitor?

The most basic “who” consideration in drafting an indemnification provision is identifying the roles of the parties to the contract. The drafter must identify who will be the indemnitee and who will be the indemnitor. In the simplest of terms, the indemnitee is the party who will receive payment or the benefit of payment if the indemnification provision is triggered. The indemnitor is the party who must make that payment.

The roles of indemnitee and indemnitor will not necessarily be static. Indemnification provisions can be written so that, depending on the circumstances, a party may occupy either role. If the parties might be sued by the same type of third-party or face similar types of claims, the indemnification provision can be written to provide reciprocal protection for each party. In this instance, the role each party takes on will likely hinge on who is considered to be at fault for the harm done. In essence, each party will take responsibility for the harms it causes by indemnifying the other party for damages or losses resulting therefrom.

Identifying a corporate entity as the indemnitee or indemnitor should also involve specifying the persons or groups of people who are treated as a part of that entity for purposes of indemnification. Depending on the circumstances, the parties may wish to broaden or clarify the provision to ensure that it covers the entity’s officers or employees. The provision could even be written to cover agents or third parties related to the contract or its subject matter.

Who can initiate a suit or claim?

The parties also need to identify “who” may initiate a suit or make a claim as a result of the parties carrying out the aims of the contract. An indemnification provision is likely to come into play if one of the parties is or may be liable to a third party, such as employees, contractors or sub-contractors, landowners, customers, or visitors. It might also be governmental agencies if performance of the contract might lead to claims of environmental damage or other regulatory violations. The “who” in this instance may also be one of the parties themselves. This occurs when the indemnification provision is written to cover expenses, losses, or damages incurred by the indemnitee that arise out of contract performance.

Once the parties have considered who might bring a claim, they need to determine what they want the indemnification provision to cover. The parties may choose to draft the provision broadly, applying indemnification to any person or entity with standing to bring the kind of claim described therein. Alternatively, they could specifically identify a person, entity, or group of people whose claims will trigger the provision’s application.

Who will the provision indemnify against?

A third “who” consideration is whose actions or omissions will the provision indemnify against. In many cases, the indemnitee is simply protected against claims brought against it as a result of an action or omission of the indemnitor. Additionally, the provision may cover actions of third parties, especially those who are outside of the indemnitee’s control but may be within the indemnitor’s control. Under certain circumstances, an indemnification provision may also be written so that the indemnitee will be indemnified from claims arising out of the indemnitee’s actions or omissions. However, most courts will require that the indemnification provision’s language be clear and unequivocal if the parties intended it to protect the indemnitee from its own actions.

What

What is the indemnitor indemnifying against?

Determining whose actions or omissions will trigger the indemnification provision leads directly into the first “what” consideration for drafting — what will the indemnitor be indemnifying against? It is impractical, if not impossible, to attempt to individually list all the scenarios that could lead to a lawsuit. Therefore, the parties will likely need to look at this question in broader terms.

What are the potential harms?

To start, the parties should consider what types of harms could result from performance of the contract. These harms could include personal injury, property damage, environmental or other regulatory fines, etc. This part of the process requires the parties to take a “what if” approach. They can assume for purposes of this exercise, that everything that could go wrong will go wrong.

The parties should be aware that using both general language and more specific language could result in the provision being read more narrowly.

The parties should also consider what could be the cause of these harms. Could personal injury or property damage be caused by the negligence of one of the parties? Could a party’s actions or omissions give rise to a strict liability claim? If a party’s performance of the contract fails to meet standards set out by an agency or other governmental entity, could that result in a fine or even a project-delaying injunction?

What are the potential damages or losses?

The parties should then consider what kinds of damages or losses could result. This will likely include direct damages, but the indemnification provision should also address whether it will cover consequential damages, punitive damages, or fines. With respect to punitive damages, the parties are best served by expressly indicating whether or not punitive damages are covered. However, certain expansive language such as “without limitations” may be sufficient to include punitive damages. The parties should also consider whether the provision will cover attorney fees and related costs.

Once the parties have developed a universe of potential “what ifs” and expensive outcomes, they should decide which of these they want the indemnification provision to cover. They could draft the provision in a very broad way to cover all sorts of damages and losses, regardless of the type of harm incurred or what caused that harm. Alternatively, the parties could draft a narrow provision to protect the indemnitee from limited damages or losses caused only by certain causes.

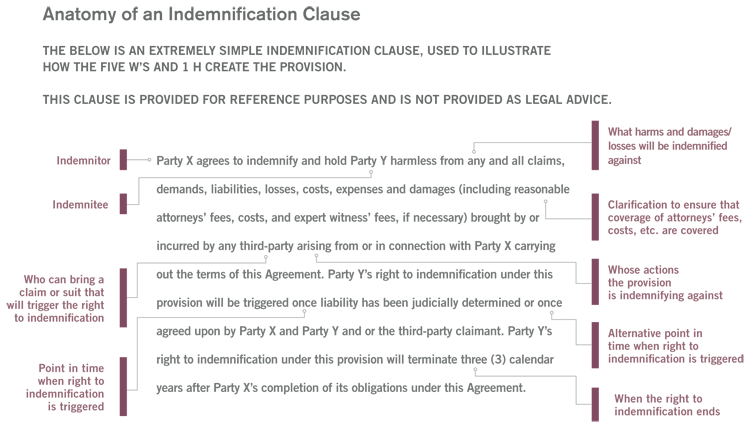

Anatomy of an Indemnification Clause

THE BELOW IS AN EXTREMELY SIMPLE INDEMNIFICATION CLAUSE, USED TO ILLUSTRATE

HOW THE FIVE W’S AND 1 H CREATE THE PROVISION.

THIS CLAUSE IS PROVIDED FOR REFERENCE PURPOSES AND IS NOT PROVIDED AS LEGAL ADVICE.

The parties should be aware that using both general language and more specific language could result in the provision being read more narrowly. In Interstate Power Co. v. Kansas City Power Light Co., the indemnitee raised the defense of indemnification when the indemnitor sought contribution from the indemnitee under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA). The court was tasked with determining whether indemnification provisions in various contracts between the parties were sufficient to negate CERCLA’s right to contribution.

Two of the indemnity provisions at issue contained broad language purporting to indemnify “against all liabilities and obligations of every kind and character whatsoever.” However, the court pointed out that those provisions went on to describe more specific liabilities and obligations. Ultimately, the court held that these specific references negated the effect of the broader language and the indemnification provisions could not be read to include indemnification against contribution under CERCLA.

When

When is the indemnification provision triggered?

The first “when” that the parties should consider, is when will the indemnification provision be triggered. Admittedly, this consideration might also be phrased as a “what” question — what type of indemnification is being provided? Is it indemnification against liability or loss?

If the clause envisions indemnification against loss, the indemnitee must pay out damages or costs before it can attempt to recoup that money from the indemnitor. If a personal injury suit is filed against the indemnitee, the indemnitee will not be entitled to payment from the indemnitor unless and until the indemnitee pays out damages related to a third-party claim against it or otherwise incurs an actual loss that is covered by the provision.

If the provision provides for indemnification against liability, the right to indemnification is triggered when liability is determined. This is true even if a judgment has not yet been paid by the indemnitee. This can be useful if the indemnitee does not have the cash flow to pay the damages up front and then seek reimbursement later.

When does the right to indemnification end?

Too often, another important “when” consideration is left out of indemnification provisions completely. That is — when does the right to indemnification end? Depending on the subject matter of the contract, it may be logical for the right of indemnification to terminate once the aims of the contract are complete. However, for some contracts, issues or claims may not arise for quite some time after completion.

If an attempt is made to enforce the right to indemnification, and one party argues that such right has terminated, the court will analyze the contract to determine the intent of the parties. If the contract clearly specifies when the right terminates, the court’s job is simple. Otherwise, the court will examine other contract language and evidence to determine intent.

As with all contract provisions, drafters of indemnification provisions must pay attention to the jurisdiction, which will dictate the interpretation of the contract. Knowledge of statutory and case law regarding indemnification provisions in the jurisdiction is valuable information.

In a 2005 case, for example, the indemnitor argued in a motion for summary judgment that performance of the contract was completed years before the alleged loss was incurred, and that it was no longer required to indemnify against such a loss. However, the court pointed out that the indemnification provision did not specifically limit the time frame for indemnification. Before remanding the case, the court stated that the clause at issue provided indemnification for any losses that arose from the contract or were connected therewith. Therefore, regardless of timing, a loss that could be tied to the contract would be covered by the indemnification provision.

To avoid the concern for never-ending indemnification, the parties may wish to come to an agreement on what is a reasonable time period given their relative positions and the subject matter of the contract. Then, that period can be clearly stated in the indemnification provision in order to avoid future confusion or disagreement. This part of the indemnification provision should also indicate if the right to indemnification automatically terminates at the end of the stated period, or if the parties must do something to formally terminate it.

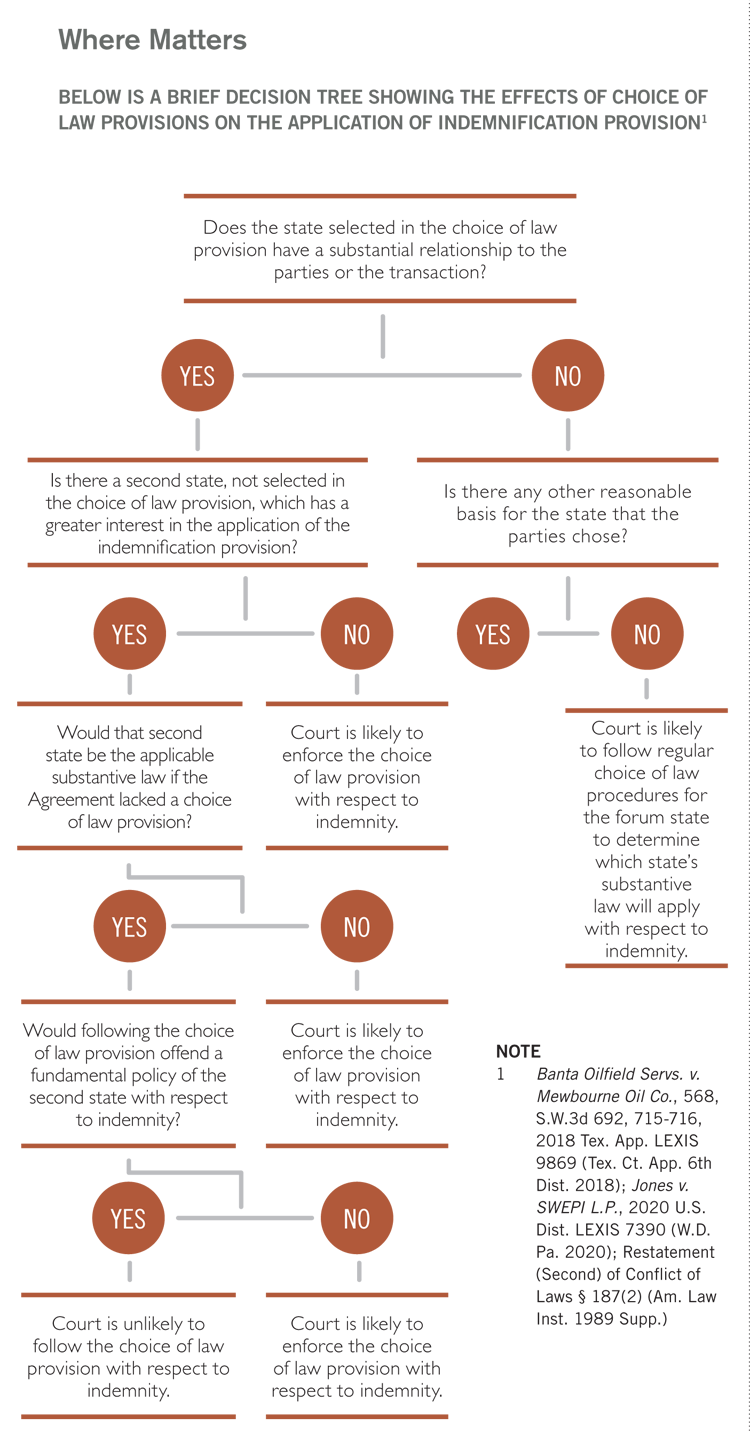

Where Matters

BELOW IS A BRIEF DECISION TREE SHOWING THE EFFECTS OF CHOICE OF LAW PROVISIONS ON THE APPLICATION OF INDEMNIFICATION PROVISION1

Where

Where will the indemnification provision be interpreted?

As with all contract provisions, drafters of indemnification provisions must pay attention to the jurisdiction, which will dictate the interpretation of the contract. Knowledge of statutory and case law regarding indemnification provisions in the jurisdiction is valuable information. The answer to this “where” question could have unintended consequences on whether the indemnification provision will be enforced the way the parties originally intended.

Where are there anti-indemnification statutes?

Multiple US states have anti-indemnification statutes that may prevent an indemnification provision from being enforced. For example, the Louisiana Supreme Court has indicated that the purpose of the Louisiana Oilfield Anti-Indemnification Act (LOAIA) “is to protect certain contractors, namely those in oilfields, from being forced through indemnity provisions to bear the risk of their principals’ negligence.” Provisions like these are premised on the idea that a party ensured indemnity for their misdeeds is more likely to act carelessly.

While some of these statutes broadly apply to all industries, some specifically apply to dangerous activities or even specific parts of the energy industry, like drilling or mining. Drafters should not rely solely on their interpretation of these laws, however, as even the narrower statutes are sometimes read more broadly. Though LOAIA specifically deals with oil well operations, a court held that LOAIA prevented enforcement of the indemnification provision of a catering contract where performance of the contract took place on a production platform and was considered to be sufficiently related to well operations to fall within the purview of the statute.

Even in instances where anti-indemnification provisions do not apply, many jurisdictions apply strict standards to indemnification provisions where the indemnitee will be indemnified for its actions or omissions. As mentioned above, the typical standard in these jurisdictions is that the language of the indemnification provision must clearly and unequivocally demonstrate that the parties intended such a result. In some jurisdictions, even a broad statement that the indemnification will take place regardless of the party at fault is insufficient to protect an indemnitee from the costs of its own negligence.

Determining the “why” can also help the parties to decide if there are other provisions that they should include in the contract and how those clauses should interact with indemnification.

Parties should consider using a choice of law provision in their contracts. These choice of law provisions may be used to increase the chances that the indemnification provision the parties use in the contract will be enforced in a predictable manner. However, the parties should also be aware that selecting a favored jurisdiction may be insufficient if they are unable to show a connection with the jurisdiction. Such a selection may also be insufficient if there exists a second jurisdiction with a greater connection to the parties and the contract where the public policy of that second jurisdiction would be violated if the choice of law provision was followed.

Why

Even though “why” is often listed last in the five W’s, parties should consider it earlier on in the process. Determining why the parties want an indemnification provision will help outline the goals that they want the provision to meet. This will guide the drafting process.

Why include an indemnification provision?

Imagine the parties want to create an indemnification provision to incentivize one party to act in a manner that will reduce the likelihood of claims or suits against either party. Perhaps they also want to protect the party who is less likely to be responsible for creating circumstances that would lead to such a claim or suit. In this instance, they can draft the indemnification provision to protect this party and simultaneously encourage the other party to act cautiously.

Determining the “why” can also help the parties to decide if there are other provisions that they should include in the contract and how those clauses should interact with indemnification. One example is the choice of law provision, mentioned above. Another example is insurance requirements for one or both parties. Reviewing the roles of the parties may also help determine who must carry the insurance, who and what should be covered by it, and what other policy requirements may apply. Additionally, the parties may decide they want to add language to task the indemnitor with defending against claims in addition to indemnifying against them.

How

Once the parties understand the questions that go into drafting indemnification provisions, they still need to figure out how to get it done. The various considerations set out above lend themselves quite well to an approach to drafting that goes from broad to narrow.

How can parties successfully draft an indemnification provision?

First, the parties should determine why they want an indemnification provision and what are the goals they are trying to achieve. This will segue nicely into determining who they are trying to protect and the role or roles each party will play.

Then, they can narrow down all the possible types of harm and who could potentially bring claims or suits. Among other reasoning, this narrowing process may be guided by what types of claims are most likely, or which are most expensive. Once they have determined which party or parties will be the indemnitee and what types of losses or liabilities they will be indemnified against, they can also determine what the extent of the indemnification will be. Will it only apply to actual damages or losses, or will it also apply to punitive damages, attorney fees, costs, etc.?

Additionally, keeping their goals in mind will also help the parties to craft language indicating when the right to indemnification arises and when payment or reimbursement may be sought. Finally, those goals will also help them determine whether the contract will specify a time period after which the right to indemnification will cease.

During the drafting process, the parties should also be aware of which jurisdiction will govern the interpretation of the contract and whether their indemnification provision will be interpreted how they intend. They should determine if a choice of law provision is needed, what jurisdiction they should select, and ensure that their choice of law provision itself will be enforceable under that jurisdiction’s statutory and case law. Their goals and analysis of the various considerations may also guide them to make decisions about including other provisions or requirements.

There are, of course, many other questions that can and should be considered in drafting. However, these 5 W’s and one H will get parties started on the right path.

ACC EXTRAS ON… Indemnification

ACC Docket

Your Vendor, Your Risk (Oct. 2019).

Ground Satellite Litigation: IP Indemnification Provisions Implicating Multiple Suppliers (Sept. 2016).

Program Materials

Boilerplate for Boilermakers: Fundamentals of Energy Project Contracting (Oct. 2015).

ACC HAS MORE MATERIAL ON THIS SUBJECT ON OUR WEBSITE. VISIT WWW.ACC.COM, WHERE YOU CAN BROWSE OUR RESOURCES BY PRACTICE AREA OR SEARCH BY KEYWORD.

References

Lone Mt. Processing, Inc. v. Bowser-Moner, Inc., 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 16430, *42-44 (W.D. Va. 2005).

See, e.g., Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Murphy Exploration & Prod. Co., 356 Ark. 324, 151 S.W.3d 306 (Ark. 2004).

See, e.g., Aymond v. Texaco, Inc., 554 F.2d 206, 209 (5th Cir. Ct. App. 1977).

See, e.g., Cottman Ave. PRP Grp. V. AMEC Foster Wheeler Envtl. Infrastructure Inc., 439 F. Supp. 3d 407, 434, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 25613 (E.D.Pa. 2020).

Nicor Gas Co. v. Wilmette, 379 Ill. App. 3d 925, 884 N.E.2d 816 (Ill. App. Ct. 1st Dist. 2008); Chevron, 356 Ark. 324, 334-335.

Banta Oilfield Servs. v. Mewbourne Oil Co., 568 S.W.3d 692, 715-716, 2018 Tex. App. LEXIS 9869 (Tex. Ct. App. 6th Dist. 2018).

909 F.Supp. 1241, 1262, 1265-1266, 1993 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 21002 (N.D. Ia. 1993).

Lone Mt. Processing, Inc., 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 16340, *32-33.

Rodrigue v. LeGros, 563 So.2d 248, 254, 1990 La. LEXIS 1380 (La. 1990)

Broussard v. Conoco, Inc., 959 F.2d 42, 1992 U.S. App. LEXIS 7411 (Ct. App. 5th Cir. 1992).

Nicor Gas Co., 379 Ill. App. 3d 925.

Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Murphy Exploration & Prod. Co., 356 Ark. 324, 334-335, 151 S.W.3d 306 (Ark. 2004).

Banta Oilfield Servs. v. Mewbourne Oil Co., 568 S.W.3d 692, 710, 2018 Tex. App. LEXIS 9869 (TX Ct. App. 6th Dist. 2018).

Jones v. SWEPI L.P., 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7390 (W.D. Pa. 2020).